Parish Spotlight

King Creole Turns 60

On location in New Orleans, Elvis staked his claim as an actor

Published: December 3, 2018

Last Updated: June 1, 2023

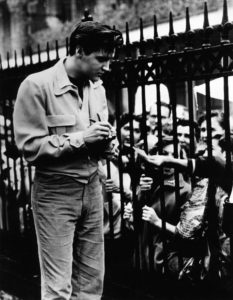

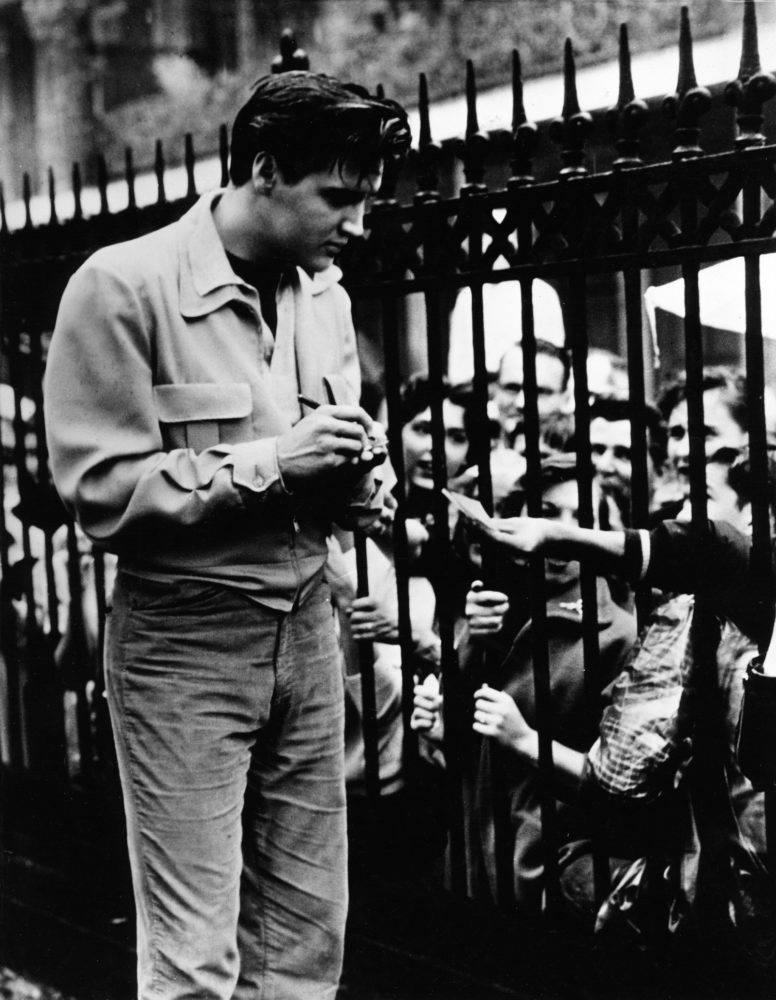

Alamy Images

Elvis Presley signs autographs on the set of King Creole.

Shot in moody black-and-white, King Creole is universally hailed as Presley’s best film. The movie’s star agreed. “Honey, that was my favorite picture,” he told actress Jan Shepard, one of his King Creole co-stars, on the set of Paradise, Hawaiian Style in 1966.

In the Vieux Carré–set King Creole, Presley plays a young singer plagued by bad luck and trouble. His angry-young-man character, Danny Fisher, gets entangled with Maxie Fields, a sadistic gangster who rules Bourbon Street. Complicating things, Danny falls for Maxie’s tragic girlfriend, Ronnie.

Future Oscar-winner Walter Matthau plays the ruthless Maxie; Carolyn Jones, who’d later portray Morticia in TV’s The Addams Family, is Ronnie; Dolores Hart plays Nellie, the five-and-dime store counter girl Danny dates; and Vic Morrow, previously seen in 1955’s The Blackboard Jungle, plays Shark, the knife-wielding delinquent Danny can’t shake.

When producer Hal Wallis asked Michael Curtiz, who’d previously directed Humphrey Bogart and Ingrid Bergman in Casablanca and James Cagney in Yankee Doodle Dandy, to guide Presley in King Creole, the sixty-nine-year-old director laughed. Wallis persisted, telling Curtiz that Presley needed “someone who can really discover him.” “Elvis,” Curtiz countered, “needs to be discovered as much as Marilyn Monroe and Jayne Mansfield do.”

Despite his skepticism, Curtiz signed on for King Creole. The great director quickly changed his tune about Presley. “Instead of a gyrating rock-and-roller,” he told United Press International, “I was watching a natural, un-actory actor, underplaying his role because he knew none of the tricks of the trade.”

