MR-GO: A “Miracle” Mired in Controversy

Dug a half-century ago as a shortcut for oceangoing vessels, the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet has become an environmental disaster

Published: July 28, 2015

Last Updated: August 28, 2020

Aerial view of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet

Heralded as “one of the miracles of our time,” MR-GO was not only seen as a navigational expressway, but savior of the aging port of New Orleans. Mayor DeLesseps S. “Chep” Morrison said that it “will have the effect of bringing another Mississippi River to New Orleans … that will be safer and cheaper to maintain.” Neither the mayor, nor any of the dignitaries present could foresee how such a “miracle” would sour and become embroiled in nearly a half-century of not living up to expectations and creating environmental problems not even contemplated in the 1950s.

Man-made waterways serving as shortcuts between New Orleans and the Gulf were nothing new in 1957. Although New Orleans was founded at a strategic point on the Mississippi River, its proximity to Bayou St. John and Lake Pontchartrain with their connection to the Gulf was used from the start as a shorter, safer route to the sea than the treacherous, ever-changing river.

To enhance the lake/bayou route in the 1790s Governor Francisco Luis Héctor de Carondelet ordered construction of the Carondelet (Old Basin) Canal between the tip of the bayou and modern Basin Street. Four decades later, the New Basin Canal was dug on the site of today’s Westend Boulevard and Pontchartain Expressway. Although both canals are now memories, they were once integral parts of maritime New Orleans carrying substantial amounts of trade to the city from the north shore of Lake Pontchartain and other Gulf ports.

In the 19th century a canal at Violet in St. Bernard Parish was built between the river and Lake Borgne, but still the city’s long held dream of connecting the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain with a navigation canal did not came to fruition until the Industrial Canal was dedicated in 1923. The president of the Hibernia Bank called it, “the boldest and most progressive stroke ever undertaken in port affairs.”

Each canal was a step in providing easier access to the port of New Orleans, while also avoiding the bothersome lower reaches of the Mississippi. None of them provided the wished for direct route between the city and Gulf, although as early as 1826, planners advocated such a canal. In 1875 a plan for a deepwater canal and lock starting at Breton Sound was proposed. At the time the passes to the Mississippi River were blocking up with silt and hindered shipping. Instead of a canal, the Eads Jetties were built at the southwest pass of the river which eliminated the troublesome problem of silt buildup. The dream of a Gulf outlet did not end here, and with the digging of the Intracoastal Waterway in the 1940s such a project became more attainable.

A Shortcut to the Gulf

The Intracoastal Waterway was the idea of Texas banker Clarence Holland and railroad man Roy Miller. In 1905 Holland arranged a meeting between business and port leaders from Texas and Louisiana to discuss the merits of an inland waterway connecting the states’ rivers, tributaries, bayous and ports. Initially the proposal progressed slowly. Finally with passage of the federal River and Harbor Acts of 1925 and 1927 construction of a 9-foot deep, 100-foot wide barge canal between New Orleans and Corpus Christi was authorized.

The secure position of the canal became apparent during World War II when barges safely moved through the protected inland route within sight of marauding German U-boats. As a result, Congress approved the expansion of the canal in 1942 to 12 feet deep and 125 feet wide. It was also extended southwest to the Rio Grande and east through Florida. The expansion also passed through eastern New Orleans intersecting with the Industrial Canal.

With the expansion of the waterway through New Orleans the possibility of a river outlet seemed attainable. Such a canal was proposed by Lester F. Alexander, a successful boat builder and engineer who was familiar with the vagaries and dangers of the lower Mississippi. He proposed a tidewater seaway cutting through the wetlands of eastern St. Bernard Parish not far from the shores of Lake Borgne. He was convinced that silt accumulation would not be a problem in the canal, and at last the long held dream of ships avoiding the hazards of the river would be realized. Appointed by Louisiana Governor Sam Houston Jones in 1940 to the New Orleans Board of Commissioners — the Dock Board — Alexander was put in an ideal position to promote his tidewater canal and from this the Tidewater Canal Association was created.

