Book Excerpt

The Irish of New Orleans

An excerpt from Laura D. Kelley's book.

Published: March 16, 2016

Last Updated: May 9, 2019

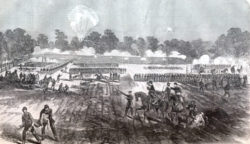

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The Battle of Irish Bend Louisiana sketched by William Hall for Harper's Weekly, May 16, 1863.

O’Reilly was born in County Meath in 1723 and came from a family with a tradition of military service; his grandfather had fought with James II as a colonel heading up the O’Reilly Dragoons. However, Alejandro’s military career did not unfold in the fight for Ireland, like that of his grandfather. His father, Thomas O’Reilly, had left Ireland as one of many of the Wild Geese, as the Irish emigrants of this era were called, and settled with his family in Zaragoza, Spain. At age 11, Alejandro joined the Spanish military and served as a cadet in the Hibernian Regiment (Regimiento de Hibernia). With a keen eye for strategy and talent for fighting, he soon reached the rank of brigadier.

General Alejandro O’Reilly, in a portrait by Aurora Lazcano, was the second governor of Louisiana under the Spanish flag. He earned the Nickname “Bloody O’Reilly” by ordering the exile, imprisonment, and execution of rebel Frenchmen in Louisiana. Courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum.

When O’Reilly arrived in New Orleans, he made a dramatic entrance, starting with a cannon salute while column after column of Spanish soldiers, among them many from the Hibernian Regiment, lined the three sides of the Place d’Armes (Jackson Square). On signal, 2,000 Spanish soldiers shouted, “Viva el Rey” while cannons onshore and on ships responded. Needless to say, O’Reilly quickly re-established Spanish rule. The king, in fact, had given O’Reilly broad authority for his mission to Louisiana to “organise [sic] legal proceedings and to chastise, conforming with the law, the exciters and associates of the insurrection.” The King ended his instructions stating that he “entrust[ed O’Reilly] with extensive and full power and authority” that extended to the use of force if necessary.

O’Reilly invited the leaders of the rebellion to dinner and proceeded to use this authority. He listened to their version of events and promptly arrested 13 of them. Adhering strictly to Spanish law, O’Reilly served as judge and jury during the trial. The defendants shared a common argument: Ulloa never presented his credentials (true); never raised the Spanish flag over the Place d’Armes (true); and, therefore, never took formal possession of the colony (also true). Consequently, the leaders of the rebellion argued, the defendants and the other participants in the rebellion had, in fact, expelled only a private citizen and therefore had not committed treason. It was a clever but unpersuasive argument that did nothing to change the guilty sentence O’Reilly pronounced on 12 of them. Six defendants were given death sentences, and the remaining six received long jail terms. All of them lost their property. The swift manner in which O’Reilly dealt with the rebellion earned him the moniker “Bloody O’Reilly.”

After imprisoning the remaining leaders, O’Reilly issued a general pardon from the King for all the other participants. He also required that all colonists take an oath of allegiance to the Spanish crown, a request with which everyone unsurprisingly complied. During the year of his stay in New Orleans, O’Reilly abolished the French Superior Council and established the Cabildo, with judicial, legislative, and executive authority. He instituted a Spanish code of laws and skillfully integrated French laws to ensure a smooth transition. He met with the chiefs of Indian nations—grand and petite—smoked the calumet with them, and promised to continue the French policy of annual gift-giving. He also outlawed Indian slavery. In addition, he introduced a Spanish version of the French Code Noir (the set of laws regulating both slaves and slave owners) that offered more rights for the enslaved and more paths to manumission.

Several of the Irishmen travelling with O’Reilly stayed in Louisiana after his departure. Maurice O’Connor was placed in charge of the militia, and Arthur O’Neill assumed the responsibility of negotiating with Native Americans. Another Irishman, Oliver Pollock, a merchant living in Havana, moved to New Orleans in 1769, and O’Reilly gave him the lucrative contract to supply the militia with flour.

