Democracy & Media

Mardi Gras Canceled

Ernest “Dutch” Morial and the 1979 New Orleans police strike

Published: December 3, 2018

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

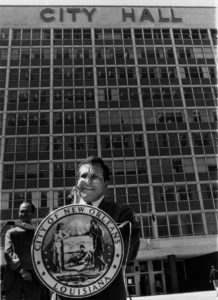

Photo by Harold F. Baquet, the Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Harold F. Baquet and Cheron Brylski, 2016.0172.3.46

Ernest "Dutch" Morial in front of City Hall.

This article is part of the “Democracy and the Informed Citizen” initiative, administered by the Federation of State Humanities Councils. The initiative seeks to deepen the public’s knowledge and appreciation of the vital connections between democracy, the humanities, journalism, and an informed citizenry. The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities thanks The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for their generous support of this initiative and the Pulitzer Prizes for their partnership.

For the residents of New Orleans, Mardi Gras is just as important as any national holiday—an opportunity to see friends, let loose, let the good times roll. For the City of New Orleans, Mardi Gras is also important—a time to generate revenue while demonstrating to the world that New Orleans is rich in culture, strong in pride, and committed to the safety of its residents and tourists.Canceling Mardi Gras is thus almost unheard of in New Orleans. Sometimes there are circumstances beyond the control of the city; parades, understandably, did not roll during the Civil War, World War I, the Korean War, and World War II. The outlier: the 1979 Mardi Gras season, a casualty of a different kind of war, one waged between then Mayor Ernest “Dutch” Morial and the Teamster-affiliated Police Association of New Orleans (PANO).

In 1978, Morial became the first African-American mayor of New Orleans. Within the first year of his tenure, Morial faced an inherited budget crisis of forty million dollars, threats of strike from city employees, and resistance from both black and white groups in the city, who for various reasons felt the new mayor did not serve their interests. Even the local media was skeptical of Morial. To some, he was viewed as a wild card. He was an unpredictable politician whom the States-Item staff writer Walter Isaacson described as “too defensive.”

The media’s love-hate relationship with Morial began almost immediately after his election as Mayor of New Orleans, when he chose to call out the media at his January 17, 1978, address to the Metropolitan Area Committee. Morial stated that the media needed to become “much more responsible in providing us with better-balanced and less mystifying news coverage and analysis if we are ever to achieve a more rational understanding of the city’s problems by the general public.” Morial accused the media of providing an “extremely shallow and ‘over-glowing’ news reportage, particularly emphasizing tourism and sports.” He challenged the media to report the good with the bad and the ugly of the city’s issues, no sugar coating necessary.

Arguably, what Morial really wanted was for the media to report the shortfalls of the previous Mayor, Moon Landrieu. He wanted the citizens of New Orleans to know that his administration had inherited a fiscal shortfall of forty million dollars and that his administrationwould have to make cuts to the budget that would more than likely not sit well with many of his critics.

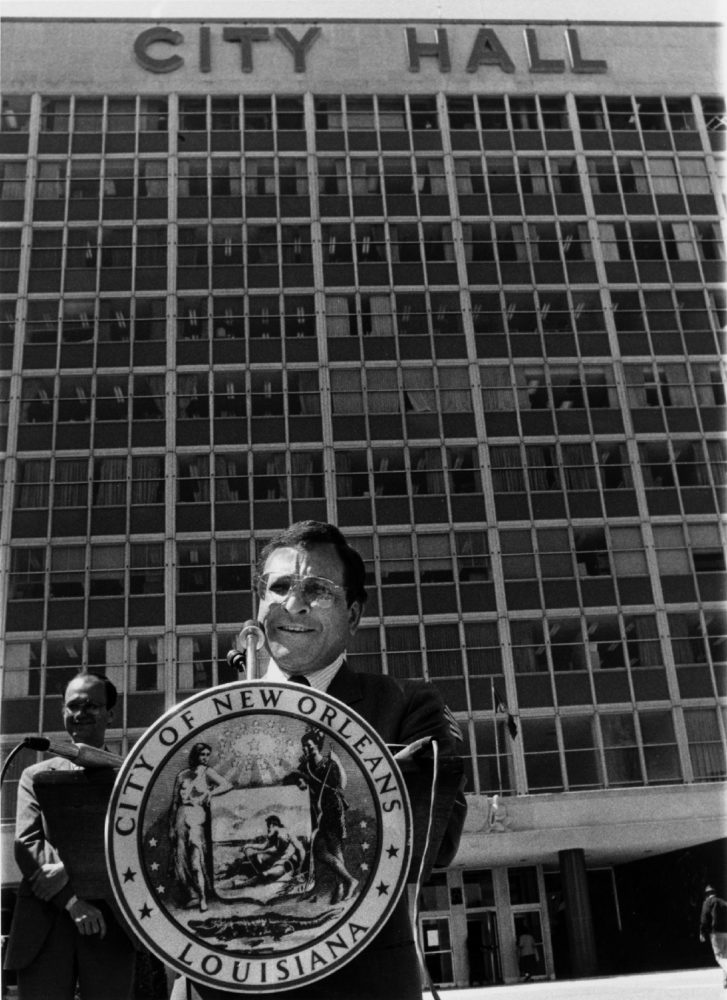

A National Guardsman posted outside the New Orleans Police Department’s 1st District Station. Photo by Patrick McKee. The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1988.110.6

