Spring 2011

Lincoln in Louisiana

In 1828 and 1831, a young Abraham Lincoln would visit New Orleans by way of a flatboat journey down the Mississippi River. He was nearly killed on his first excursion.

Published: February 12, 2015

Last Updated: April 8, 2019

In 1828, a teenaged Abraham Lincoln guided a flatboat down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. The adventure marked his first visit to a major city and exposed him to the nation’s largest slave marketplace. It also nearly cost him his life, in a nighttime attack in the Louisiana plantation country. That trip, and a second one in 1831, would form the two longest journeys of Lincoln’s life, his only visits to the Deep South, and his foremost experience in a racially, culturally, and linguistically diverse urban environment.

Winter never fully arrived in 1828. Temperatures remained in their autumnal range, often rising to balminess and only occasionally dipping to seasonality or below. Rain fell from persistently cloudy skies, raising the waters of the Ohio and Mississippi. Trees greened prematurely; delighted farmers assumed an early spring and sowed seeds accordingly. Word from Louisiana had it that ears were growing on Indian corn—in February!—while harvestable bolls blossomed on Mississippi cotton plantations. “[E]very thing presents an appearance of June on the banks of the Mississippi,” marveled one Louisiana paper, even as it fretted about the river “attain[ing] a height that is truly alarming….” The Ohio had already exceeded its banks and flooded Shawnee Town in Illinois with six feet of water. Bad news for most folks, but good news for boatmen like Allen Gentry and Abraham Lincoln: high water meant swift sailing to New Orleans. First, however, they needed to build a flatboat.Abe certainly possessed the construction skills: he “was thoroughly master of all the phases of frontier life,” reported a neighbor, including “woods craft” learned from his father.

The construction site was probably at Gentry’s Landing, a hundred-acre wooded parcel downriver from the Rockport, Indiana bluff. This area afforded timber, space, and a good spot to launch. Abe certainly possessed the construction skills: he “was thoroughly master of all the phases of frontier life,” reported a neighbor, including “woods craft” learned from his father.

The size of the Gentry-Lincoln flatboat may be estimated by an 1834 journal describing a flatboat launched from nearby Posey County. It measured eighty feet long and seventeen feet wide (1,360 square feet), manned by five men. A crew of two could typically handle a vessel roughly half that size, 40 or 45 feet long by 15 or so feet wide. Construction usually took one to two months, depending on the number of helpers and the availability of milled wood. (Hand-hewing significantly slowed down work, but also lowered costs.) Most Indiana men possessed basic carpentry skills and flatboat experience, making workers easy to find. Total costs typically ranged around one dollar per length-foot, but were probably minimal for this two-man homemade enterprise.

Exactly when Allen Gentry and Abraham Lincoln launched their flatboat from Rockport is a critical piece of information, because it directs us to the proper time window in which Lincoln would have arrived in New Orleans and thus enables us to reconstruct the daily city life to which he was exposed. While 100 percent of the historical evidence points to either an early springtime launch or a late-autumn/early-winter launch in the year 1828, neither alternative can be proven by primary historical documentation. There are no registries, no receipts, no contracts, and certainly no journals nailing down the date. But other sources of evidence and clues abound, and they support of the spring hypothesis. Allan Gentry’s wife Anna said so clearly in an 1865 interview, and neighbors Absolom Roby and John Romine concurred. Lincoln himself left behind clues that buttress the springtime launch, and said or phrased or implied nothing to contradict it. Numerous strands of contextual evidence lend additional support to a spring departure, as do the invitingly high river stages of spring 1828 and the extremely large number of flatboat landings documented in the New Orleans Bee and Argus newspapers.

We must now attempt to refine exactly when in spring 1828 Gentry and Lincoln departed. March is too early: despite some support in the historical record, this month has a demonstrably small time window in which to prove correct. May or June, on the other hand, are too late. This leaves April, as evidenced by Anna Gentry’s clear recollection of an April-to-June trip. When in April? A killer frost on April 5–7 suddenly ended the “False Spring” of 1828, plunging temperatures by forty degrees into the teens “accompanied with a light Snow.” Presumably the duo would have waited out that wintry blast. By April 12, afternoon temperatures hit the 80s F. Did they leave then? Anna Gentry drops a clue in her interview with Herndon:

One Evening Abe & myself were Sitting on the banks of the Ohio or on the [flat]boat Spoken of. I Said to Abe that the Moon was going down. He said, “Thats not so—it don’t really go down: it Seems So. The Earth turns from west to East and the revolution of the Earth Carries us under, as it were: we do the sinking…The moons sinking is only an appearance.

Only a young crescent moon sets in the evening sky, one to three days after the new moon. In April 1828, the new moon occurred on April 14, thus young crescents would have set in the early evenings of April 15–17. Lacking any further clues and in light of the above evidence, this researcher posits that Allen Gentry and Abraham Lincoln poled out of Rockport, Indiana, around Friday or Saturday, April 18 or 19, 1828.

