Looking for “Petit Jean”

Legacies of French-Colonial Louisiana in Arkansas

Published: February 28, 2025

Last Updated: May 30, 2025

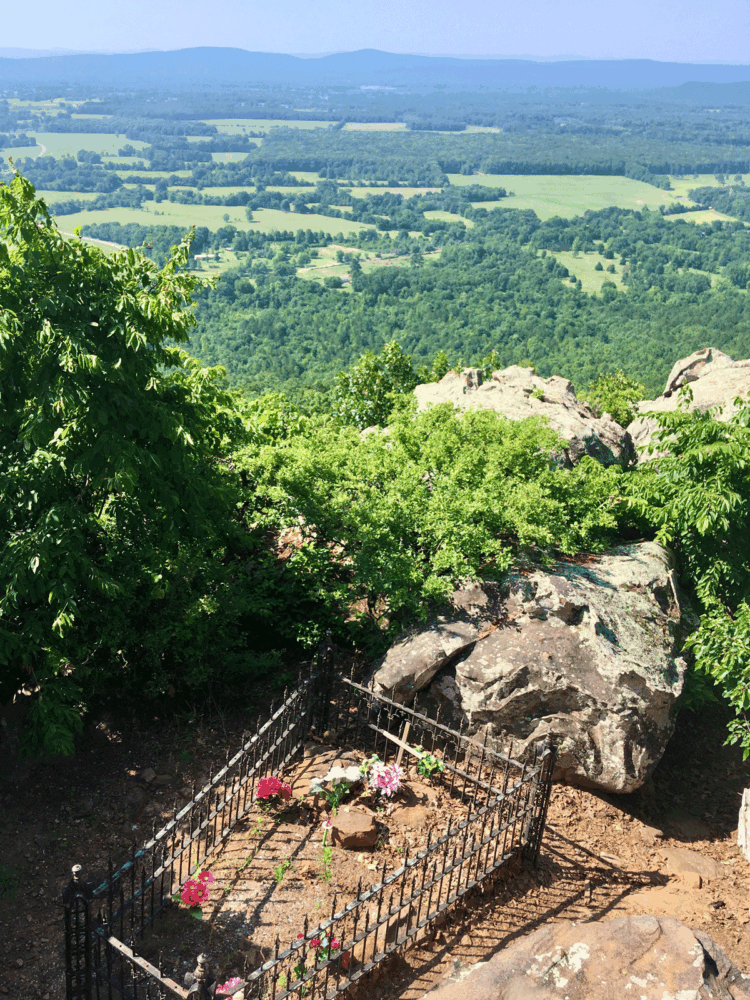

Photo by Nathan E. Marvin

The Petit Jean Gravesite at Petit Jean State Park in Conway County, Arkansas.

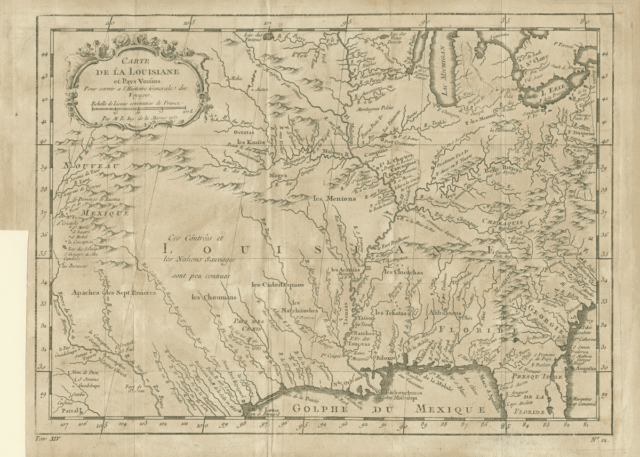

In 1686, the French established a foothold along the Arkansas River in O-ga-xpa Ma-zhoⁿ, the homeland of their Quapaw allies. In 1731, having failed repeatedly to develop a lasting settlement in the region, the government in French Louisiane sent a dozen soldiers to rebuild and expand the fortified site they called Arkansas Post. The small post would become the most significant settlement in French Louisiane between Natchitoches and the Illinois Country, a linchpin connecting Upper and Lower Louisiane. A heterogeneous community developed in and around the Post, composed of free persons from Europe of various backgrounds and statuses, as well as African and Indigenous bondspeople.

Today, the site that evokes this French colonial past for most Arkansans is Petit Jean Mountain, more than one hundred miles upriver from the Post. Rising above picturesque farms along a bend in the Arkansas River, Petit Jean Mountain is the oldest of Arkansas’s state parks and one of its most popular, attracting eight hundred thousand visitors annually. After navigating the hairpin turns that lead to the mountain’s summit, visitors are greeted by the Petit Jean Grave Site, a fenced-in mound of earth adorned with a simple wooden cross, perched on a precipice overlooking the valley below.

