Summer 2025

A Life Behind the Lens

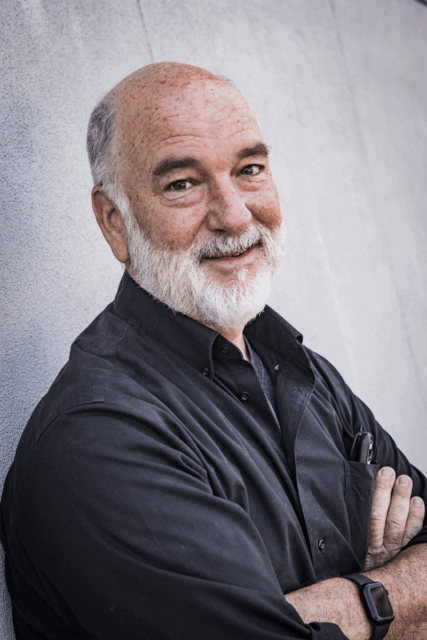

Pableaux Johnson (1966-2025) is the 2025 Documentary Photographer of the Year

Published: May 30, 2025

Last Updated: August 29, 2025

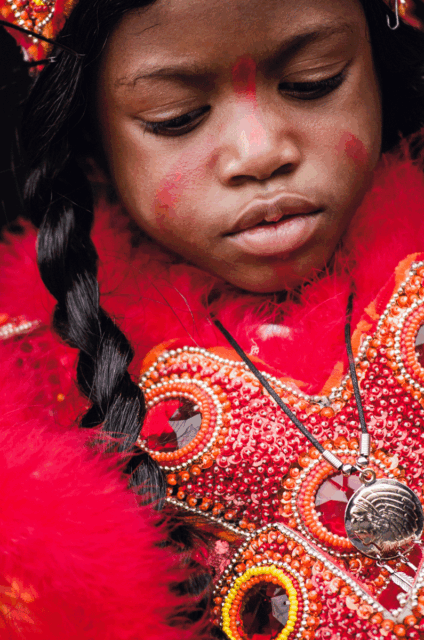

Photo by Pableaux Johnson

A Black Masking Indian in the Bayou Super Sunday Indian Cha Wa Parade on March 29, 2015.

The Documentary Photographer of the Year Award is given annually to a photographer whose work “captures Louisiana’s history, culture, and/or peoples.” Pableaux Johnson tirelessly photographed New Orleans cultural events including Black Masking Indians, second lines, and marching bands. Johnson’s portfolio is itself an archive of thousands of resplendent, imposing portraits of the city’s culture bearers. He freely provided prints to those who were captured in his images, maintaining a relationship of mutual respect and good will. A talented writer and engaged community member, Johnson is also known for his food writing and famous Monday red beans and rice dinners around his grandmother’s table.

On January 26, 2025, not long after receiving notice he would be honored with this award, Johnson passed away suddenly while photographing a second line. In lieu of recent images of Johnson’s work accompanied by his own commentary, the following pages contain images Johnson took between 2013-2015, accompanied by text from the glowing letters of support the LEH received from arts advocates and culture bearers nominating Johnson for the award.