Pollock benefited tremendously from the friendship with his fellow Irishman O’Reilly. The general not only gave Pollock the exclusive contract to supply the Spanish military, but he expelled all British merchants in the colony. Furthermore, he made trade with England, the traditional enemy of Ireland and Spain, illegal. Pollock remained in New Orleans, and with a near monopoly on many goods needed by the military, he quickly made a vast fortune.

The Irish of the colonial period, like “Bloody” O’Reilly or his friend Pollock, were part of the colorful, ragtag bunch of early inhabitants of New Orleans. While the French Company of the Indies records only two Irish sailors on its rolls, the colonial sacramental records of St. Louis Cathedral list many men and women from the Emerald Isle. These documents provide a compelling picture of the type of Irish immigrant that came to New Orleans and the reasons for emigrating during the colonial era. Not surprisingly, the records show that the two main avenues by which the Irish came to the city—the paths Alejandro O’Reilly and Oliver Pollock took—were typically military service or business.

The colonial era differed from the subsequent period in that it was marked by key individuals who happened to be Irish rather than by a large wave of Irish emigrants to New Orleans. No ethnic enclave existed yet; the city was a heterogeneous cluster made up of individual experiences. However, collectively, the Irish of colonial New Orleans were different in important ways from the Irish of the 13 British colonies. Irish immigrants there were primarily Presbyterians who would later become known as the “Scotch-Irish,” whereas Louisiana attracted Irish Catholics because it was part of the Catholic Atlantic World that also included France and Spain.

For the Irish in New Orleans, life during the early American period (1803-1815) proceeded much like it had under Spanish rule. They still came to the city attracted, primarily, by a fertile business climate rich in opportunity. However, one particular event, the failed 1798 Rebellion in Ireland, once again brought political exiles to New Orleans. But this time, these exiles were different for two reasons. The rebellion was led by the United Irishmen, which, true to its name, comprised Protestants and Catholics. The disastrous uprising was soon followed by the Act of Union in 1800. Both events dramatically changed the political landscape of Ireland. Unlike earlier immigrants, these new political exiles arrived in New Orleans with well-developed, politicized views of Ireland and a strong sense of Irish identity.

Freedom to Ireland, published by Currier & Ives, New York, ca. 1866. Members of the charitable Hibernian Society while following their mission to help “distressed” Irish immigrants also advocated for an autonomous Ireland. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Celebrating a Patron Saint

The first celebration of St. Patrick’s Day in New Orleans therefore occurred during this early American period. It has been widely, but erroneously, reported that the first recorded St. Patrick’s Day festivities were in 1809. However, the first event actually took place even earlier, in 1806, with a prestigious group of male residents gathering to celebrate the Feast of St. Patrick. The Orleans Gazette reported that an “excellent dinner” was hosted by “the Irish Gentlemen of the city.” “[T]he governor, Secretary of State, the Judges, Col. Freeman and several officers of the government and other gentlemen were guest.” The article informs further that “after dinner several appropriate songs were sung and the following toasts were drank [sic]”:

- The Day we celebrate

- The Mother of all Saints

- The President of the U. States—May his wife and vigorous councils be supported by an energetic Congress

- The memory of Gen. Washington

- The Armies that fight for the independence of their country

- The Army of the U. States

- The Navy of the United States

- The Commerce of the United States—may its resources continue ready to maintain the rights and dignity of the country

- The Venerable Clergy throughout the continent of America—May their influence ever be employed in the cause of freedom!

- The Irish Shamrock—may it find a congenial soil in the plains of Louisiana

- The Territory of Orleans—may its inhabitants soon enjoy all the privileges of American citizens

- The memory of Gen. Montgomery—one of the first who taught Irishmen to bleed for their adopted country

- Gen. Eaton—A handful of brave men is worth more than millions of dastards

- The three C’s of Louisiana—Cane, Cotton, and Corn!

