Louisiana’s Old Live Oaks

Story-laden trees anchor the Louisiana landscape

Published: June 1, 2024

Last Updated: September 4, 2024

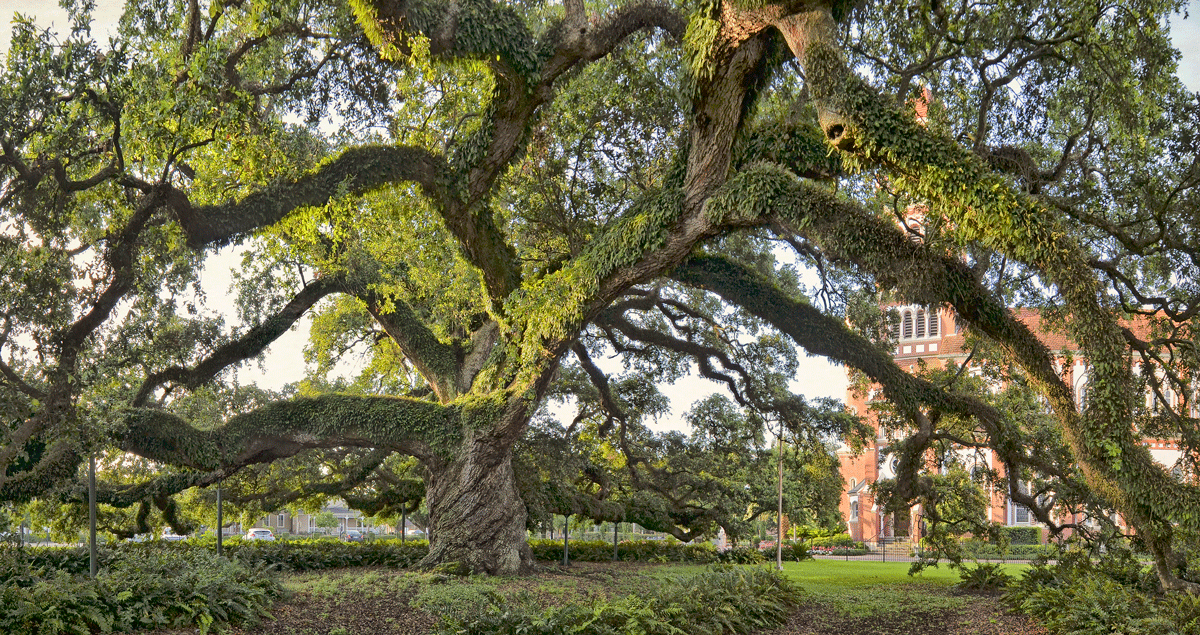

Photo by William Guion.

The Seven Sisters Oak in Mandeville.

There’s a strange mystique that surrounds Louisiana’s live oaks. Locals and visitors acknowledge it, and artists, writers, and storytellers try to describe it. This is especially true of the oldest oaks, those dripping in Spanish moss. The southern live oak tree (Quercus virginiana) has grown into an icon, signifying strength, endurance, and longevity. The oldest oaks are living memorials, predating European colonization. Under the massive arch of ancient oak limbs Choctaw elders gathered in council, Spanish explorers camped, sermons were preached, and treaties were signed. Lovers met in secret, couples shared vows, quarrels were settled, blood was spilled. In Louisiana, live oaks are history, heritage, and heirlooms rolled into one.

These remarkable trees are also generous neighbors, contributing much to the history, culture, and quality of life in the bayou state. In addition to their support in pollution fighting, erosion and storm water control, and wildlife shelter, live oaks add an unmistakable character and beauty to towns, city streets, yards, parks, and open fields. People gather under them to socialize, celebrate, share good times, and make memories. On old maps, trees mark where property lines met, and where back roads crossed.

The most familiar oaks are often given a name. A named oak becomes our oak instead of just that tree. This difference presents an oak with a better chance of survival when someone with a chainsaw believes it’s in the way of progress and profit. Louisiana has hundreds of such named and honored oaks. The Bowie Oak on Bayou Lafourche grows on the site where Jim Bowie (of Alamo fame) lived with his mother and two brothers. The McDonogh Oak in New Orleans City Park is named after shipping magnate and philanthropist John McDonogh, who bequeathed the land that became City Park to the City of New Orleans.

Many named oaks are enrolled in the Live Oak Society, founded with the goal to honor and protect the state’s oldest live oak trees. The society is the brainchild of Dr. Edwin Lewis Stephens, the first president of the Southwestern Louisiana Industrial Institute (now the University of Louisiana at Lafayette). The organization began in 1934 with forty-three oaks and has grown to include more than ten thousand member trees across the South. The society’s members are all trees, except for one human chairperson (a position currently held by Ms. Coleen Perilloux Landry).

But for all their popularity and appeal, the old live oaks are in trouble in Louisiana, subject to increasingly violent storms, a rising coastline, invasive non-native termites, changing weather patterns, and little or no protection from unrestrained development. But what can’t be saved can be preserved in a photograph and a story.

