Summer 2025

Inspiring Shared Purpose

Norman C. Francis is the 2025 Humanist of the Year

Published: May 30, 2025

Last Updated: August 29, 2025

Courtesy of Xavier University of Louisiana

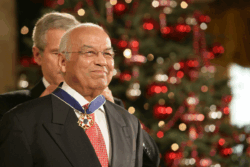

Norman C. Francis received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush in 2006.

In 1961, seven years after the US Supreme Court ruled that “separately is inherently unequal” and more than four years after the Montgomery bus boycott ended triumphantly for those demanding dignity in that city, a group of idealistic young Americans vowed to test a court ruling requiring equal accommodations in interstate travel. They boarded buses in Washington, DC, and set out for New Orleans.

When Norman Francis, then the thirty-year-old dean of men at Xavier University of Louisiana, heard about the “Freedom Rides” from two students active in the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), he predicted, “That bus will never make it to New Orleans.”

Violent white mobs in Alabama proved Francis right. Even so, a portion of Freedom Riders defiantly flew to New Orleans to make a symbolic show of reaching their final destination, and after the hotels and motels in the Crescent City vowed to deny them rooms, Francis—in a quietly subversive move—hid them. “I told them they could stay on the third floor of St. Michael’s Dormitory,” Francis told the Times-Picayune in 2015, explaining that the school’s then president “gave me the go-ahead on the condition we didn’t put out a press release.”

A young Norman C. Francis at his desk at Xavier University, 1980s. Courtesy of Xavier University

Though not as confrontational as the students on the front lines with CORE or the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, Francis was a civil rights pioneer in his own right. In 1952, he was one of two Black students admitted to law school at what was then called Loyola University of the South and was the first Black student to graduate. His admission to the law school followed years of pressure put on Catholic officials by some laypeople and students to integrate their schools and universities. Francis, a Xavier University mathematics major who was study body president and voted by his classmates as most likely to be secretary of state, served as vice chairman of the Southeastern Regional Interracial Commission, a Catholic student group that put some of that pressure on Catholic schools to integrate.

But even after Loyola’s law school admitted Francis, he was still prohibited from living on campus. He monitored a dormitory at Xavier to make money and earn his room and board.

“He’s not only better than everybody around him, he makes everybody around him much better.”

It makes sense, then, that Francis, who knew well the indignities of segregation and had spent the two years after law school assigned to the Army’s Third Armored Division in Frankfurt, Germany, would give cover to the young people trying to force America to live up to its ideals. The year before the Freedom Rides, some of his students were arrested for trying to force the integration of the lunch counter at McCrory’s department store on Canal Street in New Orleans; Francis had used his position as a young lawyer and dean of men at Xavier to advocate for them.

Lombard v. Louisiana, a landmark US Supreme Court case that helped lead to the desegregation of private businesses, had as its main plaintiff Rudy Lombard, national vice president of CORE and a Xavier University student whom Francis retrieved from jail at least once. Even after his lengthy tenure as president of Xavier University was over, Francis, in an interview, was still expressing admiration for the recently deceased Lombard’s passion for both his studies and his pursuit of freedom.