- The King of Spain—may all his dominion be soon restored to their ancient Independence

- Our American brethren—may the resources of their country be applied to its aggrandizement

- The Fair of Louisiana—may the sons of St. Patrick ever deserve and be blessed with their smiles

- VOLUNTEERS—The True Sons of St. Patrick—May the Americans ever receive them as brethren.

- Gen. Moreau, and the brave Frenchmen who prefer exile to slavery.

Besides their obvious amusement value, these toasts are also indicators of the political mindset of this nascent ethnic group. The hierarchical order of the toasts reflects a telling mix of religious and secular, general and specific topics, espousing both patriotism and commercialism. There were also subtle—and not so subtle—references to the fight for Irish freedom and the oppression of British rule. Repeated associations with the American Revolution—for example, the toast to General Washington, not President Washington—were made for several reasons. This delicate distinction served as a reminder that the Irish participated in the rebellion and therefore should be considered patriots in the American cause; the toast also references the Irish struggle against England and the recent 1798 uprising in a similar light. Americans and Irishmen were “brethren” because they had a common enemy and both would “fight for the independence of their country.” Poignancy was added to this toast by the fact that in 1806 the British were yet again trampling on the United States’ rights in a series of events that would eventually lead to the U.S. declaration of war against Great Britain in 1812.

The end of the War of 1812 coincided with the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe. Both cessations affected Ireland negatively. During the long hostilities, high demand and low supply of many foodstuffs had benefitted Ireland. Prices dropped quickly after peace was established, causing economic stagnation and widespread unemployment in Ireland that persisted nearly two decades. To make matters worse, Ireland also suffered several bouts of bad weather with devastating effects on crops. These natural catastrophes were accompanied by the additional hardships of smallpox and typhus outbreaks. This combination of economic downturn, crop failures and deadly epidemics resulted in a wave of Irish immigrants heading for American soil. Unlike previous political exiles who were both Catholics and Protestants, the new arrivals were primarily Catholic, and most came from the laboring classes, forced to leave home to escape poverty and illness rather than political persecution.

To accommodate these new arrivals from Ireland, Judge James Workman and other Irishmen in the city in 1818 formed the Hibernian Society in New Orleans “for the purpose of affording advice and assistance to such of their distressed and deserving countrymen as may emigrate to this state.” Among the officers of this society was a “counsellor” [sic] and a “physician” whose duties were to “give their professional advice and assistance, gratuitously, to such natives of Ireland arriving at, or residing in this city, as the board of managers recommend in writing, as being in want and deserving of relief.” Members were asked to pay annual dues of $20 ($378 in today’s money) to finance their charitable work; alternatively, a lifetime membership could be purchased for a one-time payment of $200 ($3,780 now). The Hibernian Society met three times a year in addition to its great annual celebration of St. Patrick’s Day.

However, the vast majority of Irish immigrants who arrived in New Orleans did so as a result of the Great Famine.

The Great Famine and Irish New Orleans

In 1844, on the eve of the Great Famine, 8.5 million people lived in Ireland. In the next 10 years, nearly 2 million would emigrate and a further 1 million would die as a result of the catastrophe. The Great Famine opened the floodgates of out-migration from Ireland to countries around the world. Sixty years after the famine, in 1911, the population of Ireland was only 4.39 million, a little more than half of its 1841 base.

Ireland was composed primarily of rural communities, but it was also a densely populated place. For example, in the west of Ireland, the average population density was 1000 people per square mile, whereas for the rest of the island an average of 700 people per square mile lived on cultivated land. Moreover, by 1845, due in part to the Penal Laws, the practice of subdividing land had forced the vast majority of Irish Catholics to survive on tiny portions of land. Illustrative of the increasingly smaller plots were the names given to these landholdings. The original plot, called a cow’s grass (described as enough land to feed one cow) was divided among the children and then divided again among the grandchildren. The first division was referred to as a cow’s foot and the second division as a cow’s toe. A cow’s toe was only one-quarter the size of a cow’s grass. This subdivision continued with each generation of children. Over time, it forced increasingly more people to rely upon smaller and smaller patches of land. This dependency on arable land barely large enough to provide even the most basic subsistence, made those who had to live off the products of these tiny plots much more susceptible to natural catastrophes. Furthermore, politics and prejudice compounded this precarious situation and helped set the stage for one of the greatest famines in modern times, one that fundamentally changed the history and demographics of the island.