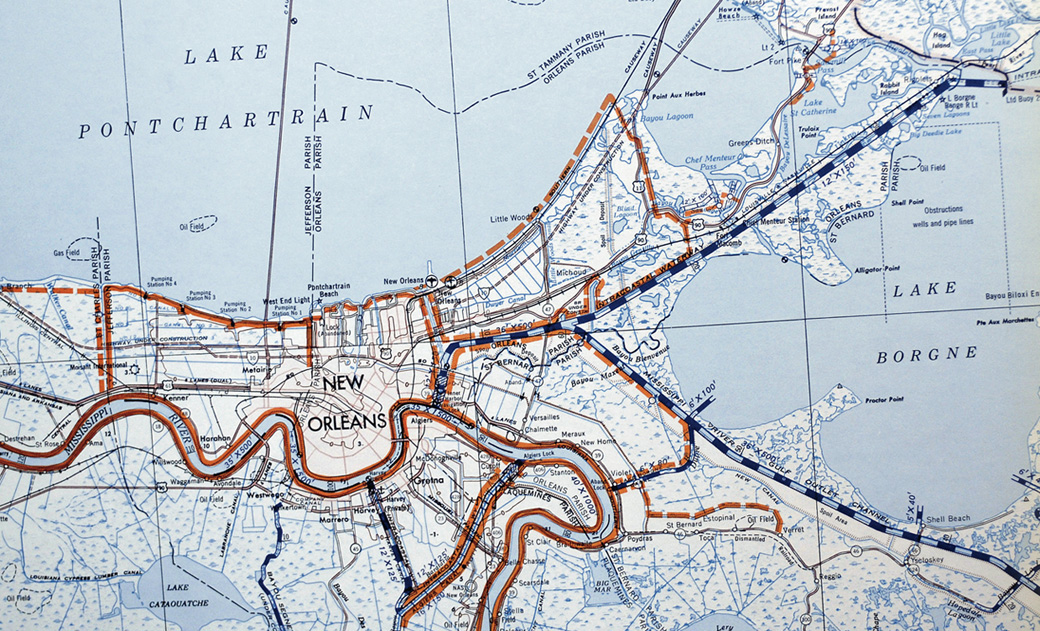

A U.S. Army Corps of Engineeers map from 1965 depicts the Misissippi River Gulf Outlet, forking southeastward from the Intracoastal Waterway.

Alexander arranged public hearings in 1943 and 1947 to demonstrate the merit and feasibility of his proposal to the business community and the Army Corps of Engineers. After the first hearing in 1943, the Times-Picayune applauded the plan as a “Vital Needy Tidewater Channel.” M.A. Mathieson, vice-president of the Standard Oil Company urged that the canal be built, since, “the Mississippi River is a nightmare to all of us.” Andrew J. Higgins, successful New Orleans builder of PT boats and landing craft for the US Navy in World War II, was quoted as having advocated such a canal for many years.

The canal was also seen as an important step in improving New Orleans’s position and prestige as a world trade center. The city undeniably possessed one of the world’s greatest and most strategic ports in the mid-20th century, but the port’s position was slowly being whittled away. In 1803, American control of the port of New Orleans was of paramount importance and led up to the Louisiana Purchase. This allure diminished over time especially as competition grew stiffer among Gulf ports. This was most evident of Houston which did not even have a port until the 50-mile long Houston Ship Channel opened in 1914. The booming city not only had access to Galveston Bay and the Gulf, but became New Orleans’ chief rival as the nation’s second biggest port in tonnage. If Houston could have a canal — why not New Orleans?

The port of New Orleans was regarded as a laggard partly because of its hazardous water route. Louisiana Senator Allen J. Ellender expressed fears that its port facilities were not only antiquated, but that the cost of shipping cargo up the river would end up being greater than if a canal were used. If an adequate canal was built, Louisiana Senator F. Edward Hebert felt confident that, “New Orleans would enjoy unprecedented growth.”

The Corps of Engineers was responsible for designing and building the project, but would not recommend it unless local support existed, which was not difficult to muster. The city’s top business and civic leaders were virtually unanimous in their praise for the project. Not only was it shorter than the traditional river route, but its maintenance was expected be of little concern, since it was supposed to be free of shoaling, currents or difficult turns. There were also starry promises of large parcels of land becoming available along its route. These would be ripe for industrial and port development away from the congested riverfront, which could be redeveloped for non-industrial uses. This was enough for the Corps of Engineers who decided that the St. Bernard Parish site would be the ideal one for the seaway — although in 1943 Jefferson Parish officials had unsuccessfully pushed for it to be put through their parish.