One of the first tasks of Morial’s new administration was finding a superintendent of police. Morial stated that the new superintendent would be in charge of reorganizing the police department to maximize its efficiency and streamline its control. At the end of 1978, Morial boasted that despite the budget crisis, his administration proposed the highest pay increase for policemen in modern times, and that both the Civil Service Commission and the City Council approved the pay plan and its implementation.

What Morial failed to mention was that his plan only reallocated existing funds. These funds were freed up by cuts to sick leave benefits and vacation days of all civil service employees, including the police. While the police pay raise garnered positive media attention for the mayor, the reallocation of funds did not go over well with police officers, who were represented by two competing unions, the Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) and the Teamster-affiliated Police Association of New Orleans (PANO). PANO took the lead in voicing concerns about the new policies affecting NOPD.

Meanwhile, Morial continued his task of searching for a superintendent of police. Eventually he chose James C. Parsons, an “outsider,” but a respected former police chief and administrator from Birmingham, Alabama. Many police officers felt that Morial ignored several qualified candidates within the ranks of the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD). This, along with the pay raise issue and the fact that Parsons began reorganizing the police department almost immediately after he was hired, left many in the NOPD feeling disdain for the mayor and Superintendent Parsons.

Yet PANO, led by officer Vincent Bruno, asked Superintendent Parsons to support them in their efforts to negotiate a salary increase. Parsons did so by recommending to Morial that thecity consider extending even greater salary raises. The city refused to negotiate with PANO, resulting in PANO threatening a police strike. On January 4, 1979, PANO members held a meeting in which they voted to have a strike tentatively scheduled before the 1979 Mardi Gras season.

Morial took the threat rather lightly. In an article written by Morial and published in the January 1979 volume of the Journal of Commerce, titled “The New New Orleans,” Morial invited the world to visit New Orleans, stating,

Though I can’t promise that the hotel rooms will still be available for this year’s Mardi Gras, I can say with certainty that more visitors than ever will enjoy the ‘Greatest Free Show on Earth,’ and many will enjoy it while staying in one of the more than 7,000 new first-class hotel rooms recently built in downtown New Orleans.

Morial, who characterized PANO as a small group run by “radicals,” assumed that the organization lacked sufficient police support to make its strike threat a serious issue for the 1979 Carnival season. He instead promoted Mardi Gras in keeping with a promise he made to the Tourist Commission at its annual meeting in September 1978. At the meeting, Morial praised the tourist industry, calling it “one of the main lifelines of the city.” He vowed that his administration would work with the tourist industry to continue to foster its growth, noting that tourist expenditures in New Orleans generated $230 million in wages and salary income and created nearly forty thousand jobs for Orleans Parish. The taxes paid by travelers to New Orleans alone totaled $27.4 million, all of which went back to the residents of New Orleans through public services like police security, sanitation, fire protection, health care, education, recreation, and more. According to the Chamber of Commerce, Carnival season alone typically generated $250 million in business revenue. Morial and most residents believed that the NOPD and the city would come to an amicable agreement that would prevent the loss of revenue before Mardi Gras, the highest money-making event in New Orleans. After all, the majority of police officers who were employed by NOPD were citizens of the city who benefited from the revenues made during Carnival season.

On February 8, a little over a month after the first PANO strike meeting, PANO members voted unanimously to strike, which went into effect immediately. The following day, the mayor’s office petitioned for and received an order from a Civil District Court Judge, ordering striking policemen back to work. Morial than released a press report assuring the citizens of New Orleans that all “necessary” steps were being taken to guarantee the safety of the city during what he called “this illegal work stoppage by Teamster affiliated police officers.” Morial went on to say that these police officers had abandoned their sworn duties and turned their backs on the people of New Orleans, all because the city signed an agreement recognizing the FOP as the official bargaining agent of police officers and not the Teamster-affiliated PANO union.