Courtesy of Laura Kelley.

On these small bits of land, sometimes no larger than a quarter acre, the Irish produced food for home consumption. Since the mid-1700s, the cultivation of potatoes had increased dramatically in Ireland. A primary reason was that the potato root proved useful for breaking up the soil in preparation for sowing grain, Ireland’s primary export. Also, even a very small plot of land can yield enough potatoes to sustain a fairly sizeable family. Moreover, the potato was a reliable food source and quite nutritious. The number of childhood diseases and related infant deaths therefore decreased, while health in general improved among the Irish in the century before the Great Famine.

Thus, by a combination of government policy (Penal Laws), economics (international trade) and common sense (cultivation of a nourishing, reliable food crop), a vast and growing portion of the Irish population had, by 1845, become dependent on the potato. In fact, some 40 percent of the Irish population (more than 3 million people) relied on the potato as its main source of nourishment. In places such as Galway, the rate was even higher: nearly 60 percent of the people in that county lived off potatoes. Unimaginable by modern standards of nutrition, the average Irish adult male ate more than 14 pounds of potatoes daily, whereas women and children over the age of 10 consumed around 10 to 12 pounds, and younger children five pounds a day.

While the potato provided a steady food source—more reliable than grain, for example—poverty in Ireland was widespread and extreme. The third- and fourth-class housing that dominated the countryside was inhabited by families with very meager belongings. In 1837, the National School from Gweedore, County Donegal, compiled an inventory for the 4,000 inhabitants of this parish. Their entire combined material wealth consisted of the following: 1 cart, no coaches or vehicles, 1 plough, 20 shovels, 32 rakes, 7 table forks, 93 chairs, 243 stools, 2 feather beds, 8 chaff beds, 3 turkeys, 27 geese, no bonnet, no clock, 3 watches, no looking glass above 3 pence in price, and no more than 10 square feet of glass. Even ordinary clothing was sparse. Dresses as well as jackets were often shared throughout the community. Shoes were also scarce, and it was not uncommon to see them carried, rather than worn, to the market or fair to prevent wear and tear.

Such was the state of Ireland on the eve of the Great Famine: densely populated by predominantly large, poor families that depended for their survival to an extreme degree on the amount of potatoes they could grow on tiny patches of land.

So who had the resources to emigrate?

Obviously not the very poor in these first years of the famine, as is so often assumed. Not only did the poor lack the money to pay for the cost of the journey, but their extreme poverty made them particularly vulnerable victims of this great tragedy. Rather it was Ireland’s middling crowd who left and initiated an outward chain migration that would continue for more than 50 years. “Those who were best off, at once sold what they had, and emigrated, leaving the poorest behind,” one observer wrote in 1847. Another account notes that “large farmers … are hoarding up their money … withholding their due from the impoverished landlord, in order that they may on the first opportunity escape from the famine-stricken island to the unblighted harvests of America.”

Given the very high relative cost of the ticket, one would expect that it was mainly individuals traveling alone without family members who emigrated to New Orleans. Fleeing the famine, these individuals could have left their families and escaped to save their own lives; alternatively, they could have traveled alone for the purpose of making enough money and, once settled, sending passage fares home for family members. Curiously, and contrary to popular assumptions, neither was the case. In fact, during the 1847-48 travelling season, the majority of immigrants to New Orleans came as family groups. Not even a quarter of the immigrants were traveling alone; the vast majority, 78 percent, traveled with at least one other family member. In fact, nuclear families—families composed of a father, mother, and child[ren]—represented nearly one-third of all immigrants who made the journey to the Crescent City that season.