For more than four decades, I’ve photographed and gathered stories about Louisiana’s historic and notable oaks. Since Hurricane Katrina, I’ve focused on the oldest oaks in Louisiana because I’ve sadly observed that their numbers decline each year. These tree portraits become a visual and written record of a life that stretches across centuries. By sharing these photos and stories, my hope is that we might all gain a greater appreciation of the beauty and mystique of the old oaks and help them survive into another century.

Seven Sisters Oak, Mandeville

In the quiet historic community of Lewisburg, now a neighborhood of Mandeville, on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain, lives the Seven Sisters Oak. Originally named Doby’s Seven Sisters by the Doby family living next to it, this massive tree, estimated to be between 500 and 1,000 years old, is the current president of the Live Oak Society and for more than a decade also held the title of National Champion Live Oak in American Forests’ National Register of Big Trees before an even larger tree was measured in Georgia.

In her book Louisiana Live Oak Lore, Ethelyn G. Orso recalls a story about a Catholic missionary from New Orleans who preached the gospel to a group of Choctaws under the limbs of the Seven Sisters Oak. For years, the eligibility of the ancient tree to the Live Oak Society was disputed because it was believed to be several separate trees growing together. In 1976, after inspection by federal foresters, the tree was stated to have a single root system and was registered into the Live Oak Society as president due to its extraordinary size and age. Its inauguration was celebrated with a visit from then governor John McKeithen. Attendees, who enjoyed performances by the United States Marine Band and a ballet troupe, received wooden doubloons with an imprint of the tree’s name on it.

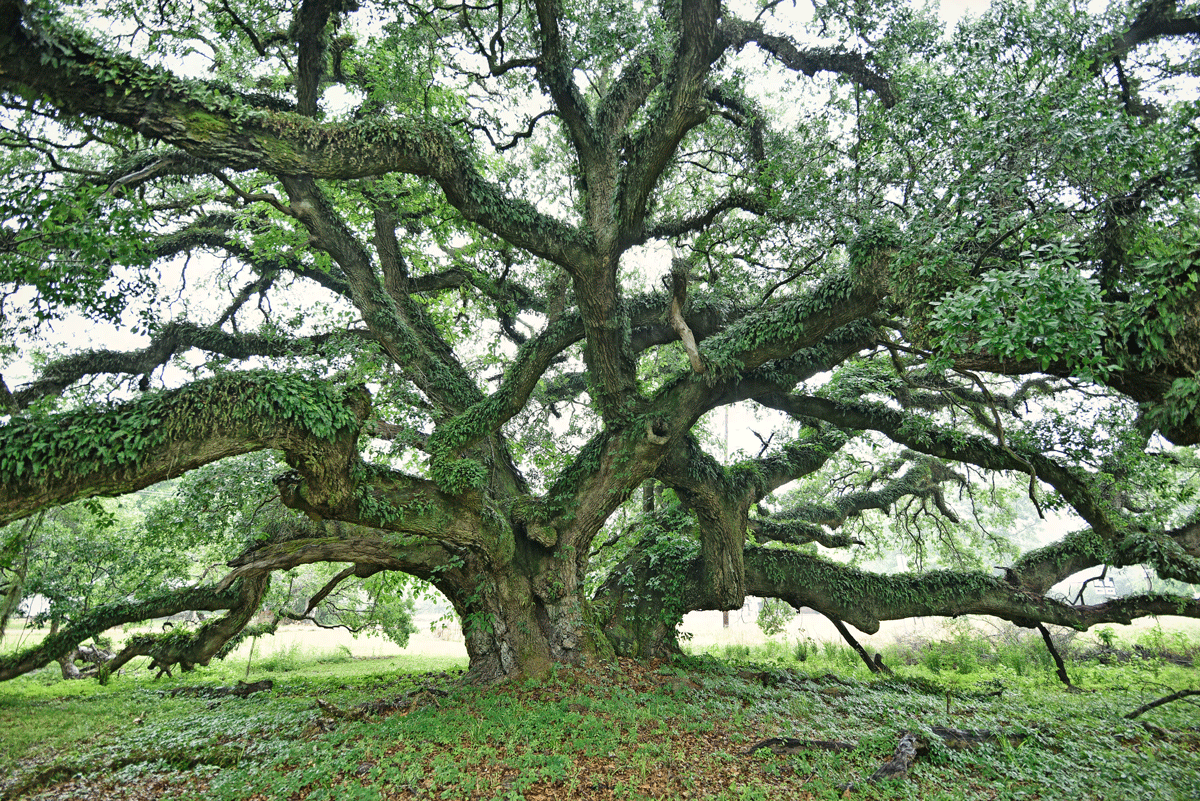

Cathedral Oak, Lafayette

The Cathedral Oak in Lafayette. Photo by William Guion.