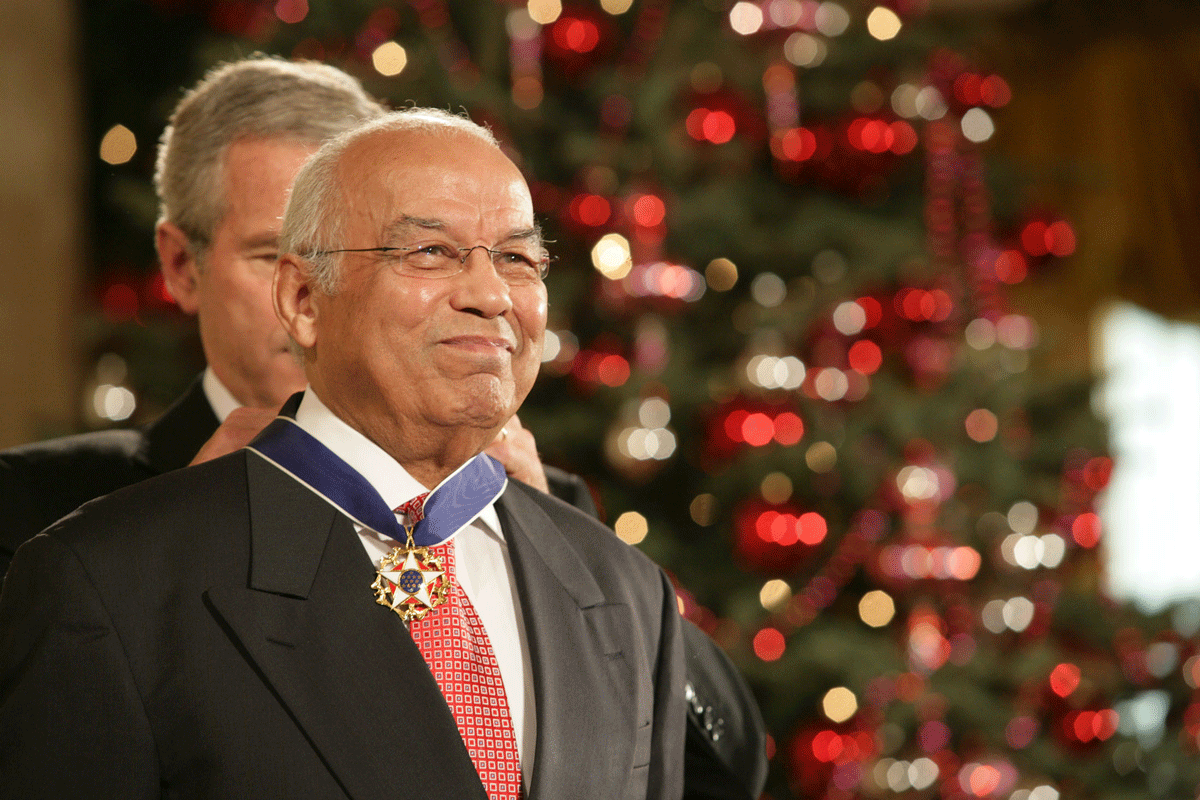

Norman C. Francis with Muhammad Ali during his visit to New Orleans in 1978. Courtesy of Xavier University of Louisiana

Norman Christopher Francis, the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities’ 2025 Humanist of the Year, was born in Lafayette, Louisiana, in March 1931—more than a year into the Great Depression—as the fourth of Joseph A. and Mabel F. Francis’s five children. Given his parents’ lack of wealth and the fact that neither had graduated high school, it’s unlikely that they could have conceived of him becoming the first lay president of the only Black Catholic University in the Western Hemisphere—or that he would receive, in 2006, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. When Georgetown University awarded him an honorary doctorate degree in 2015, the school’s press release noted that he’d been awarded forty-one honorary degrees already.

His most well-known accomplishment is certainly his leadership at Xavier University, where he stayed for fifty-seven years, forty-seven of them as president, making him, at the time of his retirement, the longest serving college president in the country. His time at Xavier was exceeded by his sixty-year marriage to the former Blanche Macdonald, who died in 2015. The couple raised four sons—Michael, Timothy, David, and Patrick—and two daughters—Kathleen and Christina. In 2022, seventy years after Loyola’s law school admitted Francis but barred him from living on campus, the university renamed its newest residence hall the Blanche and Norman C. Francis Family Hall.

One of the things that stands out about the husband, father, and college president is the amount of energy and focus he had left over for the city of New Orleans, the state of Louisiana, and, indeed, the United States. In 1983, Francis served on the National Commission on Excellence in Education, whose publication A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform focused on the shortcomings of public education in the United States. He has chaired the board of the Educational Testing Service in Princeton, NJ, which produces the SAT, the GRE, and advanced placement exams; the board of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching; and the board of the Southern Education Foundation. He’s a past president of the United Negro College Fund and a past chair of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools.

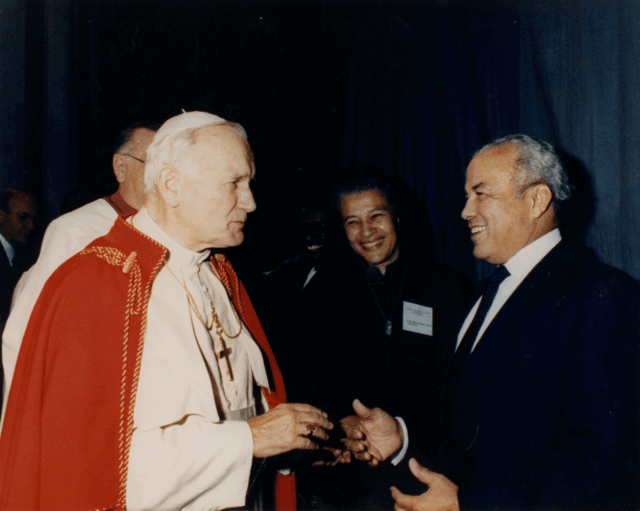

Norman C. Francis, seated two seats to the right of President Jimmy Carter. Courtesy of Xavier University of Louisiana

According to former New Orleans mayor and National Urban League President Marc Morial, Francis is “an incredible multitasker.” Morial said Francis deserves “credit for building two iconic New Orleans institutions,” Xavier University as well as Liberty Bank, “where he’s been the only chairman of the board for fifty years.”

