Geographer's Space

Louisiana Radio Stations and the (Inconvenient) Local Music Lacuna

Louisiana is the birthplace of several musical genres, but when locals turn their radios on, something very different is likely to come out

Published: December 1, 2015

Last Updated: October 30, 2018

But what music are Louisianians consuming? That is, what genres and artists are actually listened to by the 4.4 million of us, and not just the critics and connoisseurs who do most of the music discoursing? Is our aggregate consumption as heavily Cajun and zydeco, or jazz–blues-funk, as the production side of the scene might suggest?

Music consumption may be estimated in a variety of ways, including online activity, purchases, playlists and live-performance attendance. In this column I use radio station formats as a gauge of listenership.

First, a preemptive rebuttal: As in any quantification of a complex phenomenon, airplay is an imperfect measure of musical tastes. For one, not everyone listens to the radio, and certainly not all day. Many stations play a wider variety than their branded format (classic rock, oldies, adult contemporary) might suggest, and those with seemingly nationwide formats (urban, which usually implies hip-hop and rap) may in fact air locally produced material such as bounce, brass band, or second-line music. Others, particularly public and college stations, play eclectic musical segments in pointed defiance of single-genre programming, while the conglomerates behind many commercial stations generally drive musical tastes as much as they reflect them. So while I acknowledge that radio station formats shine only so much light on overall musical consumption, the patterns they illuminate are nonetheless informative and revealing because ultimately it is we listeners who control the dial. Stations constantly reposition themselves so that we select them and their musical offerings. Since the advent of the median, radio stations have both created and reflected our collective tastes, and I would posit they generally do the same among Louisianans—thus they’re a reasonable dataset for this analysis.

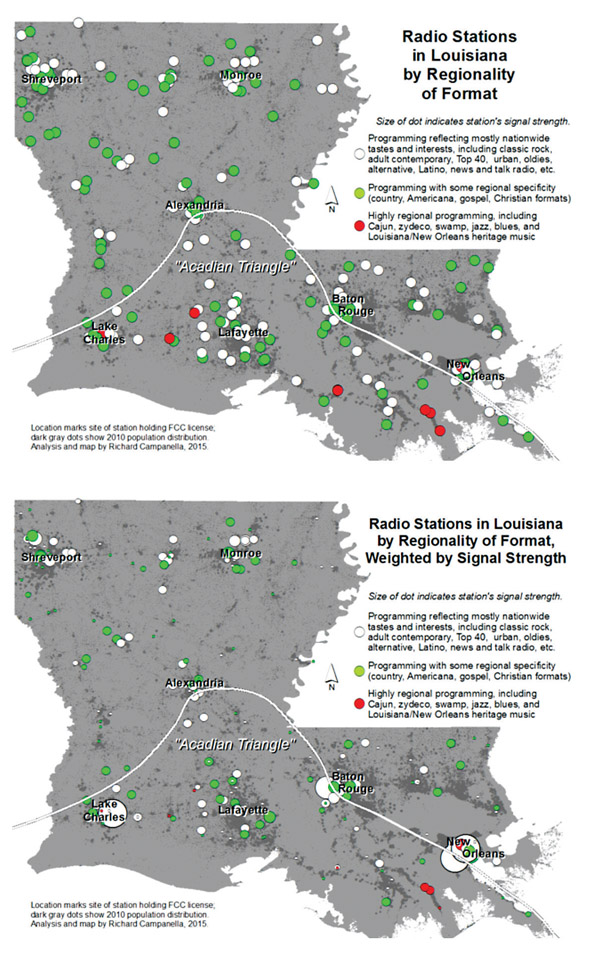

To understand patterns of musical consumption on the airwaves, I gathered Federal Communications Commission licensing records, tagged each station by their broadcast locations and signal strengths, determined their primary format courtesy of their branding and airplay, and binned the varying descriptions into 30 main format categories. Then I mapped out the results.

Maps by Richard Campanella.

What we see might surprise those Americans who, inculcated by relentless media representations, imagine a Cajun soundtrack accompanying every Louisiana landscape. But it would not surprise anyone who has ever driven across the state with their finger on the scan button. Louisianians are much more likely to listen to—or at least hear—musical genres with global appeal than those rooted locally.

