Los Adaes

An old capital of Texas and center for Native trade

Published: August 29, 2022

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

British Library / Alamy Stock Photo

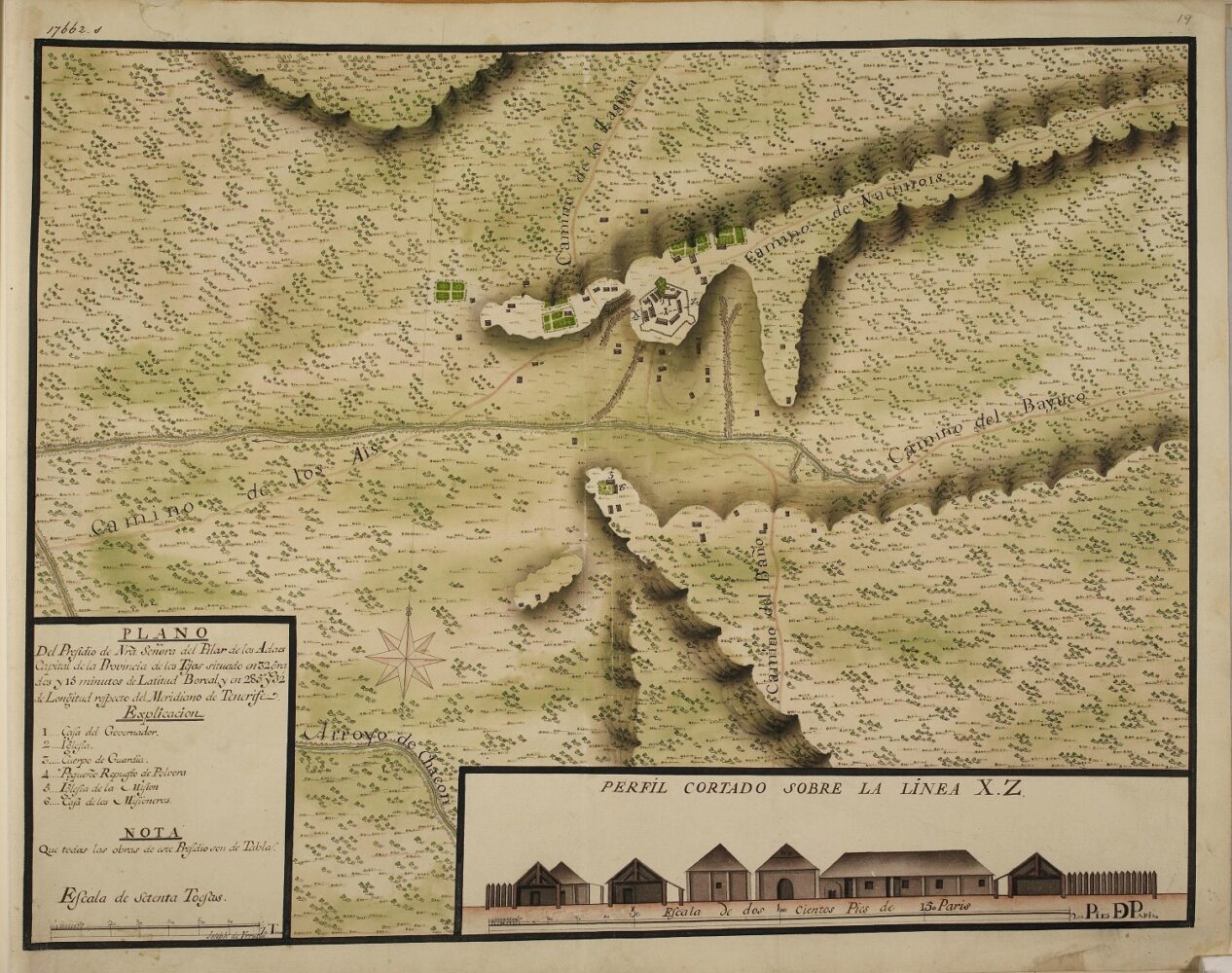

“Plano del Presidio de Nuestra Señora del Pilar de los Adaes, capital de la provincia de los Tejas” drawn by Joseph de Urrutia, ca. 1768.

San Miguel de Cuellar was founded by Franciscan priests from Querétaro in northern Mexico and led by the Blessed Fray Margil de Jesús, currently a candidate for sainthood in the Roman Catholic Church. Intended for the small Caddo-related Adais tribe, the mission implanted Roman Catholicism here on the frontier between Spanish colonial Texas and French colonial Louisiana. The presidio was a military garrison established to prevent incursions into Spanish territory. It served as a border post at the northeastern edge of Texas. The French establishment, Fort St. Jean Baptiste des Natchitoches, was located just fifteen miles to the east and had control over the only corridor to the west, El Camino Real de los Tejas, which connected Los Adaes to the seat of royal power in Mexico City.

When Northwestern State University archaeologist Dr. Pete Gregory first came to Los Adaes in the 1960s, the site was owned by the Colonial Ladies organization, who then transferred it to Natchitoches Parish. The Los Adaes Foundation provided upkeep, and Gregory helped the foundation get the site on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974. Four years later the parish donated the site to the state, which then purchased additional surrounding land. Los Adaes was recognized as a National Historic Landmark in 1986.Gregory has undertaken the most significant excavations at the site to date, uncovering roughly 5 percent of the site’s features. His excavations, which took place from the mid-1960s to the mid-’80s, had three aims: verify that this was indeed the site of Los Adaes; locate the presidio wall and associated features; and excavate in the area where a new archaeology lab and visitor’s center would be built. Essential to the process were two maps—one an architect’s plan, the other a 1768 map of the presidio, mission, and associated structures.

