Summer 2017

Living Color

Ogden Museum of Southern art exhibitions showcase William Eggleston and his influence

Published: June 8, 2017

Last Updated: September 17, 2018

What Kramer and his compatriots did not realize was that the language of Eggleston and those who followed him—Stephen Shore, Joel Sternfeld, Richard Misrach—was two-fold in the way it pushed boundaries. By experimenting with various production techniques, such as Eggleston’s dye-transfer printing, and presenting portraits of the mundane and suburban, these “New American Color Photographers” permanently changed the landscape of photography as art.

Exhibitions at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art explored the richness of this changed landscape by showcasing major works by William Eggleston alongside other Southern photographers who can visibly trace the roots of their own art through the art of Eggleston: William Christenberry, Birney Imes, William Greiner, William Ferris, and Alec Soth.

William Eggleston: Troubled Waters (from the collection of William Greiner) was a glimpse into the photographer’s most prolific decade and favorite subject—summarized by Hilton Kramer as “dismal figures inhabiting a commonplace world of little visual interest”—which was roadside life in and around Memphis and the Mississippi Delta.

What Kramer found “perfectly banal,” Eudora Welty found “extraordinary, compelling, honest, beautiful, and unsparing” in her introduction to Eggleston’s The Democratic Forest, published in 1989. The photographs, Welty noted, “all have to do with the quality of our lives in the ongoing world: they succeed in showing us the grain of the present, like the cross-section of a tree. The photographs have cut it straight through the center.”

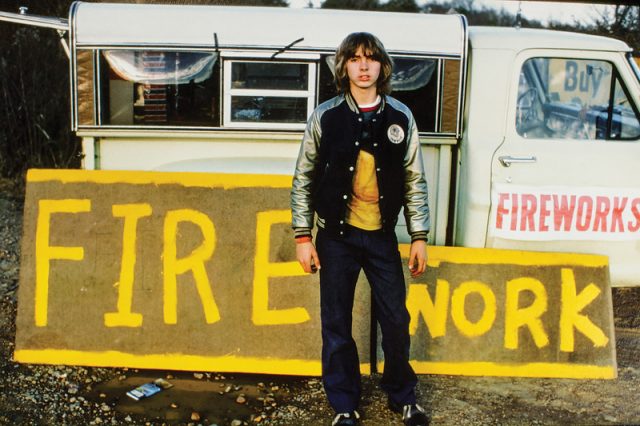

William Ferris, Unidentified Fireworks Salesman, Leland, MS, 1976. Archival pigment print. Courtesy of the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, Collection of William Greiner

In Troubled Waters, Eggleston has photographed what Welty eloquently called “every tell-tale thing we leave behind us.” A photograph taken looking down into a crowded freezer containing Swift’s vanilla ice cream, Kroger’s beef pie, and Frosty Acres’ Tasty Taters reminds the viewer of how color photography got its first kick—in advertising—but instead of selling the viewer on the products shot, the focus of the photograph is on the individual who owns the freezer, though there isn’t a human figure in sight. While people are absent from the majority of the portfolio, their absence is hardly noticed, because their lives are so clearly the subject of the photographs. In a shot of a vibrant landscape, tire tracks tell a rich story of the figures not in view; in a portrait of muddy puddles, a box of Quaker State oil drums and a crushed Coke can speak leagues of the individuals outside the frame.

In one of the strongest images in the collection, a soft yellow room contains a floral upholstered chair, a home organ holding a copy of Best Loved Hymns sheet music, and a small landscape painting framed on the wall. The corner of a white linen-covered couch and the edge of a burnt-orange padded settee are also visible. The photograph is at once too real, like something borrowed from the photorealists, and too intimate—something stumbled upon and too personal to look at, too private to linger on. However, Eggleston’s incredible grasp of color, light, and staging invites the viewer to stay and look.

It is this same mastery of color that links the photographers in the exhibition The Colourful South: William Christenberry, Birney Imes, William Greiner, William Ferris, and Alec Soth, which is opening alongside Troubled Waters. This exhibition explores the influence of each photographer upon one another and situates their work in a larger narrative of photography in the South after William Eggleston. Each a pioneer of color photography in his own right, these photographers show the viewer the same Southern world through various eyes. Each photographer has his own story to tell, and there is a clear narrative and cohesive aesthetic traced throughout the exhibition.

These two exhibitions presented a rare opportunity to see giants in a particular medium shown alongside the artist who helped establish that medium as a recognized art form. Similar landscapes are shown side-by-side—similar faces, similar rooms—and yet each is unique in its progression of the art form, and each invites a closer look.

William Eggleston: Troubled Waters (from the collection of William Greiner) and The Colourful South: William Christenberry, Birney Imes, William Greiner, William Ferris, and Alec Soth were on view at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art from June 10 to October 26, 2017.

Miriam Taylor is the communications manager for the Ogden Museum of Southern Art.