Summer 2018

I Never Scream

The quiet poems and powerful legacy of Pinkie Gordon Lane

Published: October 22, 2018

Last Updated: April 1, 2019

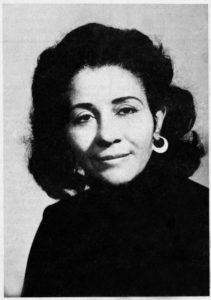

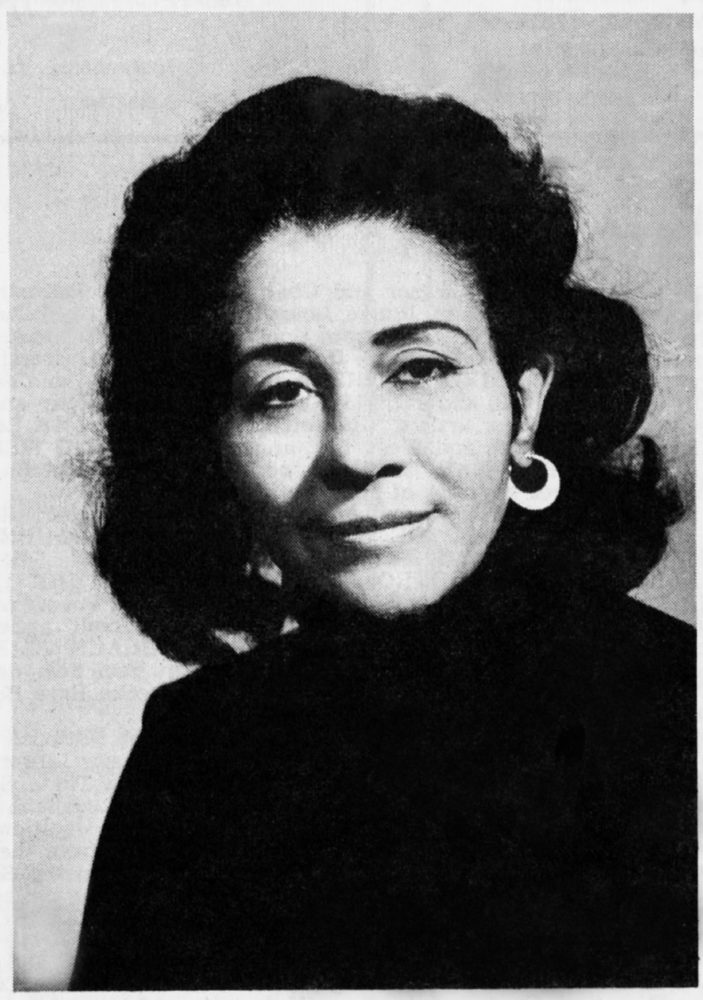

Courtesy of The Amistad Research Center.

Pinkie Gordon Lane, from The Pinkie Gordon Lane Papers.

No hands.

Then I asked, “How many of you have ever heard of Pinkie Gordon Lane?”

No hands.

I stumbled upon Pinkie Gordon Lane’s work about nine years prior to my talk at Dillard. I bumped into a fellow poet at a cafe, and we began discussing poetry. He asserted, “I just don’t understand book-type poets. You don’t need to publish. You just need to spit”—a verb used to describe poetry performance.

He went on to attribute sonnets and formal poetry to white people or nerdy black folks that he felt were worth ignoring. And he swore he could write a better poem than the one Nia Long recited in the movie Love Jones. At this point, I doubted his arrogance would allow it. I decided that day to find out who wrote the poem from the movie.

Pinkie Gordon Lane.

Pinkie Gordon, born in 1923 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was the only one of William Alexander Gordon and Inez Addie West Gordon’s four children to survive childbirth. Loneliness would later be a thread connecting many of her poems. Her parents had survived The Great Depression, and they intended to make sure she would flourish by providing the young colored girl with a prime education at the distinguished Philadelphia School for Girls. By the time she graduated in 1940, though, both her parents had died. After a brief stint as a seamstress, she sold her family’s home and applied to Spelman College in Atlanta.To be a Spelman woman is to be one of a prestigious sisterhood of black scholars, artists, and professionals. Pinkie Gordon enrolled at Spelman in 1945 and graduated magna cum laude in 1949 with a bachelor’s degree in English and Art. In 1956, she earned her master’s degree from Atlanta University. She’d recently met and married the love of her life, Ulysses Simpson Lane, and in 1957 the couple moved to Baton Rouge so he could start his new job teaching at a college in Baker.