Vital To National Defense

After having been shelved for the duration of World War II, MR-GO gained momentum in 1948 when President Harry S. Truman gave it his full support. Congress, however, did not approve it then, since there were other national factors at play — most importantly Congressional debate over the St. Lawrence Seaway. Upper Mississippi business leaders were more concerned about the potential benefits of this huge project, and for the time being ignored MR-GO. When the St. Lawrence project was approved in 1954, attention then shifted southward to MR-GO amid vigorous lobbying.

In 1955, Walter C. Pioser of St. Louis and head of the Mississippi Valley Association called the New Orleans canal project, “Vital to All Valley,” because of its economic value. He confirmed that it was the association’s “number one recommendation.” As to its $70 million estimated cost, Everett T. Winter, vice-president of the association, said, “The project has a favorable benefit ration to cost,” and that it would be a, “benefit [to] all water transportation using … New Orleans.” He also believed in MR-GO’s, “importance to national defense.”

MR-GO’s professed importance to national security became a major selling point. In 1943 it was called as an essential component of the United States’ new position as a world naval leader — that would be further enhanced after the end of the war. Louisiana Senator John H. Overton was quoted in the Times-Picayune as saying, “What are fighting ships without port facilities? This great city … should have her navigation keep pace with the expansion of a new area ….” In 1955 Tennessee Senator Albert Gore reiterated this when he supported the canal as, “important to national defense,” adding that, “within my lifetime [it will] make New Orleans the first port of the United States.” A year later, when MR-GO was up for Congressional debate — and the Cold War with the Soviet Union was the land’s greatest fear — the Times-Picayune editorialized that the canal, “conforms with the idea of strategic interdependence and of national security …. This port is vital to national defense [and] the outlet … has tactical advantages not to be skipped over.”

When MR-GO was finally approved by Congress and signed into law by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in March 1956, F. Edward Hebert called it, “undeniably one of the most important pieces of legislation passed in the last decade.” Louisiana Representative Hale Boggs lauded it as, “A great day for New Orleans, Louisiana and the entire Mississippi Valley … the realization of a dream come true.”

While MR-GO’s alleged benefits for New Orleans, the upper Mississippi and national defense were highlighted, little was said about benefits to be gained by St. Bernard Parish where the greatest environmental impact would be felt. St. Bernard was mentioned at the ground breaking ceremonies in 1957 when F. Edward Hebert said that the canal, “will open new vistas for the parish of St. Bernard.” He assured his listeners that, “St. Bernard is a full partner in this great accomplishment. We have received full co-operation and understanding from the officials of the parish. Everything we have accomplished for New Orleans, we have designs to accomplish for St. Bernard.”

A Burden to St. Bernard Parish

During the next half-century MR-GO actually offered few benefits to St. Bernard. Soon after its completion in 1963 its erosion of the shoreline was evident and before long vast acres of wetlands were being destroyed. Erosion expanded the canal banks from 500 feet wide to some 1,500 feet wide. Saltwater intrusion from the Gulf killed vast stands of cypress trees. Crawfish and oyster beds were ruined, while the livelihoods and homes of commercial fisherman were washed away. Saltwater seeped into the Industrial Canal and into Lake Pontchartrain where it aggravated dead zones. Of greatest worry, MR-GO was blamed for eroding protective coastal wetlands and funneling the hurricane storm surge of Hurricane Betsy that flooded parts of St. Bernard and New Orleans in 1965 — more devastatingly the same thing happened 40 years later during Hurricane Katrina.

A headline in the Times-Picayune of July 28, 1990 about St. Bernard’s dilemma with MR-GO summed up the situation by saying — “Gulf Outlet is a Disaster ….” In the accompanying article it was argued that the parish had received no economic benefits, and its police jury was being forced to pay off a large loan it could not afford for a hurricane protection system needed to replace the natural wetland tidal barrier that MR-GO had washed away.

As MR-GO neared completion in 1963, the Times-Picayune in a series of articles reported on a significant problem. Even in 1943 the Dock Board and the Tidewater Canal Association, “were becoming increasingly doubtful of the adequacy of the Industrial Canal lock and more insistent on the need for a new and larger lock with greater depth over the sill.” In 1943 the lock was, “only fairly adequate,” but by 1963, “the free exchange of ships between ship channel and river is no longer possible.” In 1963 water in the lock was 31.5-feet deep; MR-GO was 36 feet deep; some ships required 34 feet — the southwest pass of the Mississippi was 40 feet deep at the time.

