Mystery at the Museum

Exciting discoveries in the archives

Published: June 1, 2020

Last Updated: September 1, 2020

Photo by Emily Feazel

The medieval book of hours.

All museums have their share of mysteries: the painting relegated to the storerooms as “the school of” that turns out to be an original Rembrandt, the “lost” copy of the Declaration of Independence that turns up during an inventory of the museum’s library archives, and various other “oops” with happy endings. But I have to admit I wasn’t expecting one of those as I began working my way through the Norton’s storerooms.

The museum had recently added a new wing and, as a result, a number of items needed to be inventoried and re-organized in the new space. I was enjoying sorting through this Aladdin’s cave. Most of it was ephemera: a folded US road map from 1837, a dance card from a Gilded Age debutante’s ball, a collection of National Geographic. In a glass-front cabinet, I spotted a cedar cigar box. I was enchanted by the box itself, but when I pulled it from the cabinet, its weight indicated that it contained something. I opened it, launching one of the most remarkable experiences of my life.

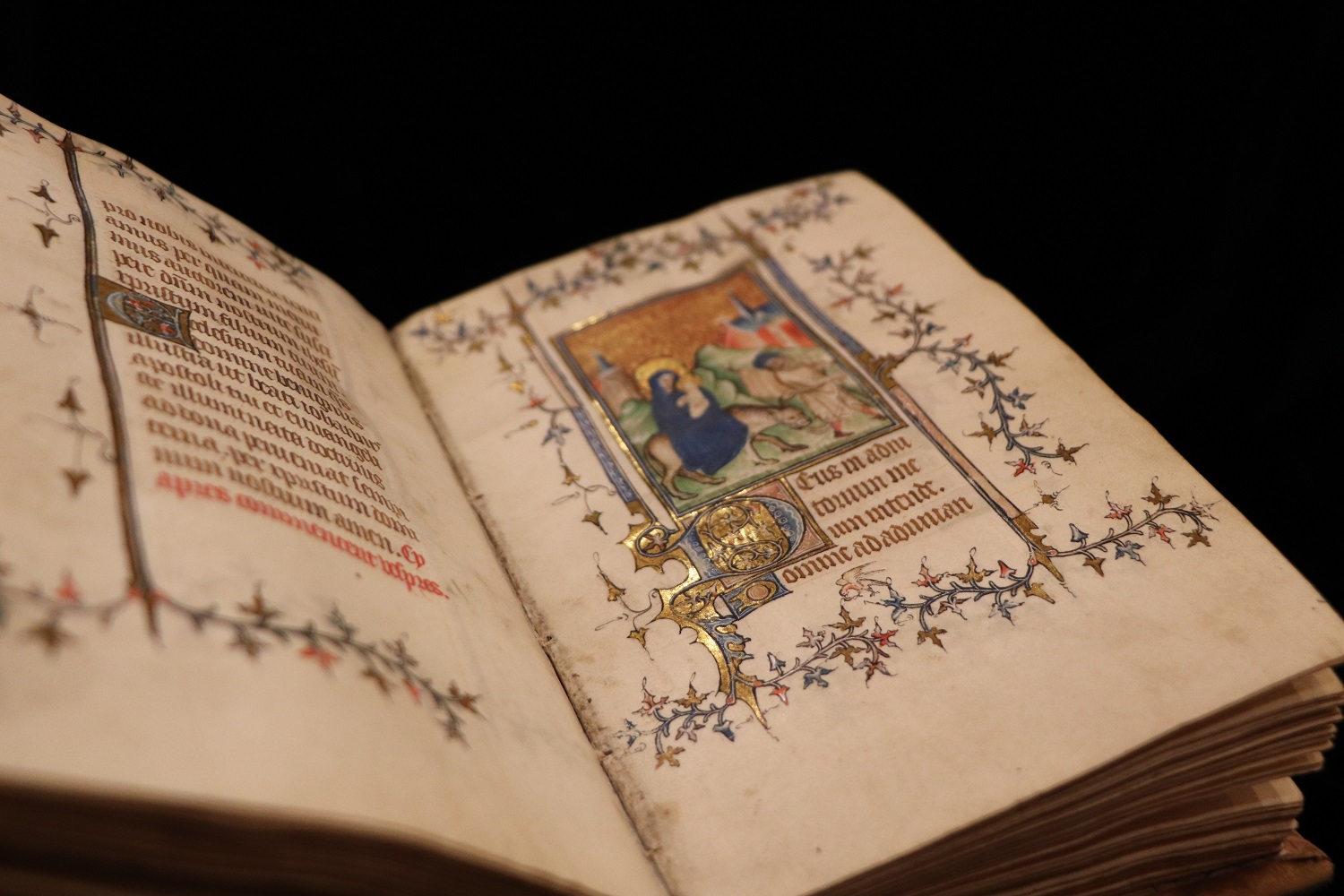

It was a book with a worn velvet cover. The pages were vellum and the calligraphy clearly hand-written. As I turned the pages, I found beautiful religious-themed miniatures—only an inch and a half by an inch in size, with incredibly careful delineation and detail. Their color was still jewel-bright. It looked like a medieval book of hours. I couldn’t believe I was holding such a remarkable find.

My boss and I quickly approached Jerry Bloomer, the Norton’s longtime registrar. Jerry searched his memory, then the files, and emerged with the bill of sale for a book of hours purchased by the Nortons from an M. Gottschalk in New York in 1939, listed as originally from the library of John Hall Parlby. We were further titillated by a long inscription in French on the back leaf of the book that apparently dated from the fifteenth century.

I contacted Dr. Kay Sutton of Christie’s London manuscript division to do an appraisal. Sutton came with an entire complement of Christie’s professionals, offering to take a look at our rare book collection as well as the book of hours. When her report came a month or so later, we were elated. Our book of hours was French in origin, produced in Paris sometime around 1390. In addition, we had a portrait of the man who had originally commissioned the manuscript, found in the miniature on leaf 127, where he is shown kneeling before the Virgin and Child (his identity remains unknown). In the fifteenth century, the book had passed into the hands of Thomas Eberhardus, rector of the Sorbonne, and devotions in French were added. In the seventeenth century, it passed to a congregation of Benedictines, and then made its way to Reverend Samuel Parlby of Stoke in Suffolk in Great Britain. His descendant sold it through Sotheby’s, thence to M. Gottschalk, and from there it found its way to us.

Because the illuminations were painted with what are known as fugitive dyes that fade very quickly when exposed to light, we can’t put this happy storeroom surprise on display year-round, saving it for a brief appearance during the Christmas holidays. In between its visits to the outside world, the manuscript resides in our safe, securely nestled in a cedar cigar box.