Local Stories, Global Industry

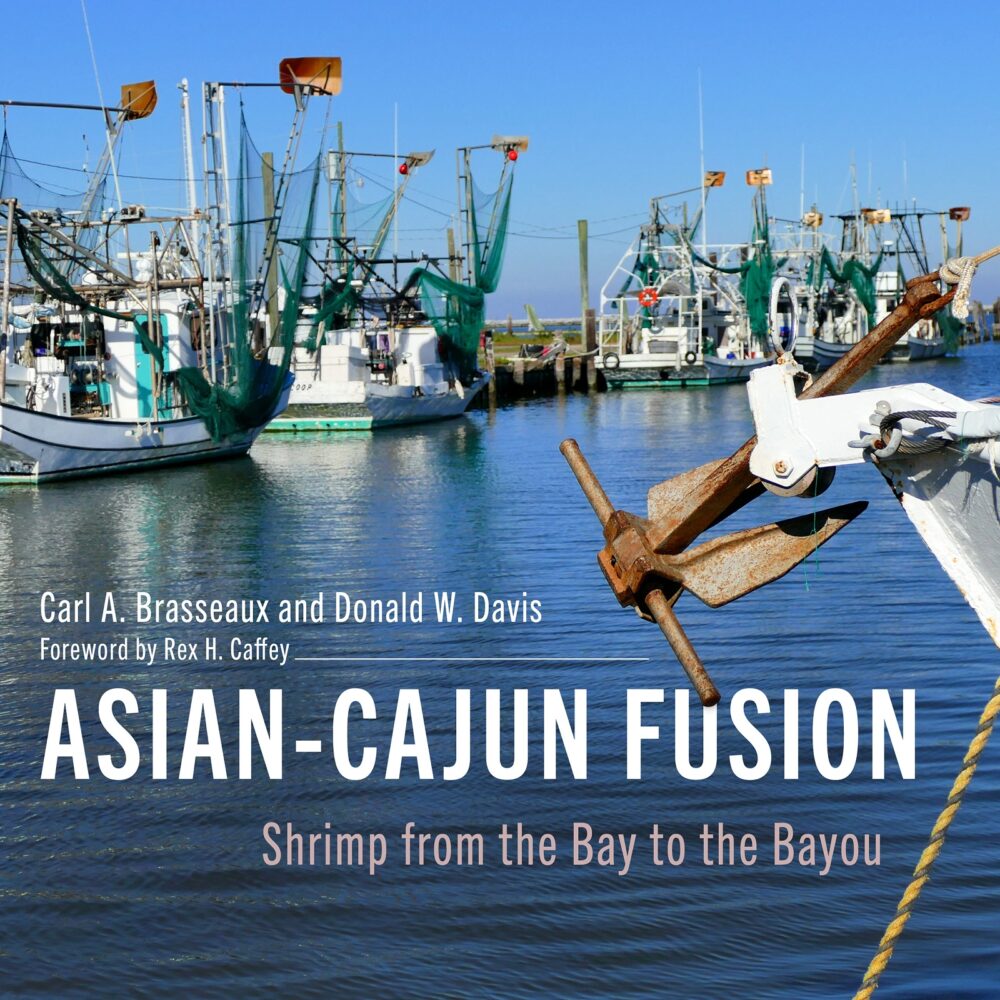

Asian-Cajun Fusion: Shrimp from the Bay to the Bayou by Carl A. Brasseaux and Donald W. Davis

Published: November 29, 2022

Last Updated: February 28, 2023

For Brasseaux and Davis, the story of shrimp in the Pelican State begins with the records of French colonial settlers who expressed disgust toward shrimp as “drunkards’ food.” (The authors omit any mention of shrimping practices within Indigenous communities.) The local reputation of shrimp began to change when a revolution in present-day Haiti caused the flight of refugees to New Orleans, doubling the population of the city and shifting the norms in culinary practices. When the Taiping Rebellion produced another wave of immigrants and refugees in the mid-nineteenth century, the Chinese community that settled in New Orleans brought with them shrimp-preserving techniques that are widely acknowledged as the origins of the modern shrimp-drying industry in the Louisiana bayou region. In such ways, Asian-Cajun offers a perspective not only commercial and technological but also sociocultural—how Louisiana shrimping has been shaped by world history.

It is clear that the history of Louisiana shrimping is also inescapably linked to racial hierarchy and labor exploitation. The Haitian refugees also consisted of white captors who sold or rented out enslaved workers whom they had brought with them to New Orleans, the Chinese immigrants were also coolies meant to replace the enslaved labor force after the American Civil War, a local Cajun working force only developed after xenophobic laws during WWI put an end to an exploitative institution of seasonal immigrant labor, and the revitalization of the Louisiana shrimping industry by Vietnamese refugees was a direct result of the American War in Vietnam. These facts continue to affect the racial landscape of Louisiana and the larger US today. It is a momentous contribution by Brasseaux and Davis to bring due attention to these forgotten contexts to the history of shrimp consumption.

At times, their sensitivity to racial difference falls short. The authors come across as retrograde when they denote Asia as “the Far East” and refer to Vietnamese refugees as “boat people.” Meanwhile, they flatten the differences between Chinese and Vietnamese communities for the sake of drawing out what they regard as a continuous narrative momentum: “the Louisiana shrimp industry has come full circle. Asians introduced the commercial shrimp industry to the Bayou State in the late nineteenth century, and one hundred years later, the fishery began to recoup much of its lost Asian character.” Most frustrating of all, racial violence is neutralized as a type of cultural misunderstanding, and acts of white supremacy toward Vietnamese refugees are cloaked by the passive voice and a happy ending: “Guns were fired, boats were sideswiped, trawl nets were cut, and some boats and dwellings were burned. Over time … the Vietnamese were gradually integrated into the Louisiana shrimping industry.”

Today, the Louisiana shrimping industry faces tremendous challenges. As Brasseaux and Davis argue, this American industry is largely a victim of its own success: unable to keep up with the exploding demand that this local industry stimulated, shrimp production has now been overtaken by foreign markets that rely on aquafarms rather than capturing wild shrimp. Meanwhile, oil spills by multinational energy companies have devastated the delta’s ecosystem and created high levels of toxicity in seafood; hurricanes and the negligent response by the national government have incapacitated fisheries; coastal subsidence and global warming have not become any less of a threat; and the COVID pandemic has only intensified the struggles of Louisiana’s shrimpers, reminding us of how the story of this industry is and continues to be shaped by global sociocultural forces.

Asian-Cajun Fusion: Shrimp from the Bay to the Bayou reminds us that the national and global popularity of shrimp originates from this Louisiana-based industry, which the authors assert is more vulnerable than ever. The book is replete with incredible pictures, records, and other archival material focusing on the local and cultural dimensions of the development of shrimping along the state’s coast. As long as the reader remains mindful of the racial politics surrounding the authors’ sometimes dubious language, Asian-Cajun Fusion stands as a valuable account of the diverse and overlooked story of Louisiana shrimping.

Sydney Van To is a PhD candidate in the English Department at UC Berkeley, with research interests in Asian American literature and critical refugee studies. His writing has appeared in diaCRITICS, Asymptote, the Chicago Review of Books, and other publications.