Latest

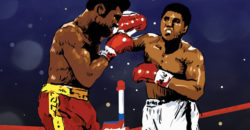

Muhammad Ali and the Early Days of the Superdome

Sherman Copelin on the politics of Ali's 1978 fight in New Orleans

Published: June 8, 2016

Last Updated: September 15, 2019

Illustration by Toan Nguyen

Sherman Copelin delivers this understatement in a wine bar on Magazine Street in Uptown New Orleans three days after Ali’s passing. The man who promoted the 1978 rematch between Ali and Leon Spinks at the Superdome remembers Ali as a friend. “Not only was Ali the greatest fighter in the world, he was the greatest humanitarians in the world. He was the most loving, forgiving, fun guy I ever met in my life.”

As the world mourns Ali this week, the Spinks fight registers small mention next to Ali’s great battles against Joe Frazier, George Foreman, and the federal government. But the bout was a significant moment in the contentious early years of the Superdome, and any history of the fight—and the many fights that surrounded it—begins with Copelin.

Copelin first met Ali during the 1960s as a member of the National Negro Business League, the commercial association founded by Booker T. Washington. Copelin went on to work for New Orleans Mayor Moon Landrieu, serving as one of several high-ranking African Americans in the city’s first fully integrated administration. He left City Hall in 1972, and in 1974 formed Superdome Services Inc. (SSI) with his associate Don Hubbard. The company quickly received the contract to manage the janitorial, ticketing, and security in the yet to be opened Superdome.

The stadium was mired in delays and under siege from state legislators who questioned the management of a project originally budgeted at $35 million that had spiraled toward $100 million. Landrieu sat on the state’s Superdome Commission. The awarding of a major contract to two black New Orleanians with little experience in event management, but ample ties to both Landrieu and Governor Edwin Edwards only amplified the outcry. Pitched to the legislature and voters in 1966 as a state project, the Superdome looked more and more like another New Orleans boondoggle. There was also a racial tone to the complaints. Landrieu’s efforts to integrate City Hall were unpopular in many parts of the state; granting millions of state tax dollars to promote black businesses didn’t win him many fans above I-10, the state’s traditional political dividing line. In 1970s Louisiana, the chasm between city and state widened as more African Americans gained political power in Orleans Parish. The Dome controversies were at the center of this conflict.

Then in January 1975 Copelin and Hubbard were named as unindicted co-conspirators in a case surrounding alleged bribes during Copelin’s time in the Landrieu administration. The charges put SSI, Landrieu and the Dome itself under siege in the months leading up to the August 9, 1975 opening of the stadium. Former Governor McKeithen, a major force behind the Dome’s conception, lamented, “There is no city on god’s green earth” where more people were “trying to make a fast buck.”

Problems during the first months of operations only stoked the furor. Attendees complained of lax security, overpriced beer, and the smoky air. A legislator’s nephew was mugged in a concession line, and the Allman Brothers band sued over unreported ticket sales. Landrieu pleaded for patience: “General Motors didn’t start overnight.” Copelin saw the complaints as racially motivated. “[U]nfortunately those interest have used race as one of the basic innuendos,” he told The Times-Picayune, “playing on the prejudice that because SSI is predominantly black, it is shiftless and incompetent.”

And then all hell broke loose. Granted immunity in the bribery case, in November 1975 Copelin admitted to accepting money.

At a November 17, 1975 commission meeting, Landrieu’s eyes welled with tears. “The staff of this commission has worked as hard as any staff has worked,” he said. “You can’t run this building in the newspapers…” The previous morning, in a front page editorial titled “Dome: Clean House Now!” The Times-Picayune declared, “The case against Messrs. Copelin and Hubbard is already open and shut.” Edwards called for a change in management.

“I think we have as fine a staff as any that could be assembled,” Landrieu told the commission, “but the people are not going to let it rest until Sherman Copelin resigns.”

Copelin and Hubbard refused to resign, and accused the state of offering to pay them off. The battle lasted two more years, culminating when the state terminated SSI’s contracts and evicted the company from the Superdome in November 1977.

So how did the same two men end up promoting a heavyweight title fight in the same building just 10 months later?

“We never would’ve gotten the fight if Ali didn’t say, ‘I’m going to fight in the Superdome for this guy,’” says Copelin.

Armed with his friendship with the fighter, Copelin approached promoter Bob Arum about purchasing the rights to the fight. Arum had failed to secure his preferred location, Johannesburg, South Africa, but remained wary of New Orleans. “He didn’t give us but 72 hours to come up with $3 million,” says Copelin. “He didn’t want us to have it.” Once the sum was secured and the date set for September 15, 1978, Copelin and Hubbard engaged with the new management at the Superdome. “We were just another tenant in the building. We did the same thing that anyone else would.”

“I said, ‘Look, we know more about this building than anyone else. We can get this done.’”

According to Copelin, there was no resistance at the state level. In fact, he received an assist from the legislature in a battle against the state boxing commission, which demanded a cut of all ticket sales.

“The math didn’t work. They were getting 30% or something. We wouldn’t do the fight. There were a lot of backroom procedures and adjustments that had to be made to do the fight. But it all worked out good for Louisiana, good for my group, good for Ali.”

Governor Edwards, who Copelin calls “like a brother,” also helped out. According to a Sports Illustrated piece published after the fight, the governor convinced the legislature to lower the state’s special sales tax from 5% to a maximum of $5,000; ticket revenue was reported to be $5 million, making it quite a discount. Copelin still had pull in Baton Rouge.