We must address a few other questions before reconstructing the voyage. First, what was their cargo? Amateur flatboat operations in this region carried the standard potpourri of Western produce—corn, oats, beans, pork, beef, venison, livestock, fowl, lumber, hemp, rope, tobacco, whiskey—sacked and barreled and caged and corralled and piled and bottled in organized chaos. Among boatmen, this was known as “mixed cargo,” as opposed to the “straight cargo” (single commodity) favored by large professional flatboat enterprises. Informants interviewed in 1865 remembered Lincoln had “[hauled] some of the bacon to the River”—smoked hog meat, in preparation for the voyage. A neighbor recalled buying pigs and corn from the Lincolns, leading one researcher to posit that the cargo probably comprised the two premier agricultural commodities of the region, “hogs and hominy.” Gentry family memories, recorded in the 1930s, cite “hogs” and typical Indiana “summer crops” as their ancestors’ standard flatboat cargo. Another family story, reported by 72-year-old E. Grant Gentry in 1936, claimed the flatboat carried “pork, corn in the ear, potatoes, some hay (was not a regular hay boat), and kraut in the barrel; apparently there were no hoop poles or tobacco….” Lincoln himself dropped a clue: “The nature of part of the cargo-load, as it was called,” he wrote in 1860, “made it necessary for [us] to linger and trade along the Sugar coast” of Louisiana. What might have been the nature of their cargo, that it would have traded better at the sugar plantations below Baton Rouge than in New Orleans proper? E. Grant Gentry testified that “the cargo was destined for…sugar planters who owned mules and negro slaves, the corn and hay being bought for the mules and the meat and potatoes for the slaves.” The cargo may well have included “barrel pork” (as opposed to bulk pork), which Southern planters demanded as a low-cost, high-energy food for slaves. Plantation caretakers constantly required a wide range of Western produce to maintain their village-like operations, and exchanged them for cotton or sugar, which flatboatmen thence carried downriver. One 1824 report, for example, explained that flatboats navigated “from the Ohio, down the Mississippi to New Orleans, touching at the small towns in their way, and if possible disposing of a part of their multifarious cargo.” Thus Lincoln’s Sugar Coast clue may not mean too much, except that it rules out straight cargo (by referencing “part of the cargo-load”). After “lingering” along the coast, flatboats would then proceed on to New Orleans, where buyers for the standard commodities of cotton and sugar abounded. We know for certain that the cargo belonged to the Gentry family, and by extension to Allen Gentry; Abraham was merely a hired hand earning a set wage.

“[O]ne night they were attacked by seven negroes with intent to kill and rob them. They were hurt some in the melee, but succeeded in driving the negroes from the boat, and then ‘cut cable’ ‘weighed anchor’ and left.” —Abraham Lincoln

Second, did they travel at night? Nocturnal navigation could add thirty or more miles to daily progress. It also risked perils, especially given the high, fast waters of spring 1828. Both men would have needed to be at the ready with steering oar and pole all night, allowing no time for sleep. We know for certain no one else helped: “[I] and a son of the owner,” wrote Lincoln in 1860, “without other assistance, made the trip.” Given that neither man ranked as expert pilot—this was Gentry’s second trip and Lincoln’s first—the duo probably resigned themselves to tie up at night. Flatboatmen minimized the lost travel time by launching pre-dawn, landing after sunset, and taking advantage of moonlight whenever possible.

Third, at what velocity did Gentry and Lincoln travel? Flatboats generally floated at the speed of a brisk walk or jog, depending on river stage and their navigational trajectory within the channel. High springtime waters meant a steeper gradient to the Gulf and flow rates of five or six miles per hour or more. When the river ran low (late summer through early winter), flow rates dropped to half or two-thirds the springtime pace. But 1828 water levels ranked exceptionally high and swift. A report field from St. Francisville, Louisiana, on March 8 stated that

[t]he Mississippi river is now from 2 to 4 inches higher at this place than comes within the memory of man…. As the river is still rising, and as the highest flood is rarely ever earlier that the end of April, may we not yet see it this spring as high as it was in 1780…when…it was at least three feet higher than it now is…? Two crevasses have [already] been made at Point Coupee….

This level roughly equates, according to modern-day measurements, to surface velocities averaging 5.2 to 6.0 miles per hour, and peaking at 6.7 to 7.9 miles per hour. Friction and occasionally strong headwinds would reduce this speed somewhat, such that we may reasonably assume a 5.5-mile-per-hour flatboat speed for the springtime launch scenario. If we assume twelve hours of travel per day (daylight in this region and season lasts thirteen to fourteen hours, minus time for launching, docking, problems, and other stops), we estimate progress at around 66 miles per day.

Gentry’s Landing at Rockport, lying between river miles 857 and 858 as enumerated from Pittsburgh, marked mile zero for Allen Gentry and Abraham Lincoln as they poled their flatboat into the gray Ohio River dawn, around Friday or Saturday, April 18–19, 1828. They launched carefully into the Ohio’s tricky “riffles” (ripples), something that Lincoln would later describe as a key skill for successful navigation. Within hours, he expanded his personal geography, laying eyes on terrain he had never seen before. The free North lay to their right; the slave South to their left. Gentry, the veteran, probably took pride in pointing features out to his friend. While the arctic blast two weeks earlier had killed nascent vegetation, forests and fields were now rejuvenating with new life, and it looked beautiful.