When Dr. George Avery, now an archaeologist at Stephen F. Austin State University, came to Los Adaes in the mid-1990s as a station archaeologist, he followed Gregory’s strategy of digging only when necessary. There had been a severe storm in 1994, and over one hundred trees had been broken or dislodged. Avery water-screened excavated material using a 1/16-inch mesh window screen to recover the smallest artifacts, such as tiny trade beads called “seed” beads. Comparing seed bead color patterns found at both the presidio and mission, he determined that the pattern of seed beads recovered from Mission San Miguel de Cuellar was remarkably similar to the pattern of beads recovered from the “sister” mission, Dolores, built the same year in San Augustine, Texas, about sixty miles away.

In the mid-2000s another important archaeological survey was completed on site, when Los Adaes was chosen as a location for a geophysical workshop by Dr. Michael Hargrave. Participants in the field school operated various geophysical survey machines, including ground penetrating radar, magnetometers, resistance meters, and the EM-38, which measures both electro-magnetic susceptibility and conductivity. The EM-38 helped locate the presidio wall as well as the outlines of the interior structures, with their hearths. (Gregory’s previous archaeological work had found the walls of the presidio and several features, but the interior structures were a new find.) Researchers also found what they suspected were two rows of barracks buildings on the eastern side of the presidio. Hargrave later brought in staff from Stephen F. Austin State University to do ground truthing of various areas to validate the results of the geophysical surveys, and all areas indeed showed archaeological features where the geophysical surveys had shown anomalies.

Workers explore the areas near and under fallen trees after Hurricane Laura. Photo by Chip McGimsey.

The most recent archaeological field work was coordinated in 2020 by Dr. Chip McGimsey, State Archaeologist of Louisiana, and Avery. Storm activity from Hurricane Laura hit Los Adaes and knocked down several trees, which provided a research opportunity. McGimsey recruited a cadre of volunteers, from schools in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Lafayette, Natchitoches, and Shreveport, as well as the Louisiana Archaeological Society chapters in Leesville and Shreveport, to remove the disturbed deposits around the trees’ root masses and then water screen the deposits. Roughly forty seed beads have been recovered, along with a large number of Native American and European pottery sherds that date to the time when the mission was active. Some glass and metal-iron artifacts were also recovered—mostly hand-wrought nails.

Trade at Los Adaes between the Spanish and the French and American Indians was mostly restricted—while the Spanish were specifically forbidden to trade guns or alcohol, they could trade for food, which they undoubtedly did. French trade goods are also found at Los Adaes, and French traders are listed in the archival record as occupants of the settlement. An abundance of metal artifacts has been found at Los Adaes, some French, but mostly Spanish. (Jay Blaine, an avocational archaeologist from Texas, supported site research by identifying all the metal artifacts and conserving some of the more significant ones.) The Spanish, generally, had horses to trade. The French generally had cloth, and the local Native Americans had food that supplemented the provisioning system for Spanish soldiers, which involved a yearly trip to Mexico.Archaeologists generally focus on pottery to sort out where goods found on site came from. As you might expect at a Spanish fort, Spanish pottery is present at Los Adaes, but French and British pottery is present in roughly equal amounts. There is also a huge quantity of American Indian pottery—roughly 90 percent of the total amount found to date. Many of these artifacts can be viewed at the Williamson Museum at Northwestern State University.

Los Adaes today. Photo by Chris Turner-Neal.

The Spanish Lake Community, located a few miles north of Los Adaes, is home to the Adais–Caddo Nation and Spanish descendant families, and serves as evidence of Los Adaes’s long-standing cultural impact. Spanish Lake residents often have Spanish surnames, many of which were connected to Los Adaes. As late as the mid-twentieth century, community members were Catholic, spoke Spanish, and traditionally prepared tamales. As the twentieth century moved on, the Spanish language fell out of use in the area, but the Catholic Church and tradition of tamale-making remain to this day.

The Choctaw–Apache Tribe of Ebarb lives northwest of Los Adaes in Sabine Parish. Its members are directly connected to the fort and mission’s Spanish and Indigenous populations. Their Choctaw ancestors were relocated by the first local American Indian agent, Dr. John Sibley, west of Los Adaes, and they joined with the Indo-Hispanic families from Presidio Los Adaes. Like the Adais–Caddos they are predominantly Roman Catholic, and until recently both communities spoke a very conservative dialect of Spanish—one of the least changed on North America’s former Spanish colonial frontier. Foodways and language are direct connections between Los Adaes’s past and present.

While the State of Louisiana still maintains ownership of Los Adaes, Cane River Creole National Heritage Area assumed management of the property in 2017. Recently Logan Schlatre, a ranger for the Cane River National Heritage Area, found part of a rare type of olive jar. Discoveries of important artifacts are still being made at this old Texas capital.The story of Los Adaes has been followed by historians and archaeologists working to achieve greater understanding of the past by combining information from paper records with what we can learn from objects and structures excavated from beneath the earth. After all this time, the descendants of the multi-ethnic populations who lived and died at Los Adaes can take their children to the place of their ancestors, where people still come to play and also to pray. Los Adaes is no longer one of “los olvidados”—forgotten ones.

George Avery holds a PhD in anthropology with an emphasis in archaeology from the University of Florida at Gainesville. He spent ten years starting in 1995 as the Los Adaes station archaeologist and is currently a staff archaeologist at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas.

Hiram F. “Pete” Gregory has spent his career as an archaeologist/ethnologist at Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana. He was awarded the LEH Lifetime Achievement Award in 2019.