Consider, for example, the map titled Radio Stations in Louisiana by Regionality of Format (see above). The numerous white and green dots representing stations playing global, national or regional (that is, Southern but not particularly Louisianian) music are evenly distributed throughout the state, and occur both north and south of the “Boudin Curtain” separating the Anglo-dominant Protestant north from the Acadian Triangle and the mostly Catholic south.

The pattern (or lack thereof) grows stronger when we weight the stations by the power of their broadcast signals (see map above, Radio Stations in Louisiana by Regionality of Format, Weighted by Signal Strength).

According to these maps, Louisianians are consuming more or less the same music as Americans elsewhere.

Spots of localism do occur, and for good reasons. If we might expect the state’s only jazz, blues, and Louisiana/New Orleans music station to be in the putative “Birthplace of Jazz,” we would be correct: it’s New Orleans’ listener-supported WWOZ. Likewise, if we would predict Cajun, zydeco, and swamp-pop stations to predominate in the Cajun region south of the Boudin Curtain, we’d be right again: all seven are within the Acadian Triangle.

But for every confirmation of an expected local pattern (red dots), we see much more evidence that mainstream genres prevail broadly. Poring over the distribution of Christian programming, adult contemporary, classic rock, Latino and urban, which are numerically overwhelming and scattered evenly across the state, one suspects there is greater variation of musical preference within Louisiana communities than among them. The only exceptions are precisely those genres for which the state is famous—Cajun, zydeco and jazz—which really do form a distinct, albeit highly confined, geography.

Phrased another way, relatively few Louisianians are consuming the famous local genres that get all the attention on the production side—and the little local music that does get airplay tends to occur in very limited geographies. Louisianians who consume global material, meanwhile, do so in larger numbers, in broader spaces, and with little fanfare from Louisiana music writers.

Other non-radio measures corroborate that we’re not listening to the music we’re “supposed to.” The data-mining platform Echo Nest (the.echonest.com), which analyzes musical trends through billions of online data points, determined that the top artist listened to in Louisiana was not BeauSoleil, Dr. John, the Neville Brothers, or Rosie Ledet—but the Canadian-born rapper Drake. Indeed, most of Louisianians’ favorite performers according to Echo Nest’s metrics were out-of-state artists known mostly for hip-hop and rap. Only when its analysis aimed to identify the “most distinctive artist by state”—that is, “the artist…listened to proportionally more frequently in [Louisiana] than they are in all of the United States”—did a local talent top the list: Baton Rouge-born rapper Kevin Gates.

Returning to our radio data, the top three most common station formats in Louisiana, regardless of signal strength, are Christian (54 stations, many including talk programming), country (both modern and classic, 45 stations), and adult contemporary (including urban adult contemporary, 31 stations). We have to go fairly far down the list before getting to gospel (13), Cajun, zydeco and swamp pop (7), and jazz, blues, funk (1).

This inconvenient lacuna of localism has not been lost on local music aficionados, and at least one prominent voice seemed perplexed by it. “Why aren’t local radio stations playing more local music?” asked Jan Ramsey, longtime editor of New Orleans’ Offbeat Magazine in an October 2014 editorial. Relatedly, she puzzled over the proclivity of Louisianians planning Carnival krewe balls or similar festivals—folks who ought to personify what we mean when we say “locals”—to hire ordinary pop bands covering national standards. “I just think it’s a real shame,” Ramsey sighed, “that with the rich musical tradition that we have[,] most of the population doesn’t respond all that well to local musicians.” The paradox begs the question of what exactly “local music” means, to which side of the production/consumption dualism it applies, and to what extent Louisiana society is musically distinctive.

Being a geographer rather than a musicologist or music critic, I will refrain from making any sweeping conclusions from this cursory analysis. But I would point out that, to the degree that a society’s musicality implies consumption as well as production, an empirical look at radio station formats reveals a wide gap between (1) the perception of localism in all things musical in Louisiana, and (2) the reality that national mainstream music wins over many, many Louisiana ears.

Indeed, if this issue of Louisiana Cultural Vistas were devoted to the music we’re listening to, you might be reading about Drake right now.

—–

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Bienville’s Dilemma, Lincoln in New Orleans, Bourbon Street: A History, and most recently, The Photojournalism of Del Hall (LSU Press, 2015). He may be reached through richcampanella.com or [email protected]; and followed on Twitter at @nolacampanella.