The bout was billed as “The September to Remember.” The most powerful influence on revenue, Copelin says, was Ali.

“Ali was scheduled to do this [Motocraft] battery commercial, which became a big hit in those days. He was going to Alaska. I had a good relationship with him, so I didn’t have to call any handlers. I call him and said, ‘Man, I need you to come down and hype my tickets again.’ So he told his staff that he was going down to New Orleans. He said, ‘Man, the brother wants me to come down there.’ Bam, the tickets sold.”

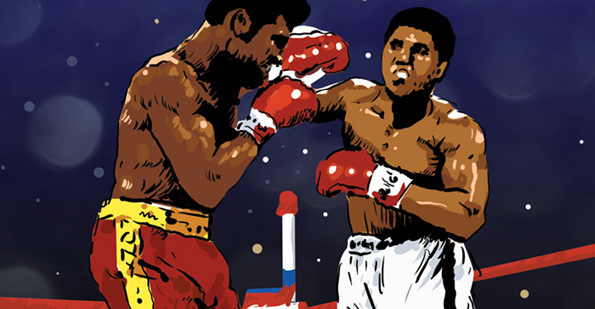

The fight survives on YouTube. Even viewed on an iPad, the crowd looks immense under the dimmed Dome lights. Howard Cosell describes “the crush of the crowd” that presses against each fighter’s path to the ring. Spinks wears a cowboy hat; his two front teeth are missing. A phalanx of state troopers surrounds Ali, who struggles to reach the ring to the sounds of a lone clarinet playing “When the Saints.”

“He is the storyline, and he has been the storyline his whole life,” says Cosell, who continues to marvel at the size and roar of the audience. “Twenty-five years in sports, I have never heard a crowd like this. Never!”

Ali’s rival, former heavyweight champion Joe Frazier sings the national anthem. After the third round, a reporter interviews Sylvester Stallone, who calls it “a mathematically precise fight.” It would be the final victory of Ali’s career, a 15-round split-decision.

Copelin had a ringside seat that he occupied for no more than five minutes in the 15-round fight. “I was doing everything from playing security to playing usher to playing janitor to whatever it took to have a successful event, and did not see much of the fight.”

Just as contentious as the events inside the ring were the business dealings surrounding the fight. Copelin and Hubbard were joined by two other principal investors, businessman Jake DiMaggio and New Orleans City Councilman Philip Ciaccio. Today it’s hard to imagine a sitting councilman promoting a boxing match, especially with such controversial partners. The partnership hit the rocks, however, just days before the fight when Ciaccio, DiMaggio and Arum accused Copelin, Hubbard, and Arum’s employee, Butch Lewis of skimming money by accepting bogus finders fees. Copelin and Hubbard filed their own suit against Arum for labeling them “hooligans.” According to Copelin, the roots of the dispute lay with Arum and DiMaggio.

“Bob Arum was a prosecutor and he investigated boxing. When he found out how much money there was, he resigned and became the biggest boxing promoter in town.” He praises the late Lewis as a true advocate for boxers.

“Here’s what happened. I had to raise $3 million. I raised the $3 million. But during the process, Jake DiMaggio represented that he had certain resources he didn’t have. So when I found out he was phony, I didn’t overreact or kick him out. But when it came time to be responsible to the investors, by the formula we had, if you don’t put up nothing, you can’t expect to get something. It was Jake DiMaggio who went to the feds and made up all these allegations. Nobody who put up money had a problem.”

That appeared to be the case. By Sunday, two days after the fight, the suits were settled and the partners agreed to part ways amicably. Everyone seemed satisfied. Except Ali.

At a press conference on Monday, the Greatest let fly.

The problem, according to Ali, was that whites didn’t like the fact that “[racial expletive] are counting $6 million.”

“I’m going to tell it throughout the world. I’m going to make a world tour and if I hear any more trouble about these men being sued, I’m going to see President Carter in three more days. He called me after the fight. I’m going to Carter and I’m sure tell it all. I’m going to shout it on the rooftop of the world, trying to discredit these black men so they can’t promote no more…”

Copelin and Hubbard, along with Joe Frazier and comedian Dick Gregory, listened as Ali continued.

“Can you believe these two black men showed the world they can do business like any other men? These former slaves, Negroes, united with trainers and managers who happen to be black?”

The comments seemed to echo the SSI dispute.

“Ali knew what the deal was,” says Copelin.

He called upon his friend for help again in 1982 during his run for the District E City Council seat. Ali spent a day canvassing New Orleans East to no avail: Copelin lost. Copelin maintained his close connections with Edwards, eventually winning a seat in the Louisiana House of Representatives and serving as Speaker Pro Tempore. During the 1983 gubernatorial campaign, Copelin asked Ali for another favor.

“I got him back in the campaign for Edwards. I had a system set up. I had some of the first computers, and you’d be able to say, ‘If you vote at precinct A, Ali will be there to say hello and sign autographs.’ And he did show up.’”

It’s doubtful anyone still possesses a recording of Muhammad Ali performing a robocall for Edwin Edwards. Copelin lost most of his memorabilia from the fight to Katrina. He last spoke to Ali a year ago.

“We were friends, man. To me, Ali was just another friend. I understand he was a very high profile, famous guy, but to me he was just like another brother.”