I Wanted to Read About the South: Becoming a Writer

An excerpt from Cherie Quarters: The Place and the People That Inspired Ernest J. Gaines, by Ruth Laney

Published: November 29, 2022

Last Updated: February 28, 2023

LSU Press

Note: Cherie Quarters, where Ernest Gaines grew up, was a small Black community in Pointe Coupee Parish comprising former slave and sharecropper cabins on the grounds of River Lake Plantation. The last two houses are now gone, despite having been named to the National Register of Historic Places.

Ernest Gaines was inspired to return to the South by the bravery of James Meredith, who was protected by armed guards when he integrated the University of Mississippi in 1962. Gaines also realized that he needed to return to Louisiana, to soak up its atmosphere, so he could finish his first novel, Catherine Carmier. He called relatives in Baton Rouge, who invited him to stay with them. In January 1963, he gave up his San Francisco apartment and left for Louisiana by train.He moved in with his great-uncle George Williams and George’s wife, Mamie, who lived on Louise Street in a primarily Black area known as the Bottom, north of LSU. Their daughter Lee was at college in California, but their fourteen-year-old son Joe was still at home, attending McKinley High School just around the corner. The four-bedroom house was crammed with people. “We had a house full,” recalled Ben Biben, who lived there after leaving Cherie Quarters. “Mamie loved having people around her.”

Community spirit was very much alive among Cherie Quarters residents who left for Baton Rouge. People moved in together and found work, paying minimal rent and grocery money, saving up until they could afford homes of their own. Sam Bibbens lived with the Williams family for eighteen months before moving to San Francisco. “We called it the Underground Railroad, where you went to [transition] from the farm to the city,” he said.

George Williams was a janitor at the Copolymer rubber plant and Mamie cooked in the cafeteria at the school for the deaf. Ben worked for a drugstore and a health club. Ernest Brooks (“Booster”) delivered groceries by bicycle and shared a bedroom with Little Joe. Every night, Mamie cooked for the extended family. “We had so much fun in that house,” recalled Ben.

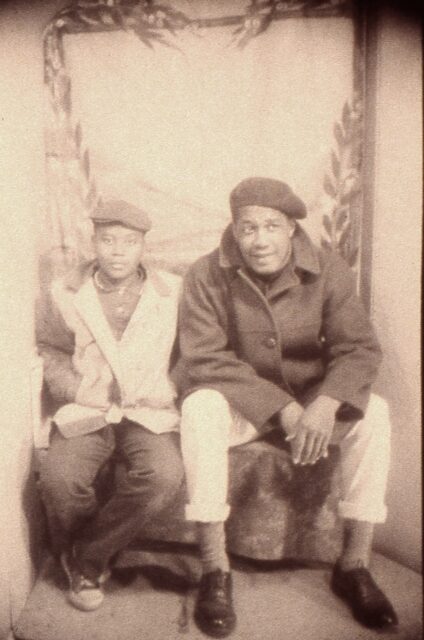

Ernest Gaines, about age twenty-seven, and his cousin Joe Williams, about eleven, in a photography studio on East Boulevard in Baton Rouge, circa 1960. Tony Cador.

Ernest Gaines was given a room of his own. Every day, after Little Joe set off for school and the others for work, Gaines went to his bedroom and typed on his Royal portable, re-creating the novel he had begun at sixteen. Three in the afternoon was “his magic hour” to quit work, Ben said. But sometimes Gaines got angry if disturbed, even for meals. Mamie often left a tray outside his door.

“He told me, ‘I will be a writer,’” said Ben. “Not, ‘I’m going to try to be a writer,’ but ‘I will be a writer.’” Gaines’s agent Dorothea Oppenheimer sent him money from California. “She somewhat supported him financially,” Ben said. “She had faith in him. We felt good about him going to the city and making something of himself.”

On January 15, 1963, Gaines turned thirty. After fifteen years in California, he had to readjust to the indignities of segregated bus stations, “colored” eating sections in restaurants, white cabdrivers who refused to pick him up. On visits to False River, he realized that life on the plantation had changed drastically since he had left in 1948. After the war, many men had not returned. Families had scattered to California, New Orleans, Baton Rouge. Most young adults were gone, leaving old people and children behind.

Gaines visited “the old people,” like colorful Walter Zeno and quiet Reese Spooner, who told him stories of people long gone—stories he would later use in his fiction.

On weekends, Gaines went out drinking in “some dives. Every Sunday night Ben and I went to the White Eagle in Port Allen. We’d park blocks away and could hear the music.”

Gaines’s life had been marked by turning points: moving to California, discovering the public library, meeting his agent. Equally crucial was his journey home, where he saw the quarter through a sensibility matured and broadened by his years away. As civil rights demonstrations raged throughout the country, he revisited a plantation mired in the Jim Crow past.

Gaines had found the source of his restlessness and frustration as a writer—he needed to connect with and make sense of his past. Later he saw his sojourn in Baton Rouge as a defining moment.

The six months I spent in Louisiana saved my writing and possibly my life . . . . I could never have written Catherine Carmier if I had not gone South, and maybe I would never have written any other book . . . because writing is my life. For me, not to write is not to live. So I went there, put up with many things I hated, but I learned much, much about the people and the place that I wanted to write about.

EXCERPT FROM:

Cherie Quarters: The Place and the People That Inspired Ernest J. Gaines

by Ruth Laney

$34.95; 304 pp.

Louisiana State University Press

October 2022