— 64 Parishes editorial

2025 Documentary Photographer of the Year Pableaux Johnson (1966-2025).

“Pableaux Johnson was raised in New Iberia, Louisiana, with an intimate understanding of Cajun foodways through his family’s home-cooking. He worked for years as a food and travel writer, publishing with the likes of the New York Times, Saveur, Food and Wine, and Bon Appetit, and writing the books Eating New Orleans: From French Quarter Creole Dining to the Perfect Poboy (2005) and Lonely Planet’s World Food New Orleans (2000). While his photographs often accompanied his writings, it wasn’t until after moving to New Orleans in 2001 that he began to immerse himself in documenting the city’s living traditions and forming lasting relationships with cultural ambassadors. He has amassed an archive of tens of thousands of images of Black Masking Indians, brass band musicians, Social Aid & Pleasure Club Members, and school marching bands. In addition to photojournalism and museum shows, Pableaux is known above all for “repatriating” his work: he freely gives prints and digital copies of to the subjects themselves. This commitment to reciprocity—with hundreds, if not thousands, of New Orleans culture-bearers—adds a crucial ethical dimension to his work. There are numerous photographers who focus on outdoor performance traditions in New Orleans but Mr. Johnson’s images stand out because of a signature aesthetic approach. On the one hand, he is an action photographer, always responding in the moment in “live” events such as second line parades, jazz funerals, Mardi Gras parades, Super Sunday, St. Joseph’s night, and Jazz Fest. On the other hand, Mr. Johnson’s lens is drawn to individuals, capturing portraits of people as they go about their intense dedication to their craft in the moment. The result is an intimate glimpse of someone’s unique spirit and individual flair: flashing gold teeth, a handsewn beaded patch, a meticulously close fade hairstyle, wide-brimmed lavender fedora, or personalized dance move. From a technical perspective, this intimacy requires enough proximity to capture facial expressions that say so much but from a respectful distance that does not interfere with dancing, strutting, or playing an instrument. But there is an unspoken political element as well: because most subjects are Black New Orleanians and they invest such deep pride in their local traditions, there is a profound dignity to the expressions of joy, mourning, and even ferocity in the case of Indians or marching band members. Notice how the portraits are often at eye level or looking up, so the subjects are rendered are life-size or larger-than-life, never diminishing or patronizing them.”

— Matt Sakakeeny, Associate Professor of Music at Tulane University

An Extraordinary Gentlemen Social Aid and Pleasure Club second line parade led by Anthony “Head Honcho” Sims in 2016.

Photo by Pableaux Johnson

“His pictures have recorded thousands of history-making events that will tell the story of today to many tomorrow. He once has been a light to the culture of New Orleans and I am not just speaking of his flash.”

— Norman Dixon Jr., President of the Young Men Olympian Junior Benevolent Assc. Co.

The Ninth Ward Comanche Hunters Tribe of Black Masking Indians, led by Big Chief Keke Gibson, at Super Sunday 2015. Photo by Pableaux Johnson

“I have never met a photographer or cultural documentarian more professionally dedicated and personally engaged with the process of getting it right in terms of working in and with the represented communities. He ‘walks the walk.’”

— Patrick A. Polk, Senior Curator of Latin American and Caribbean Popular Art, Fowler Museum at UCLA

Little Chief Cameron Bourne of the White Cloud Hunters Tribe at Jazz Fest 2014. Photo by Pableaux Johnson

Mr. Johnson says that the parades are part of a spiritual practice in his life. Like church, he says he receives more than he gives. It is part of the call and response ethic of his work in the city that is backed up with an incredible eye for the gorgeous diversity of self and communal expression from our neighborhoods.

— Rachel Breunlin, Director of The Neighborhood Story Project

The Hard Head Hunters led by Flagboy Robert “Slim” Stevenson at Jazz Fest 2014. Photo by Pableaux Johnson

“Where some see colors, Pableaux sees communities. Where some see feathers, Pableaux sees multiple generations of families. Where some see a parade, Pableaux sees the history of the city.”

— W. David Foster, Design and Internet Director for New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival

Photo by Pableaux Johnson

“I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Mr. Pableaux Johnson for his incomparable courage and commitment to the New Orleans Mardi Gras Indian Culture . . . [Pableaux] has had a lasting impact on the individuals and community that he has photographed over the years . . . .[H]is interpersonal skills and personality enhance his ability to interact with the culture and maintain a great respect for the secrecy and rituals of the Mardi Gras Indians.”

— Big Chief Tyrone Casby, Mohawk Hunters

Flagboy K9 (Alphonse Feliciana of the Golden Blades Tribe) at Big Chief Larry Bannock’s funeral second line in 2014.

Photo by Pableaux Johnson

These photographs are intimate, visceral, and charged with life, but they are also consistently executed with a high degree of visual sophistication . . . Mr. Johnson’s work is clearly an invaluable and indelible archive of photographs about a singular cultural contribution to this country, and as such should be celebrated and supported whenever and wherever possible.”

— Dawoud Bey, photographer and Professor of Photography/Distinguished College Professor at Columbia College Chicago

Pableaux Johnson (1966-2025) was a food writer and photographer raised in New Iberia and based in New Orleans. In addition to his four books on New Orleans cooking and other writing, Johnson is remembered for the weekly red beans and rice dinners he hosted and his photographs of New Orleans cultural events like second lines and Black Masking Indians.