Summer 2021

Local Vintage

Louisiana’s sweet citrus wine

Published: May 28, 2021

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

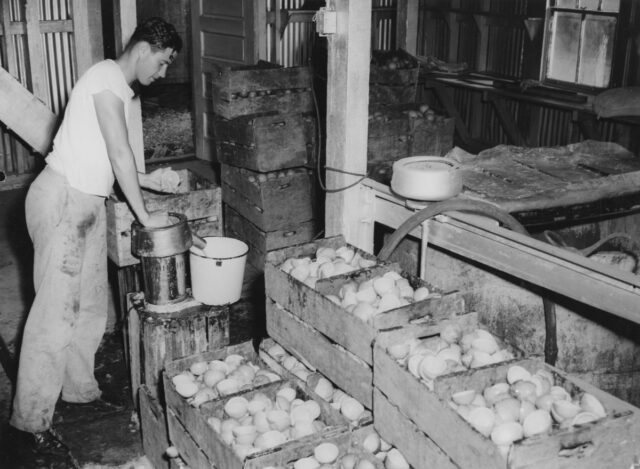

Photo by Gregory Theriot

“We have all kinds of sea food, sweet Louisiana oranges, and that delicious and delectable Louisiana orange wine,” read one 1937 advertisement for The Oyster Nook restaurant in the Shreveport Journal. The paper, along with others in Louisiana, ran ads for decades touting the beverage and cooking-column recipes relying on it, like a 1966 recipe for “Ducks à la Delacroix,” cooked with orange wine in a Dutch oven.

Orange wine is traditionally used to add flavor to poultry in Louisiana. “We started making it because so many people wanted it for cooking duck,” said Henry Amato, whose winery in Independence, Louisiana, is today the state’s only commercial orange wine producer. But it’s certainly also enjoyed as a beverage. “In our family, it was the tradition that when someone came to visit, you brought out the orange wine unless it was time for coffee,” said Randy Fertel, the son of Ruth’s Chris Steak House namesake Ruth Fertel and the nephew of onetime Port Sulphur orange wine maker Sig Udstad. “A little tumbler of orange wine was the family treat.”

The 1940s guidebook The Bachelor in New Orleans points to a “New Orleans Martini” that’s “made with Louisiana Orange Wine in place of vermouth” as being on offer in the city. The 1938 edition of Stanley Clisby Arthur’s Famous New Orleans Drinks and How to Mix ’Em explains that when it comes to an orange whiskey cocktail, “in some New Orleans homes the celebrated Louisiana Orange Wine, made in the orange groves below the city, is used in preference to the plain orange juice.” It can also simply be drunk on its own, especially around Thanksgiving and Christmas when oranges come into season. It’s sweeter than many popular grape wines and is often served chilled as a dessert wine or even poured over ice cream. The sweetness is thanks to the high sugar content of the oranges it’s made from, and that higher level of sugar also contributes to another distinctive property of the wine: a relatively high level of alcohol.

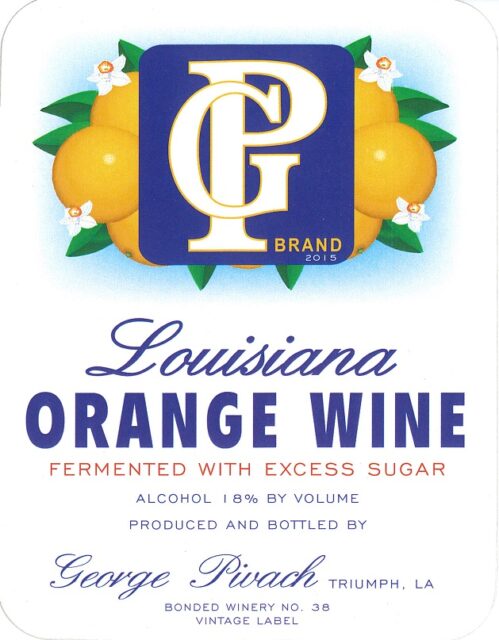

“It’s a sipping wine,” said George Pivach II, an attorney based in Belle Chasse whose family owned an orange winery through the 1960s. “You chug-a-lug it, you’re gonna wake up the next day with a big headache.”