Danger lay below the beauty. Islands with sandy-bottomed aprons could trap a loaded flatboat beyond the capacity of two men to free it. Experienced boatmen watched for them assiduously—even in high water, which tended to mask and relocate obstacles, more so than eliminate them. Along with large towns, major confluences, prominent topographic features, and distinctive structures, islands served as mile markers and metrics of trip progress.

As April drew to a close, Gentry and Lincoln, unbeknownst to them, entered Louisiana waters. The Mississippi by this time finally ceased rising; still extraordinarily high and swift, the river would fall slightly by about eight inches during the remainder of their journey. The scenery remained undistinguished until shortly after the Yazoo River joined the Mississippi from the east, at which point a series of rugged hills and plunging ravines drew close to the river. Atop sat the community known by the Spanish as Nogales and by early Anglos as Walnut Hills (855th mile of the journey, 591st down the Mississippi, around April 30–May 1), until the Vick family and others from the New Jersey region settled there in 1820. By 1828, the well-situated city of Vicksburg commanded that lofty perch over the Mississippi. Conceivably it created a lasting mental image upon which Lincoln could draw thirty-five years later, when the fate of the nation rested in part on military action under his command here. Vicksburg’s landing, like most others, lay partially underwater in the spring of 1828.

With the wilderness of the inland delta behind him, Abraham Lincoln was now entering the heart of the Slave South for the first time in his life. He witnessed it from a river-landing perspective, and most assuredly saw numerous slaves in transit and in the fields well before arriving at New Orleans.

While professional flatboatmen with clients in New Orleans had no choice but to beeline to their big-city agents, amateur or speculative expeditions often traded en route. Some “worked the river” in methodical steps—loose cable, float downstream, pole in, drop anchor, tie-up, haggle, sell, loose cable—repeatedly, from plantation to village and onward. One flatboatman made “some eight trips down the Mississippi…selling produce at all the points from Memphis to New Orleans.” Trading before reaching New Orleans offered certain advantages. It put hard cash in pockets right away. It could also dramatically shorten the expedition, saving time and expenses while minimizing risk. But trading en route could also yield lower prices and weaker profits. And it eliminated the long-awaited chance to “see the elephant” and partake of New Orleans’ delights. Some flatboatmen got the best of both worlds by selling upcountry produce en route, re-filling the vacated deck space with locally gathered firewood or Southern commodities such as cotton and sugar, then proceeding to sell them in New Orleans.

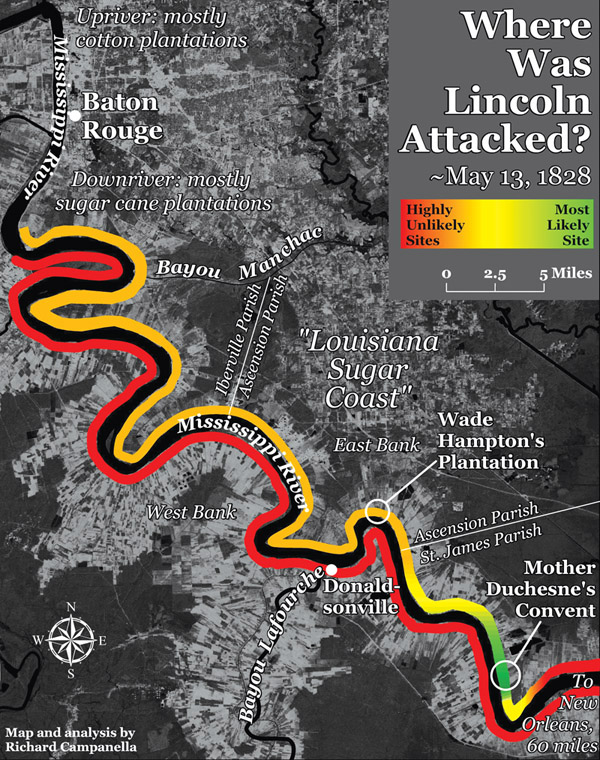

Richard Campanella identifies the area mapped in green tones, on the east bank of the Mississippi near the present-day town of Convent, as the most likely site of attack upon Lincoln. The site is a few hundred feet upriver from present-day St. Michael’s Church.

Gentry and Lincoln drew closer to the world of high culture as they approached the unquestioned queen of the Mississippi bluff cities: Natchez. They arrived around May 2–3, two weeks after departure, 959 miles into their journey and 695 miles down the Mississippi. Established as Fort Rosalie in 1716 by the same man (Bienville) who founded New Orleans two years later, Natchez rose by the early 19th century to rank among the most important and wealthiest enclaves in the Southwest. By the time Lincoln arrived in 1828, the city had recovered from a series of devastating epidemics, and was poised for an era of economic and urban expansion. Flatboatmen approaching the city would catch sight of magnificent new lighthouse mounted atop light-colored earthen cliffs “clothed with clouds of foliage,” set among the spires and rooftops on the 200-foot-high hill. Their world, however, awaited them at the landing—“Natchez Under the Hill,” as it has long been called—where, according to a mid-1830s observer,

several hundred flatboats lined the levee, which was piled for two thirds of a mile with articles of export and import, the stores were crowded with goods and customers, and the throng was as dense as that in the busiest section of New Orleans.