According to Morial, PANO wanted citizens to believe the strike was over salary increases, but Morial argued it was not. He appealed to the citizens of New Orleans through a press release written for news and media outlets, saying, “I am sure that most citizens feel as I do. I simply do not understand why the police officers have quit their jobs and turned their backs on the very citizens who are paying higher taxes to fund the 15 to 30% salary increase . . . for all police officers.” Thirty hours later, the strike ended with Morial recognizing PANO as the exclusive bargaining agent of NOPD, amnesty for strikers, and restoration of reduced leave benefits, among other demands. The city let out a sigh of relief as the first-ever NOPD strike was over, and Mardi Gras was back on. Or so they thought.

With the success of the first strike and Mardi Gras two weeks away, PANO decided to continue seeking concessions from the city, with new demands that would essentially give the Teamster union more control over management of the NOPD. PANO gave the mayor and the city less than a week to agree to the new demands, or a second strike would take place that could potentially cancel Mardi Gras, scheduled for February 27, 1979. In addition to regional coverage from the Times-Picayune and Baton Rouge Advocate, national papers such as the Washington Post and New York Times ran multiple stories covering the events that followed.

Morial appealed for the Louisiana National Guard to police Mardi Gras, only to have his hopes crushed by Governor Edwin Edwards, who urged Morial “to cancel Mardi Gras parades in the event of police action,” saying “it took police experienced in crowd and law enforcement to deal with Mardi Gras.” Edwards had articulated what everyone was thinking. There was no alternative to using NOPD for crowd control and protection of residents and tourists during Mardi Gras.

The front page of the Times-Picayune for February 16 read “Strike Can Be Avoided”; that same day, the Baton Rouge Advocate published an article titled “N. O. Mayor Makes Arbitration Offer.” According to the article, Morial offered to enter into “personal binding arbitrations” on financial matters as far as the law allowed. Morial explained that he could not bind the city to arbitration, but he would do what he could to convince the City Council to follow the decision of the arbitrator if contract demands were left pending after Mardi Gras. Morial suggested a cooling-off period until March 5, with negotiations continuing until April 15. In his parting shot, he noted that if Mardi Gras were canceled, all fault would rest with PANO.

In the midst of all of the back-and-forth press about the threat of canceling Mardi Gras, the citizens of New Orleans chimed in. In the Times-Picayune article “City Can’t Afford Strike, Group Warns,” the Concerned Citizens of New Orleans wrote “another police strike means police will be breaking the law and presenting New Orleanians with a $40 million price tag.” The group went on to say that canceling Mardi Gras “will give our city a world-wide black eye.” Morial appealed for the Louisiana National Guard to police Mardi Gras, only to have his hopes crushed by Governor Edwin Edwards, who urged Morial “to cancel Mardi Gras parades in the event of police action,” saying “it took police experienced in crowd and law enforcement to deal with Mardi Gras.” Edwards had articulated what everyone was thinking. There was no alternative to using NOPD for crowd control and protection of residents and tourists during Mardi Gras.

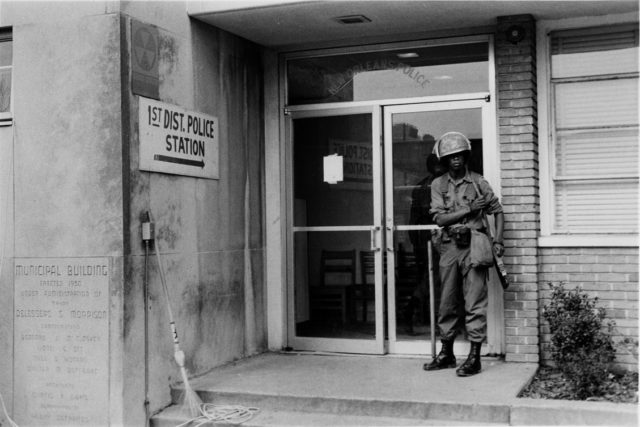

Picketers gather near the parish prison and criminal courthouse. Photo by Patrick McKee, the Historic New Orleans Collection, 1988.110.2

One police officer told the Times-Picayune, “I’ve got a kid who likes Mardi Gras parades, but I guess that’s tough. That’s just real tough. We’re holding the cards and you don’t fool around with four aces.” As things heated up in the city, newspapers ran headlines like “Wanted: Guns, Guards, Locks,” “Carnival Outlook Gloomy,” and “New Orleans’ Carnival Atmosphere Chilled by Police Strike.” Striking police officers burned their uniforms in front of news cameras, slashed the tires of non-striking police, and egged Morial’s home. Even television media representatives would fall victim to the chaos; during a press conference with PANO president Vincent Bruno, local newsman Bill Elder got into a physical altercation with a press photographer, whom Elder accused of blocking his television monitor.