Naturally, the wine’s potency has at times also been seen as an advantage. “Dog my cats! Have you tried our new orange wine?” asked an imagined speaker in a 1935 newspaper ad from the North Louisiana Beverage Company in the Shreveport Times. “… and how!” answered a second speaker, presumably representing a satisfied customer. “What do you suppose makes one grin like a Cheshire Cat?” The ad, offering gallons for $2.25 and fifths for 75 cents, cited the alcohol content at 20 percent. (Typical grape wine clocks in around 12 percent.)

In some parts of Plaquemines Parish, which has long been the citrus-growing capital of the state, orange wine was also an easy way to grin and bear Prohibition. It can be made with little more than oranges and yeast—for either home consumption or under-the-radar sales. Even the guide to Louisiana produced in the 1940s by the Works Progress Administration recalled that the small Plaquemines Parish community of Triumph was a “Mecca of wine lovers” and “the site of many small illicit wineries” during the nation’s dry period. In Fertel’s memoir The Gorilla Man and the Empress of Steak, he recounts a family story where Prohibition agents, having received a tip that the family was stockpiling wine, fired shotguns into the attic “until wine flowed down the walls.”

Some illicit Plaquemines orange wine likely made it across parish lines to New Orleans, even if not all of its consumers realized that’s what they were drinking. In 1930, newspapers reported that Prohibition agents rowed pirogues fifteen miles through Plaquemines Parish bayous to discover orange wine intended to be sold, presumably carbonated, in the city, and falsely labeled as Champagne. “What celestial use,” wrote New Orleans States columnist Meigs O. Frost in a comic poem, “for gallons of our morning orange juice!”

Citrus has been grown in what’s now Plaquemines Parish for centuries. Jesuit missionaries first planted citrus trees there in the early 1700s and commercial production started by the 1830s, according to a 1961 study by Georgia State College geographer Sanford H. Bederman. The parish is better suited than most of Louisiana to citrus production thanks to its warm climate, since sustained freezing temperatures can damage or even kill citrus trees. “Really anywhere north of I-10 it gets spotty,” said Jeb Fields, an assistant professor and extension specialist at the Louisiana State University AgCenter.

Citrus is also a point of pride for Plaquemines Parish. The parish has held a regular Orange Festival since 1947, crowning a festival king and queen while celebrating the local crop with events like orange eating and peeling contests. Nutrient-heavy soil deposited by the Mississippi River has helped local farmers grow juicy, sweet oranges, satsumas, and other citrus fruit, said James Madere, a local historian and former president of the Plaquemines Historic Association. “The land here is so rich from that topsoil,” Madere said. “The citrus here is much sweeter.”

In 1941, local civic boosters even offered one hundred gallons of orange wine to any other jurisdiction that produced an output as diverse as that of Plaquemines Parish, citing production of commodities like fruit, sugar cane, oil, and seafood. (Dry counties could opt instead to receive unfermented fruit.) Of those local industries, citrus farming was sometimes one of the more convenient for parish residents looking for a relatively stable lifestyle. Pivach, who was crowned the king of the 2002 Orange Festival, said that his grandparents on his father’s side were among a number of immigrant families from what’s now Croatia who bought farmland in Triumph to transition from oyster fishing to citrus growing. “They developed the grove,” he said. “They developed the oranges.” That allowed them to spend time with their young families more easily than would have been possible commuting back and forth to remote fishing camps. “At that time, if you were an oyster fisherman, you spent 90 percent of your time out at the marsh, in the camp,” he said. “You can’t educate a child in the Louisiana marsh.”

Pivach’s grandparents started making orange wine when they had excess oranges or fruit that was too blemished to sell. By 1938, his grandfather was operating a licensed winery that went on to sell wine carried by stores throughout the New Orleans area and beyond. “They, along with the [nearby Lulich family], revived and/or developed the orange wine industry and commercialized it until 1962,” Pivach said. That’s when the parish’s orange crop was decimated by a winter freeze. “My dad and mom saw it coming—they picked as many oranges as they could and then immediately started making orange wine,” Pivach said.