Without an adequate lock at the Industrial Canal, plans for construction of a huge new container port and industrial and distribution complex along the Intracoastal Waterway could not proceed as planned. In the 1970s the Corps of Engineers proposed to cut a canal with a 50-foot deep lock near Violet in St. Bernard Parish. This was dealt a blow when St. Bernard residents succeeded in defeating the plan, since they feared that it would cut the parish in half, as well as worsen problems already being created by the MR-GO.

A Funnel For Tidal Surges

The Corps have since moved its efforts back to the Industrial Canal where it began expanding the lock in 2002 prompting considerable opposition from the flanking neighborhoods of Bywater and Holy Cross. The work was stopped by 2007 when a federal district judge ruled that further environmental study was needed to determine the impact of dredging and the deposit of sediment required by the expansion.

Environmentally MR-GO is a creation in the 1950s — a time when the study of environmental impact scarcely existed. This has changed dramatically over half-a-century, and was summed up in 1976 by Robert Schroeder. He was head of the study for a proposed expansion of the Intracoastal Waterway, and noted an earlier 1962 study for the same proposal to the Times-Picayune remembering that environmentalists were never heard of in 1962 — but by 1976, “We have a whole environmental section now …. Back then I think we had one biologist.” The same would have been true for early MR-GO studies.

Although shoaling was not supposed to be a worry for MR-GO, it has been problematic from the start. On February 8, 1967 the New Orleans States-Item reported that by 1965 the canal’s depth had been reduced to 33 feet after which it took two years to dredge it down to its normal 36 foot depth. In spite of this work, shoaling continued and could not be stabalized. The States-Item said the situation, which was unexpected, was created by a combination of tides, winds and ship movements. Since then hundreds of millions of dollars has been spent trying to stabilize MR-GO. In 1998 Hurricane Georges swept so much silt into the canal that its depth was as shallow as 25 feet, forcing its closure for several months of dredging. Hurricane Katrina deposited enough silt in 2005 to reduce its depth and prohibited its use by larger ships.

The success of the Intracoastal Waterway was unquestionable. Its cargo load grew from 5 million tons in the 1940s to more than 100 million tons by the mid-1970s.

MR-GO has not been so successful, especially since the economics of maintaining it are so great. In 1982 the Times-Picayune conceded that it, “has not been a total flop [but] it clearly has been more a failure than a success.”As late as 1999 it was only averaging about two ships a day, and the canal’s cost of upkeep was so great that at the time it cost $10,000 per ship to operate.

By the 1980s the Dock Board was still maintaining its riverfront wharves and even rebuilding some of them, as less emphasis was being placed on building new facilities along MR-GO. Quoted in the Times-Picayune of January 19, 1999, Ron Brinson, then executive director of the Port of New Orleans, said that the MR-GO, “is not adequate for [the port’s] long term needs … we want to eliminate our dependence on the MR-GO.” Brinson added that the federal government “can close the MR-GO … if they want to, but if they do it before we have alternate port facilities available they’ll be putting 10,000 jobs and a very vibrant segment of the economy at risk.”

This may have been decided by Hurricane Katrina’s massive storm surge which was funneled into St. Bernard and New Orleans by MR-GO, prompting the Corps of Engineers to recommend that the canal be shut down. In anticipation of this probable closure, some businesses dependent on MR-GO have begun planning to move away from the Industrial Canal. Among them are Southern Scrap Metal and CG Railway, the latter which is relocating to deeper waters at Mobile. Bollinger Shipyards, which had some of its docks on the Industrial Canal smashed by Katrina, has to use MR-GO since the Industrial Canal lock is too shallow for its needs. Bollinger relocated to other Louisiana ports in 2008.

It can be argued that MR-GO has done more harm than good, and while it might have been well meant, it began to go bad from the start. It has devastated wetlands and helped reduce some neighborhoods to flooded ruins. Its pie-in-the-sky promises of economic benefits hardly materialized, and while some businesses have succeeded in profiting from it, they are being forced to leave in the wake of its possible closure.

Since ground was broken for MR-GO 50 years ago, the waterway has come almost full circle. Once the port of New Orleans was called too dependent on its river and needed a canal — with time the port’s continued use of MR-GO is being questioned. In the 1950s the idea was to dig a canal that would seem to just take care of itself. Instead MR-GO requires too much care, and if it were left alone it would silt up and naturally shut down returning

—–

John Magill recently retired as a historian for The Historic New Orleans Collection.