Others pondered the irony of the Great Emancipator nearly perishing at the hands of the very people he would later liberate, and wondered if some attackers survived long enough to be freed by their victim.

Poling out of Natchez set Gentry and Lincoln on the final 300-mile stint of their 1300-mile journey. Pebble-bottomed tributaries such as St. Catherine’s Creek and the Homochitto River intercepted their passage on the hilly Mississippi side to the east, while bottomland forest and the occasional cotton plantation dominated the flat Louisiana side to the west. Fort Adams, a military outpost dating to colonial times and now a small settlement, marked roughly the thousandth mile since their Rockport launch. A few miles later they passed the famous 31st Parallel, a former international border that now demarcated the Mississippi /Louisiana state line. They were now entirely in Louisiana. Straight west of that invisible demarcation, muddy water borne in the Rocky Mountains of Mexico (New Mexico today) flowed in from the Natchitoches plantation region. This was the Red River, the last major tributary from the western side of the valley to join the Mississippi.

Immediately below the Red River lay a confusing and potentially dangerous fork. “Be careful that you keep pretty close to the left [eastern] shore from Red river,” warned The Navigator, to avoid being drawn into this current, which runs out on the right shore with great rapidity. This is the first large body of water which leaves the Mississippi, and falls by a regular and separate channel into the Gulf of Mexico.

This was Bayou Chaffalio, today’s Atchafalaya River, the first distributary (that is, water flowing out of the main channel) of the lower Mississippi. Steering into the east prong of the fork, the men’s attention would have been caught by an “astonishing bridge” of trees, branches, and debris drawn out of the Mississippi by the Atchafalaya’s current. So dense and matted was the logjam—at the 1,032nd mile of the trip, 768th on the Mississippi, reached May 3–4—that “cattle and horses are driven over it.” The eighty-mile-long Red River Raft wreaked hydrological havoc on the area’s ecology under normal conditions, let along during high water. By one 1828 estimate, “the enormous quantity of brush, trunks of trees, &c…[had] gained at least one mile per annum;” and “back[ed up] the water upon the land for many miles,” making “a lake of what was before a prairie. The forests too…are often killed by the overflow of water, and after standing for a few years with their roots, submersed, the trees become rotten and fall,” thus worsening the blockage. The logjam also frustrated economic interests in the Acadian (Cajun) and Red River regions, by limiting direct navigational access to points south. To a problem-solving mind, the situation cried out for intervention.

Navigation interests on the Mississippi were additionally frustrated by the circuitous Old River meander, which lengthened travel time by hours. Rivermen hoped someday to avoid this loop by excavating the so-called Great Cut-Off across a swampy five-mile neck that separated the two yawning meanders (as occurred naturally in 1722 at nearby False River). Over the next decade, the Old River cut-off would be excavated and the Red River logjam would be cleared. Both internal improvements tremendously aided river interests and economic development, but also instigated a sequence of hydrological processes that would seriously threaten southeastern Louisiana and New Orleans a century later.

The busy little port of Bayou Sara, named for one of the last significant tributaries draining into the Mississippi, formed another “under-the-hill” landing typical of the east-bank bluffs below Vicksburg. Bayou Sara’s higher inland section was actually a separate town, St. Francisville, known for its serene beauty and the prosperity of the surrounding West Feliciana cotton country. This undulating region deviated from the rest of southern Louisiana in that English-speaking Anglo-American Protestants predominated over Franco-American Creoles and Acadians. The opposite was the case on the flat western side of the river, the Point Coupée region, which represented Gentry’s and Lincoln’s first encounter with an extensive, century-old Francophone Catholic region in Louisiana. The physical, cultural, and agrarian landscape changed along with the ethnic makeup, as The Navigator explained in 1814:

Here commences the embankment or Levee on the right [western] side of the river, and continues down to New Orleans, and it is here where the beauty of the Mississippi and the delightful prospect of the country open to view. [The banks from here], and from Baton Rouge on the left side down to the city of Orleans, have the appearance of one continued village of handsome and neatly built…frame buildings of one story high…stand[ing] considerably elevated on piles or pickets from the ground, are well painted and nicely surrounded with orange trees, whose fragrance add much delight to the scenery.

Another observer described the French Louisiana sugar manors as “large square edifices with double piazzas, and surrounded by orange and other evergreen trees [and] the extensive brick ‘sucriene’ or sugar house.” This arrangement differed from the “unpretending cottages [with] the humble wooden ‘gin’” of the Anglo-Louisiana cotton landscape on the eastern side of the river. That latter environment petered out at Port Hudson—last of the bluff landings—and at nearby Profit’s Island, the penultimate of the pesky atolls. The topography to the east now tapered off from bluffs with white-faced cliffs to low forested terraces, drained by the very last tributary of the Mississippi Valley, Baton Rouge Bayou. Below this stream sat the small city with that circa-1699 name, still years away from becoming the capital of Louisiana. Baton Rouge did, however, host the United States Barracks, a recently erected complex of five two-storied structures arranged in the shape of a pentagon, serving officers and soldiers deployed to the Southwest under the command of Lt. Col. Zachary Taylor. With pearl-white classical columns gleaming on the terrace, the Barracks regularly caught rivermen’s attention.