The new Mrs. Lane did not let her role as wife and new job curb her ambition; she was on course to make history. By the 1960s, she was working as an English instructor at Southern University and pursuing a PhD across town at Louisiana State University. In 1967, she became the first African-American woman to earn a PhD from LSU, four years after giving birth to her only child, Gordon.

While Working Towards the Ph.D. Degree

Telephone unanswered, parties unserved,

Husband languishing, flat, unnerved,

Friendships neglected, kisses left cold,

Laughter—too much, too sudden, too bold.

Tears—much too quickly, as quickly forgot,

A child loved and wanted, but with prudence ungot

Dust on the table, a kitten unmilked.

Love but indulged, flowing loosely like silk.

Ethereally lost in the cold world of print,

A drunken desire, incontinent,

Ideas my only reality,

A slave in pursuit of that damned Ph.D.

(Pinkie Gordon Lane, Wind Thoughts, 1972)

While Lane was enjoying professional success as a professor and as Southern University’s first woman Chair of the English department, her husband’s health was deteriorating. He died in 1970. Lane forged ahead for the majority of her esteemed career as a widow and single parent.

While at Southern, she and Charles Rowell—the noted founder of Callaloo literary journal—would help shape the course of contemporary black poetics. After the sudden death of Melvin Butler, founder of the Southern University Black Poetry Festival, Lane and Rowell took on responsibility for coordinating the festival, which went on to become nationally acclaimed. At Lane’s urging, the festival was later renamed the Melvin Butler Poetry Festival in honor of the founder, who had also preceded Lane as chair of the department and had supported her professional development.

The festival allowed black writers to explore and celebrate their culture, hone their craft, learn about the industry of publishing, and connect to an accomplished community of writers. It was a prime incubator for nourishing black talent, also including artists working within jazz, visual art, and theatre.

In 1974, Lucille Clifton and Audre Lorde were among the black poets featured. In 1975, Mari Evans, Jayne Cortez, Sonia Sanchez, Quincy Troupe, and Michael Harper participated. Hoyt Fuller, who had been the editor of Negro Digest, gave the keynote address. In 1977, eleven years before winning a Pulitzer, Toni Morrison gave the keynote address, telling a packed room that “there is a difference between the narrow, parochial, and the intimate.” Retired Tougaloo and Dillard University professor Dr. Jerry Ward described the festival as “destination: blackness.”

Despite Lane’s expertise in festival programming, she faced criticism from peers and the faculty she supervised about her poetry not being black enough. The Black Arts Movement was ascendant, and some felt she was not reflecting urgent and relevant black themes in her poetry. In a 1990 interview with Danella P. Hero for Louisiana Literature, Lane recalled confiding in the poet, editor, and activist Margaret Danner about the criticism: “I am getting a lot of rejection from these people who say I should be writing about Black issues and ‘throw your Molotov cocktail at whitey’ and all this kind of thing, but that’s not the kind of poetry I write. [Danner] said, ‘You go right on being yourself. We all have to develop our own audience.’ I needed to hear that.”

“Pinkie didn’t want to be known as a black poet, but simply as a poet,” explained Margaret Ambrose, a friend and colleague in the English department at Southern. “It was important to her that she write about her racial experiences and beyond it. She wanted to reach a universal audience, and her poems did reach across racial lines at the time.”

A Quiet Poem

This is a quiet poem

Black people don’t write

many quiet poems

because what we feel

is not a quiet hurt.

And a not quiet hurt

does not call for muted tones.