Located on the grounds of the Cathedral of St. John the Evangelist in the heart of downtown Lafayette, the Cathedral Oak is the second vice president and a founding member of the Live Oak Society. In 1821 Jean Mouton, an Acadian refugee and owner of Vermilionville Plantation, donated the land and the old oak to the church parish. According to the cathedral’s website, the first pastor, Michel Bernard Barrière, may have requested this specific site from Mouton because of the towering live oak located there. The tree could be between 300 and 400 years old.

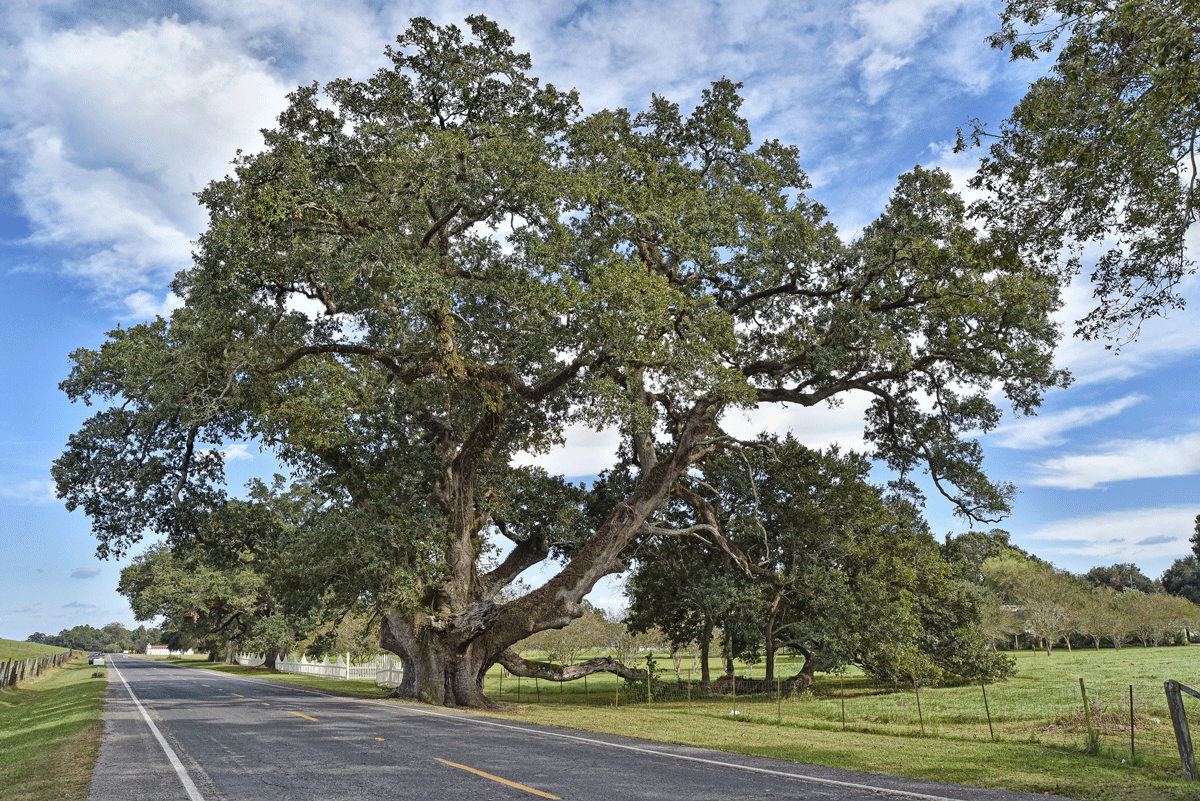

Lorenzo Dow Oak, Grangeville

The Lorenzo Dow Oak in Grangeville. Photo by William Guion.

The Lorenzo Dow Oak is named after an eccentric itinerant America preacher who lived between 1777 and 1834. Dow traveled widely around the United States, mostly on foot, preaching in a dramatic fire-and-brimstone evangelical style and living like a pauper with only the clothes on his back and a box of bibles. During his lifetime, his autobiography was among the most-read books in the country. He traveled through north-central Louisiana circa 1803–1804. Because he was unwelcome in established churches, Dow would preach in town halls, barns, open fields, and under the sheltering branches of a live oak tree.

Stonaker or St. Maurice Oak, New Roads

The Stonaker Oak in New Roads. Photo by William Guion.

This old oak was possibly John James Audubon’s favorite. While employed as a tutor at Oakley Plantation near St. Francisville, Audubon began work on at least thirty-two of his famed paintings of North American birds. He would cross the river regularly via the Pointe Coupee ferry to hunt birds. The St. Maurice Oak was about a mile upriver from the ferry landing and a few hundred feet from the Labatut family home where Audubon was a welcome guest. According to an article in the Louisiana Conservation Review, Audubon “undoubtedly sheltered under the oak on hot days” and was fond of the old tree and the shade it offered.

Photographer and writer William Guion has written six books, a blog, and multiple articles about oak trees and the history associated with their location. His most recent book, Return to Heartwood—A Search for the Heart of Live Oak Country, offers a retrospective in photos and essays of his four decades observing Louisiana’s live oak trees. You can find more live oak portraits and their stories at 100oaks.blog.