It is no exaggeration to say that Lincoln came very close to being murdered in Louisiana.

An intriguing legend posits that Lincoln did more than merely gaze at the Barracks from afar. The story seems to have originated with college professor and Confederate veteran Col. David French Boyd, who served as president of Louisiana State University when the institution occupied the decommissioned Barracks in the late 1800s. Boyd perused old garrison papers and recorded the notable military figures listed as visitors, among them the Marquis de Lafayette, Ulysses S. Grant, Robert E. Lee, Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, George A. Custer, and others. Boyd claimed to have identified two other famous names in the papers, each denoted as “civilian” and undated. One was Jefferson Davis; the other was Abraham Lincoln. If true, the record would form the only surviving first-hand vestige of Lincoln in Louisiana. This researcher has been unable to find the “garrison records” that Boyd inspected and thus cannot verify his claim. Intuition, however, works against it. The notion of an anonymous poor young flatboatman visiting a restricted military facility, signing in, and perhaps even spending the night seems highly improbable, not to mention inexplicable. Why would he leave the flatboat? Why would he even approach the barracks, and why would the guards allow the ill-clad youth in? Even if Boyd correctly identified Lincoln’s name, it does not follow that Lincoln visited the Baton Rouge Barracks. Both Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis served in the Blackhawk War (1832), as did former barracks commander Zachary Taylor. War records might have gotten mixed up with barracks records.

After departing Baton Rouge around May 4, Gentry and Lincoln floated out of the alluvial valley of the Mississippi River and entered its deltaic plain. No longer would “hills (like the oasis of the desert) relieve the eye of the traveller long wearied with the level shores,” as one visitor described the topographical transition. The banks—called natural levees—now lay above the surrounding landscape, forming the region’s highest terrestrial surfaces; cypress swamp, saline marsh, and salt water lay beyond. The Mississippi River in its deltaic plain no longer collected water through tributaries but shed it, through distributaries such as bayous Manchac, Plaquemine, and Lafourche (“the fork”). This was Louisiana’s legendary “sugar coast,” home to plantation after plantation after plantation, with their manor houses fronting the river and dependencies, slave cabins, and “long lots” of sugar cane stretching toward the backswamp. The sugar coast claimed many of the nation’s wealthiest planters, and the region had one of the highest concentrations of slaves (if not the highest) in North America. To visitors arriving from upriver, Louisiana seemed more Afro-Caribbean than American, more French than English, more Catholic than Protestant, more tropical than temperate. It certainly grew more sugar cane than cotton (or corn or tobacco or anything else, probably combined). To an upcountry newcomer, the region felt exotic; its society came across as foreign and unknowable. The sense of mystery bred anticipation for the urban culmination that lay ahead.

But Allen Gentry and Abraham Lincoln were here for business, not touring. Like other flatboatmen, they decided—or more likely, had been instructed by James Gentry—to remove their piloting hats at this point of the journey and don their salesmen hats. Lincoln himself stated that, during his “first trip upon a flat-boat to New-Orleans…[t]he nature of part of the cargo-load…made it necessary for [us] to linger and trade along the Sugar coast.” Flatboatmen would pole along the slackwater edge of the river, drop anchor, “cable up” at the plantation landing, inquire for the manager, and offer to trade. “We are now in the sugar belt,” wrote one flatboatmen upon reaching the same region; “[t]he river is always dotted with up-country boats, sometimes a score being in sight at once.” They shared the banks with washerwomen, water-retrievers, fishermen—and a sight that startled one particular traveler of this same era:

I was surprised to see the swarms of children of all colours that issued from these [plantation] abodes. In infancy, the progeny of the slave, and that of his master, seem to know no distinction; they mix in their sports, and appear as fond of each other, as the brothers and sisters of one family….

After lingering and trading along the sugar coast for a roughly a week (starting, in this estimated chronology, around May 5), Gentry and Lincoln tied up for the evening of May 12 or 13 approximately sixty miles above New Orleans. That night would prove to be the most memorable, and dangerous, of Lincoln’s entire river career.

Using his characteristic brevity and speaking of himself and Gentry in the third person plural, Lincoln recalled many years later what happened next:

[O]ne night they were attacked by seven negroes with intent to kill and rob them. They were hurt some in the melee, but succeeded in driving the negroes from the boat, and then “cut cable” “weighed anchor” and left.

Biographer William Dean Howells offered a compatible account of the incident, worth quoting because Lincoln personally reviewed Howells’ draft and tacitly validated that which he did not edit:

“One night, having tied up their ‘cumbrous boat,’ near a solitary plantation on the sugar coast, they were attacked and boarded by seven stalwart negroes; but Lincoln and his comrade, after a severe contest in which both were hurt, succeeded in beating their assailants and driving them from the boat. After which they weighed what anchor they had, as speedily as possible, and gave themselves to the middle current again.

