Spring 2017

A New Orleans Griot Returns to Print

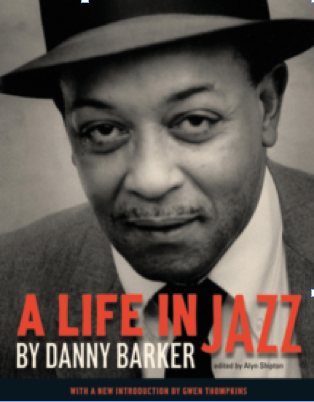

The Historic New Orleans Collection publishes new edition of Danny Barker’s autobiography

Published: March 1, 2017

Last Updated: October 5, 2018

Storyteller, researcher, songwriter, performer, and mentor Danny Barker (1909–1994) was an elder statesman of jazz, appearing on more than a thousand recordings and penning dozens of original songs. A Life in Jazz, first published in 1986, represents decades of work Barker undertook to write the intertwined stories of his life and music. The Historic New Orleans Collection’s new illustrated edition of his autobiography brings his story back into print, accompanied by more than one hundred images. Gwen Thompkins, host of public radio’s Music Inside Out, reflects on Barker’s legacy in her introduction, and the complete discography and song catalog showcase the breadth of Barker’s work. Through his struggles, triumphs, escapades, and musings, A Life in Jazz reflects the freedom, complexity, and beauty of this thoroughly American black music tradition. The following is an excerpt adapted from Chapter 15, “Jelly Roll Morton in New York.” — Molly Reid

When I arrived in New York City in 1930 my uncle Paul Barbarin and my friend Henry “Red” Allen took me to the Rhythm Club, which was known for its famous jam sessions and cutting contests. The afternoon I walked into the Rhythm Club, the corner and street were crowded with musicians with their instruments and horns. I was introduced, and shook hands with a lot of fellows on the outside. Then we entered the inside, which was crowded. What I saw and heard I will never forget. A wild cutting contest was in progress, and sitting and standing around the piano were twenty or thirty musicians, all with their instruments out waiting for a signal to play choruses of Gershwin’s “Liza.”

I was watching the jam session with interest when Paul said, “Come over here and meet Jelly Roll and King Oliver.” Paul led me through the crowd to where King and Jelly stood. I had noticed Fletcher Henderson was playing pool and seemed unconcerned about who was playing in the jam session, or who was there. Whenever I saw him at the club he was always playing pool seriously, never saying anything to anyone, just watching his opponent’s shots and solemnly keeping score. All the other musicians watched the game and whispered comments, because he was the world’s greatest bandleader. Paul told King and Jelly, “Here’s my nephew; he just came from New Orleans.”

King Oliver said, “How you doing, Gizzard Mouf?” I laughed, and Jelly said, “How you Home Town?”

I said, “Fine.” And from then on he always called me “Home Town.” Jelly, who was a fine pool and billiard player, had been watching and commenting to Oliver on Fletcher’s pool shots. King could play a fair game also. Jelly said (and he didn’t whisper), “That Fletcher plays pool just like he plays piano—ass backwards, just like acrawfish.” And Oliver laughed and laughed until he started coughing.

Jelly was constantly preaching that if he could get a band to rehearse his music and listen to him, he could keep a band working. He would get one-nighters out of town, and would have to beg musicians to work with him. I learned later that they were angry with him, because he was always boasting about how great New Orleans musicians were. Jelly’s songs and arrangements had a deep feeling lots of musicians could not feel and improvise on, so they would not work with Jelly—just could not grasp the roots, soul, feeling. At that time most working musicians were arrangement-conscious, following the pattern of Henderson, Redman, Carter and Chick Webb. Jelly’s music was considered corny and dated. I played quite a few of these one-nighters with Jelly, and on one of the dates I learned that Jelly could back up most of the things he boasted of.

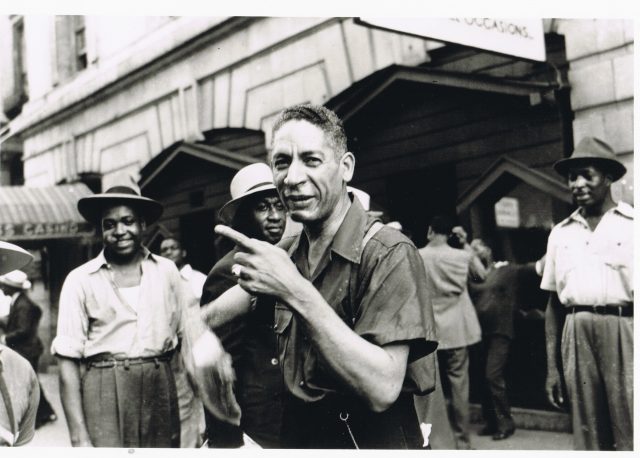

Jelly Roll Morton outside of the Rhythm Club in New York, ca. 1939. Courtesy of the Danny Barker Collection, photo by Danny Barker.

On one date the band met at the Rhythm Club about three in the afternoon and left from there in Jelly Roll’s two Lincoln cars to play in Hightstown, New Jersey, at a playground that booked all the famous bands at that time. On the way we came upon a scene of much excitement. A farmer in a jalopy had driven off a country road right in the path of a speeding trailer truck. The big truck pushed the jalopy about a hundred feet, right into a diner. The impact turned the diner over, and the hot coffee percolator scalded the waitresses and customers. Nobody was badly hurt, but they were shocked and scared and screaming and yelling.

A Life in Jazz by Danny Barker

Edited by Alyn Shipton,

with a new introduction by Gwen Thompkins

Published by The Historic New Orleans Collection

Hardcover • 254 pp. • 8″ x 10″

115 color and b/w images • $39.95;

available now at The Shop at The Collection

or online retailer

We pulled up and rushed out to help the victims, who were frantic. Jelly yelled loudly and calmed the folks down. He took complete charge of the situation. Jelly crawled into the overturned diner and called the state police and hospitals. They sent help in a very short time. Then he consoled the farmer, who was jammed in his jalopy and couldn’t be pulled out. His jalopy was crushed like an accordion against the diner by the big trailer. The farmer was so scared he couldn’t talk, and when the emergency wrecker finally pulled his jalopy free and opened the door and lifted him out, I noticed that he was barefooted. Jelly told me that happens in a wreck; the concussion and force cause a person’s nerves to constrict and their shoes jump off.

We passed some men who were hunting in a field. They were shooting at some game that were flying overhead. Jelly said, “Them bums can’t shoot. When I was with Wild West shows I could shoot with the best marksmen and sharpshooters in the world.” Either Benford or Pinkett said, “Why don’t you stop all that bullshit?” And that argument went on and on.

When we arrived at Hightstown and drove into the entrance of the playground and got out of the cars, I noticed a shooting gallery. So I said to Jelly, “Say, Jelly, there’s a shooting gallery.” Jelly’s eyes lit up and he hollered, “Come here all you cockroaches! I’m going to give you a shooting exhibition!” We all gathered around the shooting gallery and Jelly told the owner, “Rube, load up all of your guns!” And the man did. Jelly then shot all the targets down and did not miss any. The man set them up again and Jelly repeated his performance again. Then he said, “Now, cockroaches, can I shoot?” Everybody applauded. Jelly gave me the prizes, as the man shook his hand. Then he and Jelly talked about great marksmen of the past, as his hecklers looked on with respect.