Fall 2016

Seeds of a New Science

LSU’s hatchery is designed to produce around a billion larvae each year, which will grow into edible oysters

Published: September 1, 2016

Last Updated: May 2, 2019

“I don’t drink beer,” Supan announces to the farmers. “So you can pay me back with a bottle of wine. Or two.”

Dr. Supan benevolently lords over a slice of paradise on Caminada Bay, including a massive waterfront laboratory for breeding genetically perfect oysters, and a private floating farm in which to grow them, consisting of rows and rows of what look like miniature shark cages. Only Supan has official clearance to trout fish between the cages, which he does, alone, at 5:30 every single morning. “I only throw top water lures,” he tells me when I express jealousy. “You don’t catch as much but when you do they’re the biggest and best.”

The pinky-nail-sized larval oysters look like a pile of mushy sand until Supan’s crew rinse and separate them from each other. The tiny oysters yearn to attach to anything, but each of these will live its entire life autonomous and untethered from rocks and fellow oysters.

In the process of packing the seeds into small sacks of 50,000, three of the tiny larvae fall to the ground. This goes unnoticed by no one. The farmers purchase the two-millimeter larvae through the Louisiana Oyster Dealers and Growers Association for $300 per million, or $11 per thousand. Traditional oyster larvae face all manner of challenges, and most never make it to adulthood, but the cage farmers expect almost all of these seeds to grow.

Marcos Guerrero and his son Boris return their triploid oysters to Caminiada Bay to continue growing. Photo by Rick Olivier.

LSU’s hatchery is designed to produce around a billion larvae each year. Seed is what Supan and company focus on, because seed is what’s been desperately needed. Jules Melancon, a third generation oyster fisherman, was the first Louisiana farmer to adopt this cage technology six years ago. “We still get a few hundred acres of wild oysters, but only about every three years, “says 58-year-old Melancon, who joined the family business at age 11. “So, we have to have a seed crop too every year to have the big money. And usually you’d lose a lot to predators, so you need a lot of seed. This way, LSU grows the seed, and the cages protect from predators.”

Gripping two small, wet sacks of larvae that, ideally within the year, will translate into hundreds of fat sacks of edible oysters, new farmer Scott Maurer of Cocodrie explains to me, “They are safer in the cages, so they’re happier oysters, and that means they spend their energy creating more meat instead of more shell.”

Maurer, a self-professed “oyster nerd,” describes the flavor of his cage-grown oysters the same way one would wine: “You get that briny taste up front,” he says, tilting up an invisible oyster shell, “and then a buttery sweetness in the finish.”

Once all the farmers have collected their seed, Dr. Supan climbs down a wooden ladder and wades into Caminada Bay, out the back of the laboratory, to begin removing from the water several big mesh bags full of “broodstock” — the big oysters used to make more seeds. “We have two rules here,” Supan shouts across the water to the hot dock where I remain dry, save faint sweat. “Rule one: don’t get hurt,” he says. “And two: Don’t eat the broodstock. These oysters are probably worth a hundred dollars apiece in grant money.”

“Our oysters, when we harvest, all go from the farms to the cooler in under an hour. They say you should only eat oysters in months that have an R in them. We say refrigeration is the new R.”

Supan pulls the heavy bags from the cages, rolls them onto the dock, and then hauls them in a wheelbarrow to a table under the shade of the raised house where he lives during the week. Loose, living broodstock oysters pour out of the grungy sacks onto the table, along with hundreds of baby fish, crabs and conch mollusks. Supan plucks up one particularly big mollusk and gives it a disparaging look.

“These things eat oysters,” he tells me. “And I am a high priest in the Knights of Mother of Pearl. That’s a not so secret society dedicated to killing anything that would harm an oyster. So…”

Frowning, he tosses the mollusk back into Caminada Bay.

As Dr. Supan and an assistant from Wildlife and Fisheries scrape and polish each individual broodstock oyster on the table, Dr. Supan’s Ph.D. student Brian Callam is lucky to remain inside, in the much cooler oyster laboratory.Today Callam keeps a close eye on the “spawning rack” — a wall of small tanks, like those made for betta fish. These tanks hold one oyster apiece, each of them facing forward in a way that anthropomorphizes their craggy mouths. They all seem to wear the disgruntled expression of someone on the phone with a telemarketer.

“We mate a four chromosome male oyster, a tetraploid, with a two chromosome female oyster, a diploid, which creates a three chromosome oyster called a triploid,” explains Callam. Like mules, he says, selective breeding makes them bigger and stronger, but unable to naturally reproduce.

And so here Callam stands before the spawning rack, hoping to collect unfertilized eggs. He’s tried different ways to nudge them into spawning, mostly hitting them with a little hot water to get them excited until the males start leaking milky fluid and the females begin clapping to release their eggs. Callam will heat up the sperm to sterilize it and then use it for its pheromones, which will further encourage the oysters to spawn.

LSU doctoral candidate Brian Callam helps oysters spawn in the spawning rack. Photo by Rick Olivier.

As the sun hints at relenting for the day, Dr. Supan dips back in the water to show farmer Marcos Guerrero a new set of oyster cages designed in Australia. “Coincidentally, the floating cage technology we usually use was invented in Acadiana…Canada,” chuckles Dr. Supan. “The inventor’s name is Rhéal Savoie, if that doesn’t sound familiar enough to Louisiana ears.”

Farmer Maurer comes outside with me to watch them, and to explain to me how LSU’s triploids defy the rules of eating oysters in the summertime. “In the warm weather months traditional oysters get thin and milky, because they are spawning,” says Maurer. “Through the whole long summer they are either spermy, or else they’re spent and skinny. Until in winter, they start to store fat again, so they can spawn come summer.” With spawning taken out of the triploids’ lives, he attests, the product retains a good size and consistency year-round.