Neighbors interviewed by William Herndon in 1865 readily recalled the incident, suggesting that Gentry and Lincoln featured it in fireside stories about their New Orleans adventure. “Lincoln was attacked by the Negroes,” recalled neighbors;

no doubt of this—Abe told me so—Saw the scar myself.—Suppose at the Wade Hampton farm or near by—probably below at a widow’s farm.

Anna Gentry shed more light on the incident, which her spouse Allen experienced firsthand:

When my husband & L[incoln] went down the river they were attacked by Negroes—Some Say Wade Hamptons Negroes, but I think not: the place was below that called Mdme Bushams Plantation 6 M below Baton Rouche—Abe fought the Negroes—got them off the boat—pretended to have guns—had none—the Negroes had hickory Clubs—my husband said “Lincoln get the guns and Shoot[”]—the Negroes took alarm and left.

John R. Dougherty, an old friend of Allen Gentry whom Herndon interviewed on the same day as Anna, corroborated her details with first-person knowledge of the site:

Gentry has Shown me the place where the niggers attacked him and Lincoln. The place is not Wade Hamptons—but was at Mdme Bushans Plantation about 6 M below Baton Rouche.

Dougherty was not the only Lincoln associate with personal connections to the site; Lincoln’s cousin John Hanks claimed to be in the vicinity when the attack occurred in 1828. “I was down the River when Negroes tried to Rob Lincoln’s boat,” he told Herndon in 1865, but “did not see it.”

Dougherty was not the only Lincoln associate with personal connections to the site; Lincoln’s cousin John Hanks claimed to be in the vicinity when the attack occurred in 1828. “I was down the River when Negroes tried to Rob Lincoln’s boat,” he told Herndon in 1865, but “did not see it.”

Where exactly did the Louisiana incident occur? We have three waypoints to triangulate off: (1) a plantation located below Wade Hampton’s place, specifically one (2) affiliated with a woman named “Busham” or “Bushan,” (3) located around six miles below Baton Rouge. Wade Hampton’s sugar plantation remains a well-known landmark today, marked by the magnificent Houmas House in Burnside, which was built twelve years after the incident to replace the antecedent house. Just below the Hampton place, we seek a woman-affiliated plantation whose surname could only be remembered as sounding like “Busham” or “Bushan.” A parish census in 1829, the federal census of 1830, and detailed plantation maps made in 1847 and 1858 record no such surnames, nor a woman-led household in the specified location. But Herndon apparently gleaned additional information that did not appear in his interview notes, because when he published Herndon’s Lincoln in 1889, he reported “the plantation” belonging not to “Busham” or “Bushan,” but to the rhyming “Duchesne”—specifically “Madame Duchesne.” That surname, common in France but not in French Louisiana, also fails to appear in the aforementioned sources. The 1829 St. James Parish Census does list a Dufresne family (with nineteen slaves), but they do not align with our criteria. The 1830 federal census records only two Duchesne families throughout the entire region, both from New Orleans proper.

Yet there was a Duchesne woman affiliated with this area: French-born Rose Philippine Duchesne (1769–1852), who in 1825 founded the Convent of the Sacred Heart (St. Michael’s) in present-day Convent, located twelve miles below the Hampton Plantation. Duchesne established Catholic missions, orphanages, convents, and schools for the American branch of the Society of the Sacred Heart, focusing on the Francophone regions of St. Louis and South Louisiana. She became well-known and well-loved in those areas; people called her “Mother Duchesne,” and the institutions she founded became known as “Mother Duchesne’s convent,” “Mother Duchesne’s school,” etc., even if she did not reside there. (In fact, Duchense was on assignment in St. Louis when Gentry and Lincoln floated south, and was recorded by the 1830 census as residing in a convent in that Missouri city. ) Mother Rose Philippine Duchesne was canonized a saint by the Catholic Church in 1988; a shrine in St. Charles, Missouri entombs her remains today.

It is plausible that the property affiliated with the woman whose name sounded like “Busham,” “Bushan,” or “Duchesne” was in fact Mother Duchesne’s convent. Gentry and Lincoln may have heard that name from passersby or river traders, and reasonably assumed it was a plantation, notable because it was owned by a woman. The convent itself certainly resembled a large plantation house of the era (see photograph in graphical insert). Thus, Mother Duchesne’s convent, after thirty-seven years of Indiana storytelling, became “Mdme Bushans Plantation.” No other explanation has come to light.

We have one final problem in situating Lincoln’s Louisiana melee: Wade Hampton’s plantation is not located six miles below Baton Rouge, neither by terrestrial nor riverine measure—but exactly sixty river miles. Just as Indiana storytelling over many years may have converted “Bushan” to “Duchesne,” it also may have shifted “sixty” to “six.” It is worth noting that the countryside located six river miles below Baton Rouge lies only slightly beyond the cotton-dominant terraces and bluffs of the Mississippi River’s lowermost alluvial valley, and barely onto the sugar-dominant deltaic plain. Sixty miles below, however, brings one to the heart of the Louisiana sugar region. Given that Lincoln said he and Gentry “linger[ed] and trad[ed] along the Sugar coast” before the attack occurred, it sounds as though they were deep into sugar country, not recently arrived at its brink.