But I will write a poem

about this evening

full of the sounds

of small animals, some fluttering

in thick leaves, a smear

of color here and there—

about the whispers of darkness

a gray wilderness of light

descending, touching

breathing

I will write a quiet poem

(Pinkie Gordon Lane, excerpted from I Never Scream: New and Selected Poems, 1985)

While some considered Pinkie Gordon Lane’s poetry not black enough or not hip to the times, Dudley Randall of Broadside Press once described Lane’s work as “another kind of black poetry.” Maybe writing the quieter poems was a form of self-care. Maybe Lane was too exhausted to scream. It is important to remember her contributions beyond the page. By all accounts, it was Lane who sustained a national black festival uplifting radical black voices for nine years while teaching, mentoring, writing, traveling, and raising a son. She may not have been writing about a revolution, but she was helping to build one.

The trick is to avoid

smashing into myself

(Pinkie Gordon Lane, excerpt of “Kaleidoscope: Leaving Baton Rouge,” from Girl at the Window, 1991)

In 1990, she took issue with an article in The Baton Rouge Advocate written by Rod Dreher, who is now a nationally popular conservative writer. Although Dreher interviewed Lane on the phone for his piece, titled “Writers find Baton Rouge a good place to live and write,” he ultimately chose not to profile her or any other black writer. “We (black poets) are also Baton Rouge writers. Or don’t we count?” she concluded in a letter addressed to him and delivered to the newspaper’s office. In addition to fighting racism, Lane also made it a point to fight misogyny, and her navigation of race and gender power dynamics in the South places her at the intersection of today’s national dialogue about women’s rights, femininity, motherhood, empowerment, and equity. Lane provides a particular lens of the black woman’s experiences through her poetry.

In a 2005 interview with John Lowe for African American Review, Lane recounts,

“…there’s one faculty member there [at Southern University], I think he still hates me, a white man I had problems with. And I asked a friend of his who was also white, ‘Why does so-and-so seem to dislike me so much?’ He said, ‘Well, have you ever thought about the fact that you are a woman, and he’s not used to being bossed by a woman?’”

Lane never gained the readership of her contemporaries—the “throw your Molotov cocktail at whitey” poets. Nevertheless, she was widely published in journals and anthologies, and she published five books of poetry: Wind Thoughts (1972), The Mystic Female (1978), I Never Scream: New and Selected Poems (1985), Girl at the Window (1991), and Elegy for Etheridge (2000). And she was honored. The Mystic Female was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. She was appointed Poet Laureate of Louisiana by Governor Buddy Roemer in 1989 and served in that role until 1992. As Louisiana’s first African-American poet laureate she represented the state for the 1996 Olympic torch relay. World-renowned music director and conductor Dinos Constantinides scored classical compositions called Listenings and Silences based on Lane’s poems.

Then, in 1997, a romantic comedy hit the theaters with an all-black cast and poetry as its centerpiece: Love Jones. The movie was an instant classic, and Lane’s poem, “Lyric: I am Looking at Music,” from Girl at the Window, was recited at one of the movie’s most climactic moments. Lane’s work was introduced to a new generation. Her poem’s inclusion in a black film about poetry proved that formal poetry can find its way into the performance poetry scene—even work by a black poet who was labeled “not black enough” for most of her career.

Eleven years later, in 2008, Lane died at the age of eighty-five.

Today, Southern University’s John B. Cade Library hosts an annual Pinkie Gordon Lane Poetry Contest. Students from all over the state submit their poems. Winners are invited to Southern University’s campus every April for an awards program that includes a keynote speaker and reception; these young writers have varied across poetic themes and racial lines.

In December 2017, an LSU student coalition dedicated to anti-racism petitioned the university to rename the John M. Parker Agricultural Coliseum on campus. Students say the former governor was a racist who participated in the lynching of Sicilian immigrants in Baton Rouge. They want his name removed from the building. They have requested that the building be renamed after Pinkie Gordon Lane, the first black woman to receive a PhD from Louisiana State University. A decision is pending this spring.

—

Kelly Harris holds an MFA in creative writing from Lesley University. She has received fellowships from Cave Canem and the Fine Arts Work Center. Harris currently serves as guest poetry editor of the University of New Orleans’ Bayou Magazine and is a Tennessee Williams Festival board member. Her poems have appeared in Valley Voices, Yale University’s Caduceus Journal, Southern Review, Say it Loud: Poems for James Brown, and more. She lives with her husband and daughter in New Orleans. She hopes to complete her collection of poems and essays this summer. Follow her work at kellyhd.com.