“Also in summer, I don’t necessarily want to eat oysters that have been sitting in the hot deck of a boat for eight hours,” Maurer adds. “Our oysters, when we harvest, all go from the farms to the cooler in under an hour. They say you should only eat oysters in months that have an R in them. We say refrigeration is the new R.”

Marcos Guerrero boats us out to his oyster plot in the Grand Isle Oyster Farming Zone administered by the Grand Isle Port Commission. The plot isn’t as luxuriously close to land as Dr. Supan’s, but still near enough that Marcos always meets his goal of refrigeration within an hour of harvest.Guerrero must do a bit of construction on the side as he awaits his third oyster crop. He previously raised organic sugar cane, but then legislation passed in 2012 lifting the long-loathed moratorium on Louisiana oyster leases and approving a new “marine enterprise zone,” which consisted of eight, two-acre oyster farms. Marcos’ lease was granted in 2013, and in 2014 he started planting and floating cages. His first harvest came in 2015 and his second in 2016.

Marcos’ son Boris, who boasts a master’s in economics from LSU along with a bachelor’s in computer science, says he is on board the boat because the economics of cage farming shake out. More importantly, he’d rather work a job that doesn’t involve staring into a computer. Still, while his father wears a short sleeve wetsuit to work on the water, Boris wears a mauve office dress shirt under khaki rubber chest-high waders.

Usually, father and son drive out to harvest oysters, but today they’re putting oysters back. Seven of their cages detached and sank to the bottom, where the mud suffocated the bottom layer of precious triploids. They retrieved and removed the dead, cleaned off the living and are now placing them back safe in their cages.

Marcos’ cages emerge from the water heavier each time, caked in new barnacles and algae. “They’re made of PVC and were guaranteed for five years. But after only three years we’ve seen some real deterioration, so that’s another expense we didn’t count on,” says Marcos. “And then two cages were stolen recently — luckily they only got two. They were trying to take a whole line of cages, ten cages.” Full of oysters, he says the cages were worth $700 apiece, not including labor.

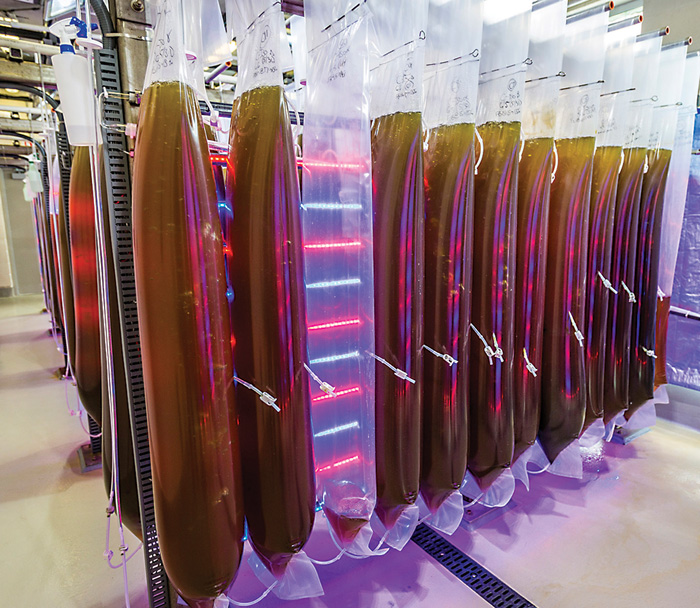

Giant tubes of algae are brewed on premises to feed Dr. Supan’s special oysters. Photo by Rick Olivier.

In terms of setup cost, Guerrero also had to retrofit his warlike, metal boat with a water tank, a massive Bimini top and two motors: one extra to operate the new hydraulic wench that lifts the oyster-gorged cages from the water.

Marcos’s oysters look big enough to be harvested, but they’ve been out of the water a long time and he wants to dunk them for a few more days to ensure his product can be categorized as elite “white tag” oysters. Boris admits, “Maintaining the white tag is a lot of extra work.”

When asked to quantify his newish investment, Marcos shakes his head: “I can’t even think about it,” he says. “We have to succeed, and it doesn’t matter the time it takes, or the effort.”

Nevertheless, Jules Melancon later tells me cage farming costs him far less than the traditional method of purchasing and dumping large rocks on an oyster lease and hoping for the best. “Not including the cost of the manual labor, a barge load of rocks can cost millions of dollars, and then you’re gambling on a catch,” explains Melancon, who says it’s not unusual to lose well over half the oysters you might plant. “And if the fishermen do get lucky, and oysters stick to their rocks, they can only harvest once or twice before the rocks gotta all be turned over, or else coated in lime — both expensive procedures.”

Replacing the oysters back in their cage and locking the door, Boris says with a sigh, “Everything grows so fast here.” He knows returning this batch to the water will give the oysters the chance to grow beyond the bite-sized delicacies beloved by their high-profile New Orleans clients like the Curious Oyster Company at St. Roch Market or Commander’s Palace. Who wants oysters you can’t fit into your mouth?

“Texas. We sell them to Texas,” says Marcos. “They like them big as steaks. We are lucky to have that market.”

Exposed to the heat and sun even briefly, Marcos’s dank cages smell strongly of ocean life. “Caminada Bay itself is so full of flavor,” he says, inhaling a sample. “It shows in the oysters. They’re beautiful. They’re different.”

His son Boris pushes another cage full of oysters off the boat, and the water below softly explodes in a beautiful green cloud of sea creatures and organic matter that looks, frankly, delicious.