Allen Gentry and Abraham Lincoln had finally reached New Orleans, after 1,009 miles on the Mississippi and a grand total of 1,273 river miles since departing Rockport.

In sum, then, this researcher posits that Gentry and Lincoln were attacked near, of all things, a convent and girls’ school founded by a future American saint. We can say with greater confidence that the melee occurred within St. James Parish, sixty to seventy-two miles downriver from Baton Rouge, on the east bank of the river (as evidenced by all three of our waypoints: Baton Rouge, Hampton’s plantation, and Duchesne’s convent). Some biographers position the incident as having occurred near Bayou Lafourche and Donaldsonville, but those features sit across the river and a few miles above where all evidence indicates.

Who were the attackers? Numerical probability suggests they were slaves from a nearby plantation. Circumstances, however, imply they might have been runaways. Fugitive slaves were desperate for resources, and (arguably) more inclined to run the risk of stealing to survive. Apparently the attackers spoke English, since they understood Gentry’s holler to “get the guns,” and not a single source mentions French words flying. This suggests the men were “American” slaves, as opposed to the French-speaking Creole slaves who predominated on the sugar coast—thus making the fugitive theory slightly more plausible. (Only a few days after the incident, the local sheriff jailed three medium-build “American negro” men, ages 24–32 and speaking English only, who were in St. James Parish “without any free papers.” )

Legions of Lincoln biographers have imparted dramatic detail into the tussle. Others pondered the irony of the Great Emancipator nearly perishing at the hands of the very people he would later liberate, and wondered if some attackers survived long enough to be freed by their victim. Retellings in modern-day articles and travelogues often de-racialize the incident, describing the attackers as “seven men.” Others ignore it altogether, perhaps for the inconvenient twist it inflicts upon the traditional black-victimhood narrative associated with Lincoln’s New Orleans experience. One writer took another tactic, explaining, with zero evidence, that the thieves were really “half-starved slaves of a no-good plantation owner,” and went so far as to fabricate Lincoln saying, “I wish we had fed them instead of fighting them….their owner is really more to blame than they,” despite Lincoln’s actual testimony of their lethal intentions.

On a different level, the incident provides insights into the nature of race relations and slavery in this time and place. Blacks attacking whites contradicts standard notions about the rigidity of racial hierarchies in the antebellum South—a hierarchy that, particularly in the New Orleans area, was more rigid de jure than de facto. On an ethical level, one may view the incident as producing not seven culprits and two victims, nor vice versa, but rather nine victims—victims of the institution of slavery and the violent desperation it engendered. On a practical level, we learn from the incident two details on the flatboat voyage itself: that the men traveled unarmed, and that they indeed avoided nocturnal navigation by tying up at night.

Some say Lincoln received a lasting scar above his right ear from the fight; others say the wound landed above his right eye, although one is not readily apparent in photographs. One informant said Lincoln specifically showed him the scar. The memory of the incident certainly lasted a lifetime, and that is perhaps the most significant message we can take away from this episode: according to Lincoln’s public autobiographical notes, the attack, and not slavery or slave trading, formed the single most salient recollection of both his Louisiana voyages. (Private statements were a different matter; more on this later.) It is no exaggeration to say that Lincoln came very close to being murdered in Louisiana. The incident may also underlie an unverified story that Lincoln acquired during his New Orleans trip “a strange fixation—that people were trying to kill him.”

Nursing their wounds, the shaken and bloodied men made off in the darkness and continued downriver. The rising sun revealed plantation houses—some modest, some palatial—fronting both banks at a frequency of eight or ten per mile and set back by few hundred feet from what one traveler described as the river’s “low and slimy shore.” Lacking topographic landmarks, rivermen used planters’ houses as milestones: Bayley’s, Arnold’s, Forteus’, Barange’s—“said to be the handsomest on the river.” Surely Gentry and Lincoln saw the ubiquitous lines of whitewashed slave cabins behind each planter’s residence (levee heights were far lower than they are now), but they may not have seen multitudes of slaves in the cane fields. At this time in May, Louisiana sugar cane began to develop “joints” and required little field labor until “October or November, when they cut, grind and boil the cane….”

As Gentry and Lincoln steered downriver, the passing parade of plantation houses occasionally gave way to clusters of humble cottages. Then the parade resumed, in layered sequence: manor house in front of dependencies and sheds, in front of slave cabins, in front of cane fields, with oaks, fruit orchards, and gardens on either side. Church steeples punctuated the riverside landscape: Contrell’s Church and Bona Cara [Bonnet Carre] Church marked the 942nd and 960th mile down the Mississippi, while the oft-noted Red Church (978th mile) lay halfway between the distinctive West Indian–style double-pitched roofs of the colonial-era Ormond and Destrehan plantations (both of which still stand). Simple wooden cottages appeared in isolation amid fenced gardens—then in greater densities, then merging into contiguous villages, separated by fewer and fewer agrarian expanses. Shipping traffic increased; more and more Gentry and Lincoln found themselves dodging and evading other vessels. Malodorous and noisy operations—steam-powered saw mills, sugar refineries, distilleries, soap factories, tallow chandlers (renderers of animal parts for candle-making)—indicated a proximate metropolis. A cacophony of distant whistles, shouts, bells, horns, hoof beats, and hammer blows carried across the 2,000-foot-wide river, growing ever louder. Long brick warehouses for tobacco and cotton came into view, some pressing cotton lint with horse or steam power.

