Summer 2025

Leap of Faith

A new exhibition celebrates the growth of New Orleans’s Vietnamese community over the past half century.

Published: May 30, 2025

Last Updated: May 30, 2025

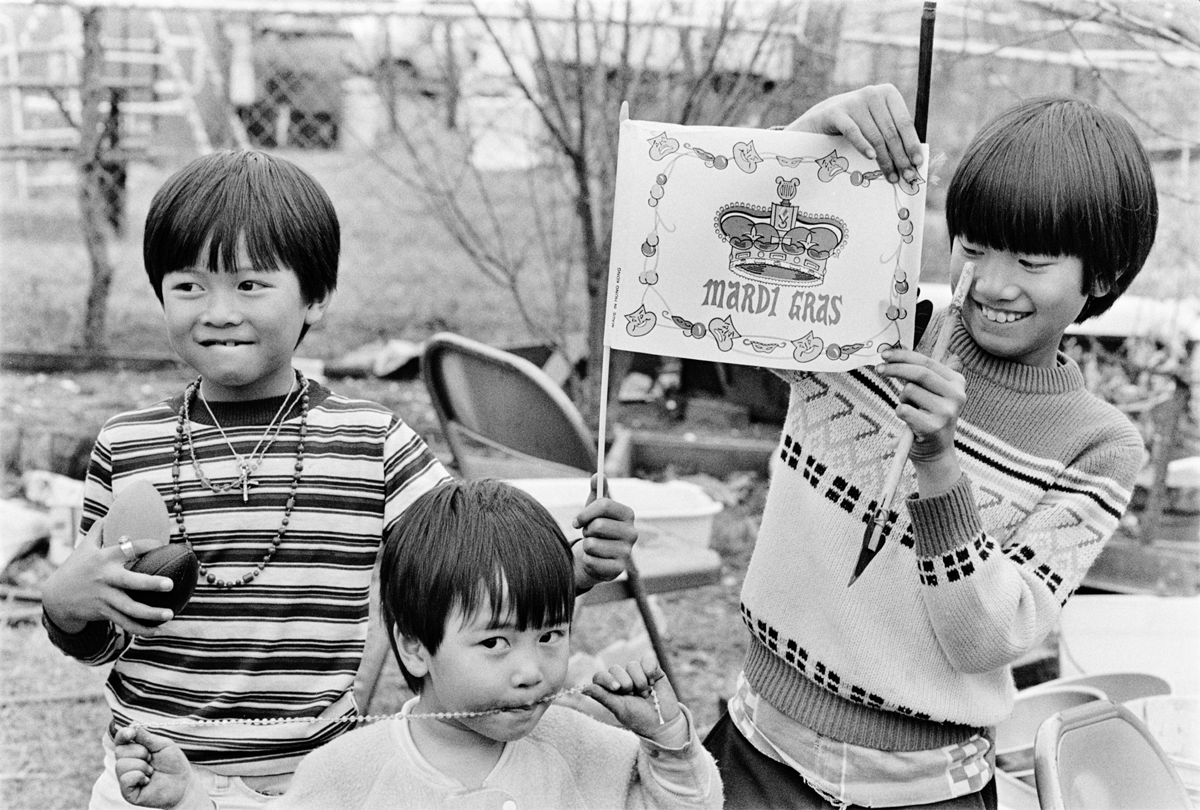

Children with Mardi Gras parade souvenirs in the Versailles community of New Orleans East, 1985.

HNOC. Photo by Mark J. Sindler, acquisition made possible by the Laussat Societ, 1975.

Fifty years ago, as North Vietnamese forces captured the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon, Kiem Do, deputy chief of staff for operations of the South Vietnamese navy, executed a secret evacuation of over thirty thousand soldiers and civilians aboard thirty-two32 naval vessels, which he turned over to US forces in international waters. In the chaos of the escape, Do was separated from his own family. After landing in a refugee camp in Guam, he recalled, “I just work[ed] from 10 to 10 to look for my family.” He eventually located his wife and five children in a camp on another island. Together, they traveled more than seven thousand7,000 miles to begin a new life in the United States.

Do’s story is one of many told in Making It Home: From Vietnam to New Orleans. The exhibition is built around interviews from The Historic New Orleans Collection’s Viet Chronicle project, a decade-long initiative to collect oral histories from the local Vietnamese community. The exhibition, which is presented in English and Vietnamese, weaves interviews with first-generation refugees together with photographic portraits, family heirlooms, and community artifacts to explore the establishment of one of south Louisiana’s most distinctive and resilient communities.

While the exhibition marks the fiftieth anniversary of the fall of Saigon in 1975, many of its featured stories began even earlier, in the twilight of the French colonial empire in Southeast Asia. Making It Home opens with artifacts from this first period of displacement, when the partition of Vietnam in 1954 led hundreds of thousands of villagers from the newly communist north to flee to US-supported South Vietnam. A photograph from this period shows North Vietnamese refugees boarding a naval ship to move south, while a poster produced by the United States Information Agency declares in Vietnamese that communism means terrorism.

Two decades of war followed, as reflected in the exhibition by South Vietnamese military uniforms, a US Silver Star medal awarded to South Vietnamese soldier Cường Văn Nguyễn, and a photo of an airstrike on a Việt Cộng hideout. Some 2.7 million US troops eventually served in Vietnam, and a 1969 image of an antiwar protest at Tulane University captures the domestic tumult that resulted. The end of this period is represented by footage of President Gerald Ford’s 1975 speech, also at Tulane, declaring that the Vietnam War was “finished as far as America is concerned.”

The refugees’ journey from Vietnam to the United States was a difficult and dangerous one. For some, it came immediately on the heels of the fall of Saigon in 1975. Others undertook the trip in the 1980s andor even ’90s, fleeing human rights abuses or hoping to reunite with relatives already settled in the States. Many families first had to endure the privations of refugee camps in Singapore and the Philippines before arriving in US relocation centers like Fort Chaffee, Arkansas.

In New Orleans, thanks to Catholic Charities’ preexisting resettlement program for Cuban refugees, several thousand Vietnamese people were placed together in apartment complexes, so they could help each other adjust to their new environment. They quickly established tight-knit enclaves, especially in the New Orleans East neighborhood that would come to be known as Versailles.

A recently acquired collection of photographs by Mark J. Sindler, who lived in Versailles, provides an intimate view of the Vietnamese community during the first decade of resettlement. Sindler documented his neighbors’ efforts to establish gardens, businesses, and the Church of the Vietnamese Martyrs, which later became Mary Queen of Vietnam Catholic Church, anchoring one of the first Vietnamese Catholic parishes in the United States. Photos and family heirlooms provided by members of the community also illustrate how the next generations left their mark on the city’s landscape and culture.

Making It Home includes interactive replicas of a living room and kitchen, where visitors can listen to Viet Chronicle oral histories and watch video clips that recount the journey to the United States, the experience of starting over, and even the influence of the local new wave music scene on American identity. Excerpts from Leo Chiang’s video documentary A Village Called Versailles reveal how the community rebuilt itself after the Hurricane Katrina levee failures, only to have to fight the city’s placement of a toxic landfill nearby.

The fiftieth anniversary of the fall of Saigon presents an opportunity to look back on how generations of Vietnamese people navigated trauma and displacement to establish a rooted community here in New Orleans. Making It Home continues the The Historic New Orleans Collection’s commitment to documenting and sharing the experiences of this community. The exhibition is on view through October 5, 2025.