A series of panels here and in the nearby visitor center explains “The Legend of Petit Jean”: At some point “in the eighteenth century,” a young French woman disguised herself as a cabin boy to join her fiancé aboard a ship destined to explore “uncharted regions of the new world.” Beloved by her shipmates, who nicknamed her Petit Jean (“Little John”), she concealed her true identity until she fell gravely ill while exploring the Arkansas River. Petit Jean died shortly after revealing her secret to her lover, who named the mountain in her memory.

What are the origins of this legend? When did it emerge? While it contains no verifiable historical details—even the state park signage describes it as “folklore”—it includes tropes that would have been familiar to nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century US audiences. The theme of lovers crossing the Atlantic to seek a new life, only to see their dreams dashed in Louisiana, evokes Abbé Prévost’s Manon Lescaut, while the gender-bending elements are reminiscent of Joan of Arc. Indeed, in a 1999 undergraduate thesis, DeAnn McGrew of the University of Central Arkansas traces what may be the earliest version of this story in print to an 1878 newspaper article—one of the first issues of The Dardanelle Western Immigrant, aimed at attracting settlers to the region.

Though the female Petit Jean legend is not the only version to have appeared in print—other origin stories include male figures, such as an aristocratic “Jean” escaping the ravages of the French Revolution to settle on the mountain—the twentieth century saw the story of a female Petit Jean further popularized by local writers. Lucille Clerget Rankin published books of poems that broadly cited items discovered in the local library, as well as an “oft-told Indian legend,” as her sources. In 1955, Marguerite Turner expanded the tale in her book Petit Jean: A Girl, a Mountain, a Community, apparently devising the French names for the characters that are used in the state park panels. That same year, Dr. Thomas William Hardison, a key figure in the establishment of Arkansas’s first state park, published a promotional brochure featuring a variation of the female Petit Jean tale.

As for the gravesite’s origin, a 1997 blog post signed by “RTJ” reported that the Stout family—local entrepreneurs—recruited community members around 1912 to construct a false gravesite, hoping to attract honeymooners to a hotel they built on the mountain with the romantic tale of the female Petit Jean. Based on interviews with a state park interpreter, the post suggested this fabrication was central to the legend’s modern form.

Despite skepticism about the tale’s authenticity, the Petit Jean name remains one to conjure with in Arkansas. The “Petit Jean” brand graces all manner of products, from artisanal cheeses to craft beer. Odes to the mountain and its French maiden namesake continue to appear, including a composition for the Arkansas Symphony Orchestra by Christopher Theofanidis (2014), and a children’s book by William B. Jones and Gary Zaboly (2016) that uses the story to convey the broader history of the French presence in the region.

However, a close examination of the archival record of colonial Louisiana suggests a real historical figure as the namesake of the Petit Jean River and Mountain. His story is far removed from that of the tragic French maiden in nearly every aspect but the spot on which both are said to have died. In a footnote to his seminal 1991 study of Arkansas Post, historian Morris Arnold points to a 1734 report by the Louisiana Governor Bienville to the Ministry of the Navy in Versailles regarding an Osage attack on a French hunting party along the Arkansas River upriver from the Post, naming a “Petit Jean” as one of the victims. The present article picks up where Arnold left off, mining the historical record for clues about the identity of the man and contextualizing what we can establish about the circumstances of his death and its broader implications for the history of French Louisiane.

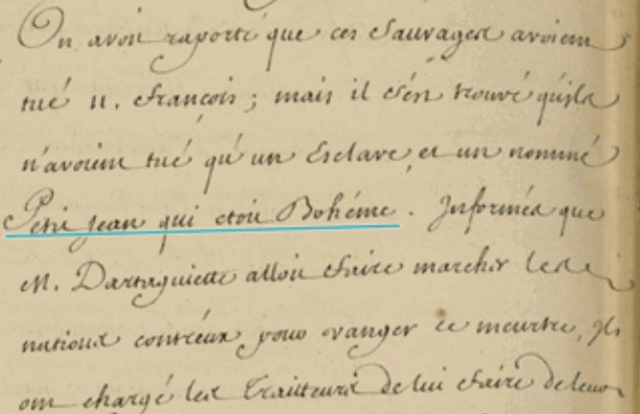

Letter of Governor Bienville to the Minister of the Navy, the comte de Maurepas, New Orleans, July 27, 1734. Archives Nationales d’Outre-Mer, Aix-en-Provence

The Bienville report is one of two documents that relay the incident, written at the highest levels of French imperial bureaucracy and housed in the Overseas Division of the French National Archives. These two reports appear to correspond to a story reported in an 1869 issue of the Arkansas Gazette, the state’s oldest paper. The piece recounts the origin of the name of nearby Petit Jean Mountain, said to have been gleaned from local “tradition.” It describes “Petit Jean” as a cook who served a group of soldiers—not hunters in this version, although in French colonial Louisiana there would have been much overlap there. According to the tale, during a nighttime raid, a party of Osages attacked the camp. The body of Petit Jean was discovered on the banks of the river, at the foot of the mountain. The soldiers buried him by the mountain that now bears his name.