Pivach’s grandparents started making orange wine when they had excess oranges or fruit that was too blemished to sell. By 1938, his grandfather was operating a licensed winery that went on to sell wine carried by stores throughout the New Orleans area and beyond. “They, along with the [nearby Lulich family], revived and/or developed the orange wine industry and commercialized it until 1962,” Pivach said. That’s when the parish’s orange crop was decimated by a winter freeze. “My dad and mom saw it coming—they picked as many oranges as they could and then immediately started making orange wine,” Pivach said.

Even the Orange Festival was cancelled in 1962 due to the destruction caused by the frigid temperatures. The Pivach winery was destroyed that year by an unrelated explosion. Pivach’s family and other citrus farmers planted new trees, but in 1965, Hurricane Betsy struck southern Louisiana, destroying the newly replanted groves through saltwater intrusion. Hurricane Camille in 1969 would do further damage to the parish’s orange crop, and the Pivach family would never again commercially produce orange wine. The Lulich winery similarly shuttered in 1965 after Betsy, according to newspaper reports. The entire local citrus industry was badly hit: essentially no citrus production was reported in the state after 1965 until the 1970s, according to a 2017 study by researchers at Auburn University.

By 1980, United Press International reported on the closing of the parish’s last orange winery: Sig’s Orange Wine, created by Sig Udstad in 1972 to fill the gap created by the closure of the Pivach and Lulich wineries. Udstad grew some oranges behind his celebrated Sig’s Antique Restaurant in Port Sulphur and sourced some from other farmers, said Fertel. Udstad’s winery was also a bit of a family affair, he said, with Ruth Fertel of steakhouse fame helping to produce the beverage and sell it at the Orange Festival.

“My mother used to say that during the crush—what winegrowers would call the crush, when they would squeeze all the oranges—her hands were never so soft because of that oil, that peel oil that would get on her hands and soften her skin,” Fertel said.

Sig’s also employed local high school students to wash and juice oranges, according to the United Press International report, and ultimately labor and other costs made the winery unsustainable, especially with Udstad also operating his restaurant, which Fertel said was a destination for fishermen returning from a day out on the water.

“It really was just a hobby,” Udstad told a reporter at the time. “But it got bigger than that, and I couldn’t do it all anymore.”

Since then, the Plaquemines Parish citrus industry has continued to be affected by hurricanes, coastal erosion tied to global warming, and occasional low temperatures, including a devastating freeze in the late 1980s that caused nearly 100 percent tree death, according to the Auburn study, which reports: “There are very few, if any, commercial citrus trees along the Gulf Coast that were planted before 1989.”

And while citrus production has to some extent rebounded, albeit with a declining number of growers over the years, orange wine has largely disappeared from restaurant menus and store shelves. The New Orleans City Council even repealed ordinances regulating its production in 2019 as it removed archaic provisions from its liquor laws. Demand for sweeter wines in general has declined, Fertel suggested. “This might be a snob’s response, but I collect wine, and the American palate has improved,” he said.

Nowadays, even some local liquor vendors and wine aficionados are more acquainted with the amber-hued grape wine also known as orange wine than with the beverage produced from actual citrus. “Orange wine is a super niche wine,” Fertel said. “Most people when they hear orange wine, they say, what? You can make wine out of oranges?”

The sole remaining commercial orange wine producer in Louisiana is Amato’s Winery in Independence, which also makes other fruit wines, including strawberry, blueberry, peach, and cranberry varieties. The wines can be found for sale in local grocery and liquor stores. Henry Amato, who started the winery in 1993, said it took about two years of trial and error to develop a quality orange wine, which is produced using oranges from Plaquemines Parish farmers.

“The orange wine is probably the hardest wine to make because you’ve got to keep it real cool, because if you don’t, it’ll oxidize on you,” he said. “It gets rancid.”

While Amato’s Winery may be the last source of Louisiana orange wine for purchase, others are still continuing to make orange wine in small batches at home, perhaps not too differently from how people did during Prohibition. Pivach said he and his brother Mark have been gathering relatives together once a year since 2008 to make a barrel or two that they proudly share with family and friends. “My mom takes the first sips,” he said. “She’s the official taster—makes sure it meets the Pivach quality.”

Naturally, the family uses locally grown oranges to make the wine, he said. “That would be a sin to use anything but Plaquemines Parish oranges,” said the onetime festival king. “We grow the finest oranges anywhere, bar none.”

Steven Melendez is an independent journalist based in New Orleans.