In the end, the decision regarding that Mardi Gras season was made, in large part, not by the mayor, nor by NOPD and their representatives, but by community members who had a vested interest in the fate of Carnival season for 1979 and years to come. The captains of some of the city’s most prominent Carnival krewes came together and voted to cancel their parades, saying they would not allow the festival to be held “hostage” by the striking police. The February 21, 1979, headline in the Baton Rouge Advocate read, “All Parades Canceled in New Orleans,” and the Times-Picayune headline read, “Captains Cancel Mardi Gras.” The captains said, “It is wrong to use Mardi Gras as blackmail in this dispute. The same procedure can be used each year and we are not going to let our organizations be puppets in such a plan. Therefore, we cancel our parades in New Orleans.”

The Times-Picayune ran a front-page editorial in conjunction with the featured headline, titled “City Under Siege.” The editorial blamed the cancelation of Mardi Gras on the strikers, stating, “[T]hey are wrecking themselves in the eyes of the very public on whom they are dependent for the tax dollars needed now and in the future.” The public was furious over the cancelation of Mardi Gras, blaming PANO and complimenting Morial on an excellent job in trying to end the strike and save Mardi Gras. One resident said, “I’m mad as hell . . . I did sympathize with the police but I think they’ve jumped higher than they should have.” The strike ended on March 3, 1979, when police officers broke the strike and returned to work prior to union negotiations. This left the city and Morial with the upper hand in dealing with both punishments and concessions to NOPD.

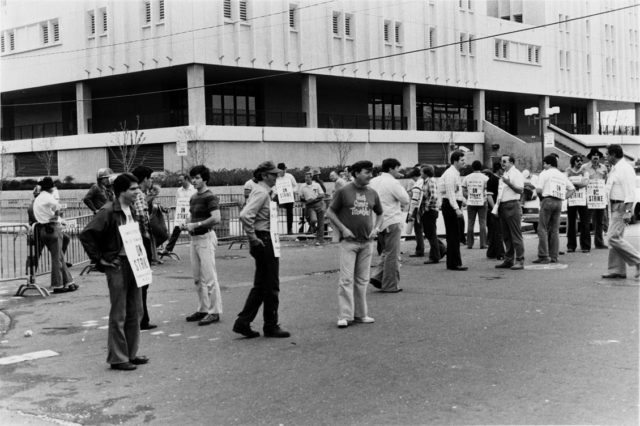

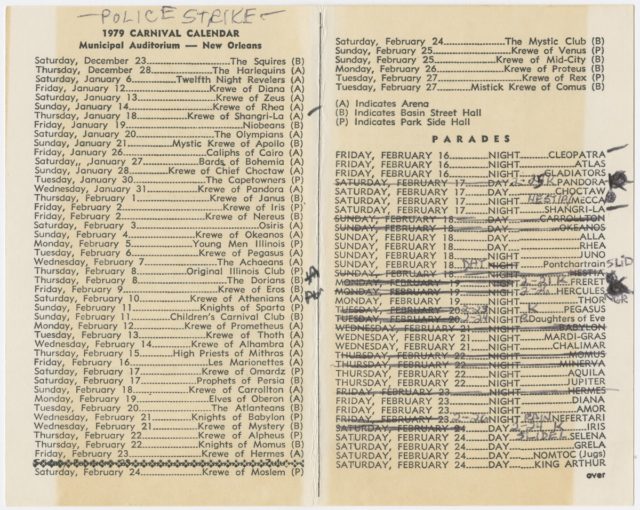

Carnival ball and parade schedule showing strike-related cancellations. The Historic New Orleans Collection, 2000.34.277

The 1979 cancellation of Mardi Gras will go down in history as the first and only Mardi Gras canceled due to a strike. Yet despite this debacle, Morial, the city’s first African-American mayor, was able to garner the trust of the community to the extent that he was elected to lead the city for a second term.

It must be noted that, in true New Orleans fashion, the official cancelation of Mardi Gras did not, in the end, stop the party. The New York Times said it best in an article they published on Ash Wednesday of that year—“Mardi Gras 1979: Lot of Spirit but a Little Less Fat.” The article expressed how important Mardi Gras is to the people of New Orleans, noting, “Cancel Mardi Gras? You might as well try to cancel Christmas.” There were no great institutions running the party—not the city, not the elite Carnival krewes, and not the police force. But still, decked out in costumes, feathered boas, and beads, residents took to the streets; they took it upon themselves to create their own impromptu parades with neighbors, friends, and strangers alike. Some even said that the 1979 “unofficial” Mardi Gras was the best Mardi Gras they ever had.

Dr. Sharlene Sinegal-DeCuir is an Associate Professor of History at Xavier University of Louisiana. Her areas of concentration are in American, African-American, and Latin American history. Throughout her academic career, she has focused on the New South period of American history through the Civil Rights Movement, with particular interest in African-American activism in Louisiana.