The high percentage of family members traveling together is not just an indication of financial wherewithal, but also reveals the strength of filial ties. Irish families, even in the face of a major catastrophe, whenever possible, stayed together.

When entire families could not travel at once, the Irish employed what historians call chain migration, a strategy that involves temporarily splitting the family unit to overcome various obstacles, whether financial, health, or otherwise. Individuals are sent abroad with the intention that once settled, they would earn enough money to pay for the remaining family members to make the journey. How many Irish immigrants followed this pattern is difficult to determine. But the large number of remittance offices, contemporary commentaries, and the fact that nearly $20 million ($57.8 million in today’s cash) in remittances were sent to Ireland in the first 10 years after the famine alone are persuasive evidence that chain migration was widely utilized. It was this continuing chain migration that allowed the wave of immigrants to become an unabated torrent that continued for the next 50 years.

Why New Orleans?

New Orleans in the 1840s and until the beginning of the Civil War was the second-largest port in America (behind only New York, which had just eclipsed the city for this position in the late 1830s) and the fourth-largest port in the world. A tremendous volume of goods constantly needed to be moved from one point to another for the port, the economic engine of the entire region, to run smoothly. In 1855, for example, a year when 2,266 vessels carrying nearly 1 million tons of cargo entered New Orleans, drays alone moved nearly 1.5 million bales of cotton, 94,000 hogsheads of tobacco, and 18.3 million gallons of molasses. The Irish monopolized this field. As one contemporary visitor noted, the merchandise had “scarce[ly] … touched the levee, when swarms of Irish” loaded the items onto their drays and charged off to their respective destinations.

Port-related work meant not only job security for the Irish but also political and economic power once they dominated any one field. In the 1850s alone, 30,577 steamboats docked in New Orleans, an average of nine a day. By this time, new immigrants escaping Ireland’s famine had enormously increased the Irish presence in the U.S., and, as a result, Irish labor had come to dominate many of the positions on board these vessels. In particular among the steamboat men, the Irish were known to be quarrelsome and assertive in their demands, with persuasive aggressiveness. Criticized for acting in unison and defending their own, they were described by contemporaries as being “clannish and unwilling to bend to the authority of the mate.” Deckhands often refused to work at the very last minute, forcing the captain either to waste precious time finding an entirely new crew or to acquiesce to their demands. For instance, on November 8, 1852, deckhands in New Orleans abandoned their work, insisting on a pay raise to $60 a month. They proceeded to picket along the levee, much to the chagrin of the steamboat owners and officers. Anyone caught trying to cross the picket lines was met with blunt force.

Port-related work meant not only job security for the Irish but also political and economic power once they dominated any one field. In the 1850s alone, 30,577 steamboats docked in New Orleans, an average of nine a day. By this time, new immigrants escaping Ireland’s famine had enormously increased the Irish presence in the U.S., and, as a result, Irish labor had come to dominate many of the positions on board these vessels. In particular among the steamboat men, the Irish were known to be quarrelsome and assertive in their demands, with persuasive aggressiveness. Criticized for acting in unison and defending their own, they were described by contemporaries as being “clannish and unwilling to bend to the authority of the mate.” Deckhands often refused to work at the very last minute, forcing the captain either to waste precious time finding an entirely new crew or to acquiesce to their demands. For instance, on November 8, 1852, deckhands in New Orleans abandoned their work, insisting on a pay raise to $60 a month. They proceeded to picket along the levee, much to the chagrin of the steamboat owners and officers. Anyone caught trying to cross the picket lines was met with blunt force.

Irish immigrants consciously pursued those jobs that offered opportunity and the chance for financial gains. As a group, the Irish were particularly skillful in appropriating and using to their advantage the economic opportunities offered in New Orleans, even to the extent of entirely controlling important sectors of the city’s commerce and industry. Contrary to popular opinion, the Irish of New Orleans were much more than just laborers or ditch diggers. In fact, among the Irish men who came here, nearly every field from doctors to druggists, professors to undertakers was represented.