The French reports help establish a basic timeline. In 1732, the French commandant of Arkansas Post, Pierre-Louis Petit de Coulange, had authorized a risky upriver expedition of voyageurs deep into the heart of Osage hunting grounds. When no word came from the French hunting party, the commandant reported to New Orleans that all eleven members were missing and feared dead. In April 1734, the newly reappointed governor of Louisiane, Bienville, put pen to paper to report the latest developments to his superior, the Minister of the Marine: “The news that I had the honor of sending to Your Greatness, regarding the letters I had received about the murder of eleven canoemen (voyageurs), of which the Ozages [sic] were accused, has only been partially confirmed.”

Upon first news of the Osage attack, colonial authorities in New Orleans had resolved to mobilize a force of French soldiers and Native allies to exact revenge. Officials were still reeling from the attack of their erstwhile allies, the Natchez, in Fort Rosalie, which had led to a destructive war with that nation. However, their plans shifted when the true number and identities of the victims were revealed. The Osages had attacked the party’s riverside camp while most were away. Bienville sent an update to Versailles in July 1734: “It had been reported that these Indians had killed 11 Frenchmen, but it turned out that they had killed only a slave and a so-called Petit Jean, who was a Bohemian.”

A temporary stoppage was ordered in trade with the Osages. As soon as they heard the accusations from Arkansas Post, the Osage moved quickly to present their side of the story. They asked French traders along the Missouri—the heart of their territory—to convey their apologies to the commandant of Arkansas Post. They even sent a delegation, offering compensation equal to the value of the fallen slave. The Osage admitted responsibility for the two deaths but, regarding their second victim, “Petit Jean,” they repeatedly insisted that they had mistaken him for an Indian (sauvage), emphasizing that they had no intention of harming “any French man.”

The Osages’ explanations were deemed sincere, and their reparations sufficient. Bienville concluded, “I do not believe it appropriate, given the state of our affairs, to pursue this matter further. We do not need to seek out new wars.” In France, the Minister of the Marine signaled his agreement with a simple margin note: “Approved.”

The earliest printed accounts of “Petit Jean”…distort his identity, erase any mention of the enslaved man who died alongside him, and deny the Osage any legitimate agency.

The identities and social positions of the two victims undoubtedly influenced this decision. While the price of the unnamed enslaved man was compensated, Petit Jean was apparently not considered valuable enough to justify costly retaliation for his death. Governor Bienville’s descriptions of Petit Jean, who is never given a family name in the documents, provide some clues. He refers to Petit Jean as an engagé—an indentured servant responsible for navigation, maintenance, and camp setup for licensed groups of voyageurs. More importantly, the governor twice emphasized that Petit Jean was “a Bohemian.”

What did that word “Bohemian” signify, and why was it meaningful enough for the governor to include it twice in justifying his decision not to punish the Osage beyond a temporary suspension of trade? In early modern France and its empire, the term “Bohème” (“Bohemian”) was used in official documents to refer to Roma. It may be the case that French officials, like the Osages in their telling of the 1732 incident, viewed Romani members of the Louisiane community as neither fully white nor fully French.

Linguistic and genetic evidence trace the origins of the Romani diaspora to South Asia, out of which they began migrating approximately 1,500 years ago. The Roma reached Western and Central Europe by the 1300s, after passing through Persia and the Balkans. They faced widespread persecution, including systematic enslavement in some regions. During the Renaissance, many Roma arrived in France, where they were called “Bohèmes” for the letters of protection they carried from Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia. The Roma were not universally unwelcome in France. In the Lorraine region especially, nobles offered them protection in exchange for entertainment. The French aristocracy romanticized the Roma, associating their horsemanship, colorful clothing, and perceived freedom of movement with the chivalric pageantry of the Crusader era. But in 1682, Louis XIV ordered the expulsion of Romani men and women from France and even threatened to strip nobles who harbored them of their titles. Several historical factors contributed to these persecutions: Louis XIV was attempting to shore up his power against the nobility, and France was in the grip of a major economic crisis. The “Bohèmes” emerged as convenient scapegoats for the ills of the king.

Uncolored engraving from 1757 showing French Louisiana, which formerly included parts of contemporary Arkansas, and adjacent colonial territories of England and Spain. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

For more insight into the possible identity and trajectory of the man called “Petit Jean” in the 1730s documents, we turn to the meticulous detective work of historians Ann Ostendorf and Elizabeth Shown Mills. A portion of Romani prisoners was deported to Louisiana to serve in the army or contribute to the settlement of the struggling colony. “Petit Jean” may have arrived in North America aboard the Tilleul, which departed Dunkirk in 1720 carrying dozens of “Bohémiens” and landed in Biloxi. Some Roma settled in New Orleans, from which sporadic military expeditions—including companies composed entirely of “Bohèmes”—were mobilized and sent up the Mississippi to protect the Arkansas Post and the Illinois Country settlements.