“Liberty’s outlasted all the big banks in New Orleans,” Morial said. “Outlasted FNBC, outlasted Hibernia, outlasted the Whitney. Remains locally owned and locally controlled and is now the largest Black bank in the country.”

As for Xavier, Morial said it was already “an important institution when [Francis] took over its leadership in the late 1960s. But he made it something much different and much bigger and much more powerful. He made it a globally renowned undergraduate institution, historically Black, with a prowess in the sciences and the preparation of pharmacists and doctors.

“He understood before others did that a small university needed a niche.”

It was far from certain, after Hurricane Katrina and the accompanying levee failures of 2005, that Xavier was going to survive. With New Orleans mostly empty and underwater and with students and faculty scattered across the country, Francis, then 74, arguably had to exhibit more leadership and diplomacy than he ever had before.

When Georgetown University awarded him an honorary doctorate degree in 2015, the school’s press release noted that he’d been awarded forty-one honorary degrees already.

One might think that keeping Xavier solvent would be enough on his plate. But not Francis. He also answered Governor Kathleen Blanco’s call to co-chair the Louisiana Recovery Authority with journalist and then Aspen Institute president Walter Isaacson.

“I think Norman never said no to anybody,” said Angela Vallot, a lifetime friend of the Francis family who serves on Xavier University’s Board of Trustees. “I think that was part of the challenge, that he agreed to serve on everything. I think I read or was told that he served on a total of some fifty boards and commissions.”

In particular, Vallot said, Hurricane Katrina recovery “ultimately brought together all of Norman’s talents, his skills, his network, his love of New Orleans, his humanitarian interest. And that was a huge, huge job. And he got it done.”

As Louisianans “continue to rebuild from the devastation of the hurricanes,” President George W. Bush said in 2006 as he placed the Presidential Medal of Freedom around Francis’s neck, “the people of the Pelican State will benefit from the leadership of this good man. And all of us admire the good life and remarkable career of Dr. Norman C. Francis.”

“Listen, Norman came from nothing,” Vallot said. “I mean, his family was poor. And I think he really saw this opportunity to succeed. And the great thing about Norman is he made it. But he looked back.”

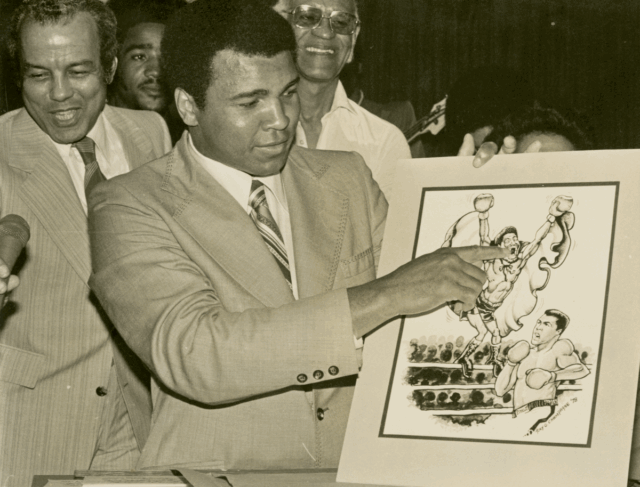

Norman C. Francis meeting Pope John Paul II during his visit to New Orleans in 1987. Courtesy of Xavier University of Louisiana

Despite his interactions with US presidents and the highest leadership in the Catholic Church, including Pope John Paul II, Francis never took on the characteristics of the comfortable. Not only was the college president known in his neighborhood for mowing his own lawn—meticulously—but after his retirement in 2015, the then eighty-four-year-old explained to a reporter why he still set aside time on Friday evenings to shine his own shoes. He had shined shoes as a boy on Lafayette’s Jefferson Street for twenty cents a customer and knew what the job requires. After he wasted five dollars on a subpar shoe shine on a business trip to San Francisco, he’d never pay anyone for a shoe shine again.

Because he was a law school graduate, when he was deployed to Frankfurt, he could have had a relatively cushy job, but he told a reporter that he wanted to serve his commitment as quickly as he could and, thus, served as a private. “It taught me humility,” he said. “I did anything any private did. I washed pots and pans. I walked guard duty in the snow. I ran with that big rifle.”