The history of the Irish who emigrated to and lived in New Orleans was not, as some scholars have mistakenly claimed, the history of a people “undetermined and afraid to act.” Their actions, whether protesting poor work conditions, picketing for higher wages, or appropriating an entire, vital sector of the port economy show a strong, proactive, and dynamic group in the process of carving out a space for itself in a new home.

These qualities also extended to the Catholic Church when the Irish rallied behind Bishop Antoine Blanc in a controversial issue. In 1843 Irish Catholics had been deeply offended when the trustees, or “marguilliers” as they were called in New Orleans, denied Bishop Blanc entry into St. Louis Cathedral and refused to surrender control over the appointments of priests. The Irish were incensed at the arrogant behavior of the marguilliers and their Creole supporters. To the Irish they were “evil minded persons styling themselves Catholics.” In response to the insult, the Irish Catholics of St. Patrick’s Total Abstinence Society offered to march all 1,570 members to St. Louis Cathedral and physically remove the marguilliers. Bishop Blanc used this animosity between the lay trustees, who were mainly Creoles, and the Catholic parishioners who had been offended by the trustees’ actions, to strengthen his own position within the church. Blanc succeeded in defeating the domination of the marguilliers over the church, in large part due to the support he received from the Irish immigrant community.

——–

Excerpted with permission from The Irish in New Orleans (University of Louisiana Lafayette Press, 2014) by Laura D. Kelley.

Laura D. Kelley, Ph.D., is the Academic Director of Tulane’s Dublin Summer Program and a history professor at this university. Her primary focus of research for the last 20 years has been the Irish in New Orleans. She is among a team of scholars preparing events for the International Irish Famine Commemoration that will take place in New Orleans from November 6-9. For more information, log on to www.ifnola2014.org.

Click here for the interview with Laura Kelley by David Johnson.

- The Great Famine was not the only time disaster struck Ireland. For example, from 1816 to 1818, more than 50,000 people died in Ireland as a result of famine, smallpox or typhus..

- Even today, the combined population of the Republic of Ireland, at 4.5 million, and Northern Ireland, 1.8 million, totals only 6.3 million—still 25 percent less than before the Great Hunger took its toll.

- Numerous causes were responsible for the devastation wrought by the Great Famine. Among them were the laissez-faire economic policies of the British government and the moralism of Sir Charles Trevelyan. As assistant secretary to the Treasury, Trevelyan was in charge of administering relief during the Great Famine. He insisted that because “the judgment of God sent the calamity to teach the Irish a lesson, that calamity must not be too much mitigated. … The real evil with which we have to contend is not the physical evil of the Famine, but the moral evil of the selfish, perverse and turbulent character of the people.”

- After visiting a village near Skibbereen, Nicholas Cummins, a Cork magistrate, wrote to inform the Duke of Wellington of the dire situation in Ireland; his letter was also published in the Times on Christmas Eve of 1846: “I was surprised to find the wretched hamlet apparently deserted. I entered some of the hovels to ascertain the cause, and the scenes which presented themselves were such as no tongue or pen can convey the slightest idea of. In the first, six famished and ghastly skeletons, to all appearances dead, were huddled in a corner on some filthy straw, their sole covering what seemed a ragged horsecloth, their wretched legs hanging about, naked above the knees. I approached with horror, and found by a low moaning they were alive—they were in fever, four children, a woman and what had once been a man. It is impossible to go through the details, suffice to say, that in a few minutes I was surrounded by at least 200 of such phantoms, such frightful spectres as no words can describe.”

- During his visit to the United States in 1846-47, British traveler Alexander MacKay asked a Hibernian fellow passenger whether he believed that his countrymen improved their lot in America. With no hesitation and in all truthfulness the man replied, “Ah sure, but they do! Isn’t anything an improvement upon Ireland.”