Finally, in the midst of one particularly spectacular meander, a great panoply of rooftops arose on the left horizon. Sunlight glistened off myriad domes and steeples, amid plumes of steam, smoke, and dust. Allen Gentry and Abraham Lincoln had finally reached New Orleans, after 1,009 miles on the Mississippi and a grand total of 1,273 river miles since departing Rockport. The same day that started all too early with the frightening nighttime attack in St. James Parish, ended with the springtime sunset bathing the Great Southern Emporium in a golden glow.

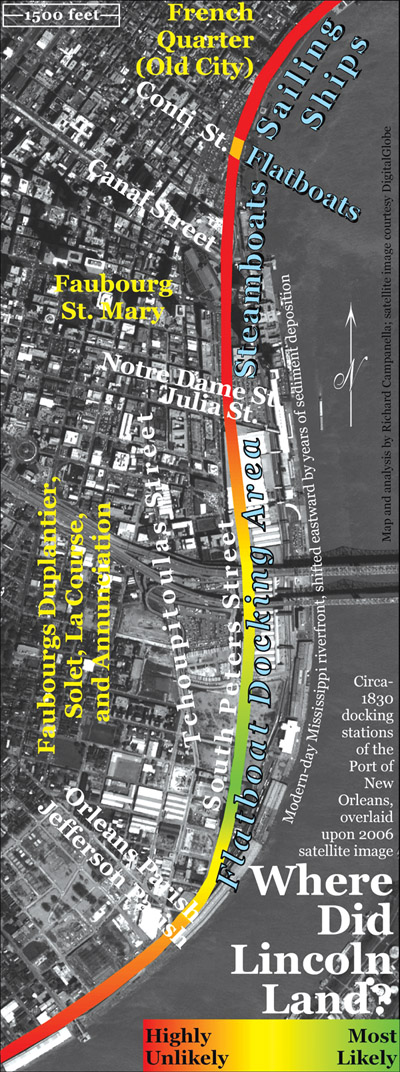

Veteran flatboatmen like Gentry knew where to go and what to do: steer into the current toward the upper end of that long thorny line of poles, masts, rigging, sails, and smokestacks. Silhouette of the great Western fleet, the bristling accoutrements belonged to local vessels like the bateau á vapeur (steamboat) Columbia departing for Bayou Sara, and to ocean-going sailing ships bound for Liverpool, Havre, and Bordeaux. Those craft crossed paths with the brig Castillo, pulling out for New York; the schooner Triton, bound for Charleston; and the Correo, destined for Tampico, Mexico. Outgoing vessels made room for the Mexican brigs Doris and Orono, bringing in passengers and Campéche wood from across the gulf, and the bateau de remorque (towboat) Grampus coming in from the mouth of the Mississippi. The hypnotic maneuvering—involving ships that Lincoln had previously seen only in drawings, bound for exotic destinations he knew only through books—played out less than a mile downriver from their destination. That stretch, the lowly uptown flatboat wharf, saw none of the spectacular sights and sounds of the downtown steamboat and sailing wharves, but bustled nevertheless with impatient pilots, flailing poles, tossed ropes, and hurled invectives. Gentry and Lincoln, as it turned out, picked a bad time to arrive: mid-May 1828 saw more flatboat arrivals (53) than any other ten-day period during the surrounding year, with the highest single-day total (28) being reported in the New Orleans Bee on May 17. Among those chalans docking with Gentry and Lincoln were ten from Tennessee and Alabama delivering cotton for local Anglo merchants, three from Kentucky with cotton and tobacco mostly consigned to local dealers, and fourteen small amateur operations like theirs, originating from various upcountry places.

Probability helps narrow down Gentry and Lincoln’s likely landing site. We can be nearly certain that they did not dock in the Old City. Some flatboats did land around the foot of Conti Street, but they specifically served downtown markets with fresh vegetables, fish, game, and firewood, rather than upcountry bulk produce. Instead, it was the uptown flatboat wharf that almost certainly received Gentry and Lincoln. A coveted slot near Notre Dame/Julia would have been unlikely, because professional merchant navigators running major flatboat operations tended to monopolize that valuable space. Greenhorn amateurs like Gentry and Lincoln probably settled for an easier uptown slot, toward Richard and Market streets. The most probable landing site lies somewhere among the open fields immediately south of the Mississippi River bridges, along South Peters Street near the Henderson intersection. On the bicentennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth, these fields lay vacant, weedy, and eerily silent.

—–

The preceding is an abridged excerpt from Lincoln in New Orleans: The 1828–1831 Flatboat Voyages and Their Place in History, by Richard Campanella (University of Louisiana Press, Lafayette, 2010). Please see the book for sources, footnotes, and further historical analysis.

Tulane geographer Richard Campanella is the author of Bienville’s Dilemma, Geographies of New Orleans, Time and Place in New Orleans: Past Geographies in the Present Day, and other books. He is the only two-time winner of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Book of the Year Award.