Presley proved himself further by being the first person on the set, knowing his lines, and doing whatever the director wanted. Shepard, who plays Presley’s older sister in the film, told his biographer, Peter Guralnick: “Curtiz thought Elvis was going to be a very conceited boy. But when he started working with him, he said, ‘No, this is a lovely boy, and he’s going to be a wonderful actor.’”

The cast and crew of King Creole faced a deadline. On December 20, 1957, the world’s most popular singer picked up his military induction notice at the Memphis Draft Board. Presley requested a sixty-day deferment. Not because he wasn’t ready to enter the military, he explained, but because Paramount Pictures invested $350,000 in preproduction costs for King Creole. The draft board granted the request the day after Christmas. “I’m glad for the studio’s sake,” Presley responded. “I’m glad they were nice enough to let me make this picture, because I think it will be the best one I’ve made.”

In January and February 1958, Presley filmed scenes for King Creole at Paramount and recorded songs for the movie’s soundtrack at Radio Recorders Studio. Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller—the composers of “Hound Dog” and “Jailhouse Rock”—supervised the sessions.

In late February, Presley and a small group of his friends traveled by train to New Orleans for location shooting. The rest of the cast and crew flew to Moisant International Airport (later renamed after Louis Armstrong). Everyone arrived in the city on Saturday, March 1. Because mobs of fans prevented Presley from entering the Roosevelt Hotel, he reached his tenth-floor room via the roof of an adjacent building and a fire escape.

Security challenged the production throughout its eleven days in New Orleans. “When we were making King Creole,” actress Dolores Hart told the Elvis Australia website, “he had so many people after him. We couldn’t walk through the streets in New Orleans. It was like a circus. You would not believe the crowds. Policemen were everywhere.”

Nevertheless, King Creole fully exploits its French Quarter locations. Scenes take place on Bourbon Street, Royal Street, Jackson Square, Pirate’s Alley, and at McDonogh 15 School on St. Philip Street. Presley’s Danny sings the movie’s opening song, “Crawfish,” from a Royal Street balcony. A haunting duet, it co-stars jazz singer Kitty White as a horse-and-buggy driving crawfish vendor on the street below.

Hart and Jones play Presley’s two romantic interests in King Creole. Jones, speaking of the passionate scenes she shares with the film’s twenty-three-year-old star, said he “doesn’t need any training. The kids watching the shooting in New Orleans got the biggest kick out of it. Whenever Elvis put a hand on me, they’d go wild.”

Matthau complimented Presley, too, saying he knew “how to play the character simply by being himself through the means of the story. He was no punk.” Curtiz described him as an “amazingly restless, ever-searching young man . . . Elvis is agile and resilient with a smoothness that you’d expect in a veteran.”

When King Creole opened on July 2, 1958, Curtiz’s predictions that Presley would impress came true. “He delivers his lines with good comic timing, considerable intelligence and even flashes of sensitivity,” The Los Angeles Times reported. The New York Times’ reviewer expressed his surprise: “Elvis Presley can act. . . . [I]t’s a pleasure to find him up to a little more than Bourbon Street shoutin’ and wigglin’ in this shrewdly upholstered showcase.”

New Orleans’ Times-Picayune, however, labeled King Creole a sex-filled B-movie only Presley fans could love. “Though most unpleasant,” critic Janice Russo added, “the continual yells from the juvenile audience did serve a useful purpose. They drowned out most of Presley’s musical ‘innovations.’”

During rock and roll’s golden age, hostility for the music and its creators was common. Rock and roll, Frank Sinatra said in 1957, “is the most brutal, ugly, desperate, vicious form of expression it has been my misfortune to hear.” Presley responded to Sinatra’s condemnation with grace and humor. “I admire the man. He has a right to say what he wants to say. He is a great success and a fine actor. But I think he shouldn’t have said it. He’s mistaken about this. . . . I consider it the greatest in music. It is very noteworthy—and namely because it is the only thing I can do.”

King Creole proved Presley was good for more than rock and roll. But by then, he was in the Army at Fort Hood in Texas. Before his induction, he typically presented a stalwart face to the press about his pending military service. In private, he’d told friends he was devastated. Barbara Pittman, whom the singer had known since childhood, told Guralnick: “He kept saying, ‘Why me? My taxes would be more important than sticking me in the service.’ He was crying. He was hurt.” Speaking to another friend, Alan Fortas, Presley said he wanted to do his best in King Creole because it might be his last shot at making movies.

On March 14, 1958, ten days before his induction, Presley returned to Graceland from Hollywood. A Memphis reporter asked if he worried that his fans would forget about him during two years of military service. “That is the $64 question,” a wistful Presley answered. “I wish I knew.”

After the Army, Presley’s film and music careers were far from over. But he’d never make a movie better than King Creole.

John Wirt writes about music, film, and other things. He’s the author of Huey ‘Piano’ Smith and the Rocking Pneumonia Blues.