There are two entries for Jean, “Bohémien,” on the passenger list of Le Tilleul—Jean Gaspart and Jean Christophe. Both Jean Gaspart and Jean Christophe (if they were indeed separate individuals) are associated in the historical record with Marie Agnès Simon, a Romani woman who also arrived aboard Le Tilleul. In 1732, a “Marie, bohémienne,” was recorded as living on the Saucier property at the corner of Royal and St. Peter Streets in New Orleans’s French Quarter. She was not living with a husband at that time, although she is known to have been the spouse of Jean Gaspart at some point, and to have remarried after his death. Could Jean Gaspart have been the same “Petit Jean” who died on the banks of the Arkansas River?

Interestingly, while the Roma occupied an ambiguous racial position in eighteenth-century Louisiana, this “racial liminality”—to borrow Ann Ostendorf’s expression—allowed them to navigate social and legal systems in ways not always explicitly permitted by law. For instance, in 1725, Marie Jacqueline Gaspart, daughter of the above-mentioned Marie Agnès Simon, married Jean-Baptiste Raphaël, a free Black man from Martinique. The Code Noir of 1724 prohibited marriage between “whites” and “Blacks.” But though Roma were often assimilated into the white population, they were also occasionally categorized separately or included among the gens libres de couleur. The parish priest sought special approval from the governor to perform the wedding ceremony, which was granted.

Regardless of whether “Petit Jean, Bohémien,” is the authentic namesake of Arkansas’s oldest state park, the story of the two men who died in 1734 along the Arkansas River—Petit Jean and his unnamed enslaved companion—reveals the convergence of three processes of historical dispossession in the heart of North America: the persecution of Roma in Europe, chattel slavery, and the rise of settler colonialism. The earliest printed accounts of “Petit Jean” for English-speaking audiences distort his identity, erase any mention of the enslaved man who died alongside him, and deny the Osage any legitimate agency. By the middle of the twentieth century, regional promoters embraced the fabricated—and arguably more palatable—tale of a female Petit Jean, a version that endures to this day. The historical Petit Jean challenges these whitewashed portrayals of the French colonial period in Arkansas and exposes the diversity and violence of la Louisiane’s frontier.

Nathan E. Marvin is an Assistant Professor of History at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. His work examines colonialism, slavery, and resistance in French imperial spaces across the world. His book manuscript, Bourbon Island Creoles: Race and Revolution in France’s Indian Ocean Colonies, traces the effects of the French and Haitian Revolutions on the politics of race in France’s Indian Ocean colonies of Réunion and Mauritius.

Bibliography

Arnold, Morris S. Colonial Arkansas, 1686-1804: A Social and Cultural History. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1991.

Bandy, Everett. “O-Ga-Xpa Ma-Zhon: Quapaw Country.” Informational Paper. Quapaw Nation (Oklahoma), 2020.

Daily Arkansas Gazette. Little Rock, Arkansas. November 3, 1869, p. 3. Accessed April 16, 2024.

Filhol, Emmanuel. “Bohémiens condamnés aux galères à l’époque du Roi-Soleil (1677 à 1715).” Criminocorpus. Revue d’Histoire de la justice, des crimes et des peines, June 2, 2020.

Hancock, Ian F. We Are the Romani People. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2002.

Hardison, T. W. “A Place Called Petit Jean: The Mountain and Man’s Mark.” 1955. UCA Archives & Special Collections, PAM-1777

McGrew, DeAnn. “Origins of the Legend of Petit Jean.” Undergraduate thesis, University of Central Arkansas, December 10, 1999. UCA Archives & Special Collections, SMC 1202.

Mills, Elizabeth Shown. “Assimilation? Or Marginalization and Discrimination?: Romani Settlers of the Colonial Gulf (Christophe Clan).” Genealogical Resource, June 6, 2015. Accessed December 20, 2024.

Ostendorf, Ann. “Louisiana Bohemians: Community, Race, and Empire.” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 19, no. 4 (2021): 659–98.

Rankin, Lucille Clerget. “The Legend of Petit Jean Mountain.” 1946. UCA Archives & Special Collections, PAM-1776.

RTJ. “The Many Legends of Petit Jean.” Arkansas Road Stories, May 8, 1997.

Nuttall, Thomas. Travels into the Arkansas Territory, 1819. Vol. 13 of Early Western Travels, 1748–1846, edited by Reuben Gold Thwaites. Cleveland, OH: The Arthur H. Clark Company, 1905.