Ambassador Dwight Bush, a former member of the Xavier Board of Trustees who had a forty-year career in finance, recalled Francis sharing with him a seemingly unrealistic vision about construction projects that included a new convocation center, athletic facility, and dormitory. “To his credit,” Bush said, “everything that he discussed came to fruition.”

But even as he kept long-term goals in mind, Bush said, Francis wouldn’t let those ambitions or moments of financial difficulty deter him from the mission as laid out by the school’s founder, Katharine Drexel, to promote the education of Black students. On the occasions when parents were struggling to pay what they’d promised to pay for their student’s education at Xavier, Bush said, “Dr. Francis would always go back to mission. . . . It really came down to him saying, ‘OK, we might have to put off my vision of the new whatever while we help these families get through this difficult time.’”

Xavier’s reputation for staying true to its mission and not discarding families struggling financially complemented its reputation for not rejecting or discarding students struggling academically. One of the more remarkable anecdotes about Xavier, and the reputation it developed under Francis’s leadership, comes from Pierre Johnson, who was raised in a violent Chicago home by parents addicted to drugs and who graduated from high school without ever having heard of the periodic table. Xavier prepared him for medical school, and he now works as an OB/GYN with a specialty in treating uterine fibroid tumors. Speaking on campus in 2018, Johnson called Xavier University “my saving grace.” He said, “It would’ve been very easy for me to slip through the cracks during the academic valleys of my freshman year, but Xavier actively worked to identify and support students like me.”

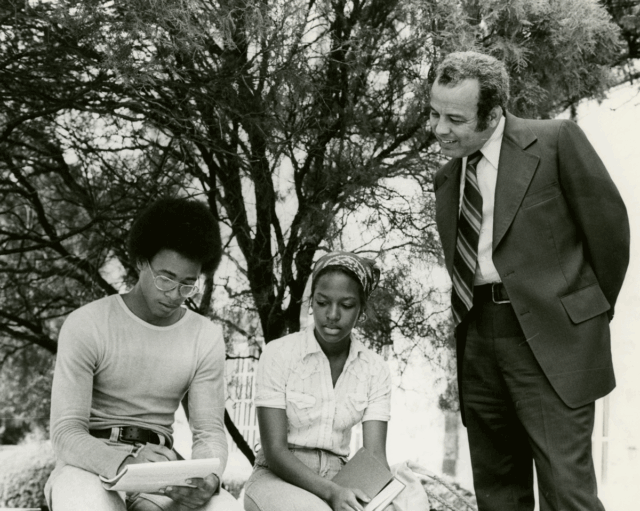

Norman C. Francis speaking with two Xavier University students, 1980s. Courtesy of Xavier University of Louisiana

Talk to enough people about Norman Francis, and one of the themes that emerges is that he has an irrepressible love of people, a finely tuned emotional intelligence, and the ability to talk to anybody, no matter their station or social status. Another theme that emerges is that he would have been successful no matter what career he’d picked.

He’s a “man who would have been great at anything he chose,” Morial said. “Had he chosen to be general manager/president of a professional sports team, he would have been great.”

“He could have gone into a law firm,” Vallot said. “You know, he jokes all the time that his father thought he was going to be a millionaire and return to Lafayette and, you know, practice law there. . . He didn’t make a whole lot of money as a college president, and he could have stayed in the private sector and done much better financially, but his calling was really to help people, and to take this university that Sister Katharine Drexel founded and to really expand it and turn it into something that would become nationally recognized.”

Isaacson has written biographies of world-changing figures including Leonardo da Vinci, Steve Jobs, and Albert Einstein. “If I could compare him to any of the great leaders, it would be Benjamin Franklin,” Isaacson said, “because Benjamin Franklin, just by his grace and calm, was able to unite people, even during a revolutionary period where you had passionate people like Samuel Adams and really smart people like Alexander Hamilton. You needed somebody who could bring people together and give them a sense of shared purpose, and that’s a leadership trait that we are lacking in our society today.”

Isaacson described a particular meeting of the Louisiana Recovery Authority where tempers flared and everything seemed to fall apart the moment Francis temporarily stepped out of the room—and everything immediately returned to order when he walked back in.

When asked what Francis had said or done to restore order, Isaacson said, “His presence is calming.”

He added, “He’s not only better than everybody around him, he makes everybody around him much better.”

Jarvis DeBerry is an opinion editor at MSNBC.com. His previous roles include founding editor of the Louisiana Illuminator and deputy opinions editor, columnist, and editorial writer at The Times-Picayune. He was on the team of journalists awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service for its coverage of Hurricane Katrina and the deadly flood that followed. His columns have won awards from the New Orleans Press Club, Louisiana/Mississippi Associated Press, and National Association of Black Journalists.