Sound Advice

The New Orleans Pop Festival

Fifty years since Louisiana’s Woodstock

Published: May 31, 2019

Last Updated: August 30, 2019

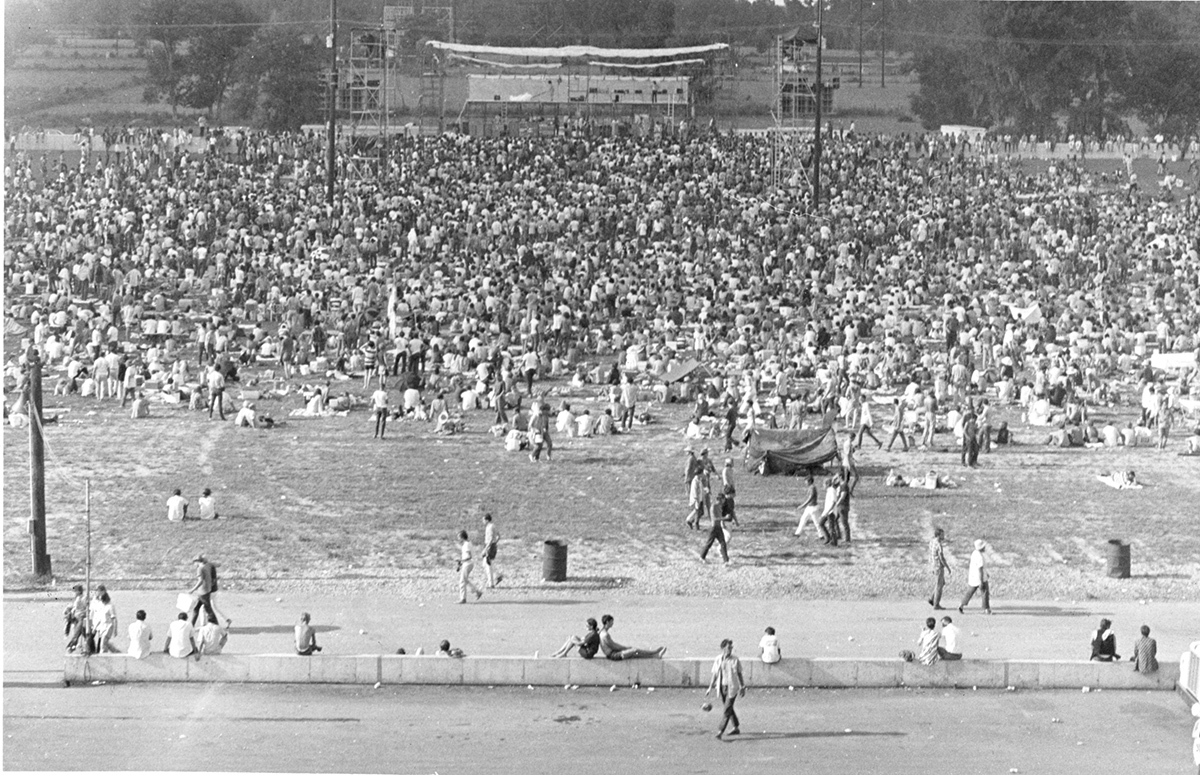

Photo by Sam King / Baton Rouge Advocate

The New Orleans Pop Festival (which took place in Prairieville) followed Woodstock by two weeks, attracting many of the same acts.

The New Orleans Pop Festival took place not actually in New Orleans but in Prairieville, Louisiana, about a twenty-minute drive south of Baton Rouge, on the grounds of the Baton Rouge International Speedway. Several of its marquee acts had been onstage at the “Aquarian Exposition” on Max Yasgur’s dairy farm in Bethel, New York, two weeks before; others, like Joplin, Canned Heat, and the Chicago Transit Authority had been down south earlier that summer, too, playing the Atlanta International Pop Festival over the Fourth of July weekend. Local attractions like Deacon John, Dr. John, Potliquor, and Doug Kershaw were also on the Prairieville bill.

Sixties festival culture was at a peak that Woodstock summer. The previous decade had lain groundwork with impresario George Wein’s establishment of the Newport Jazz Festival in 1954—memorably referenced in the Louis Armstrong film High Societyand Newport Folk in ’59. It had come into full, heady, psychedelic blossom in 1967, with a summer-of-love twofer that June: the Fantasy Fair and Magic Mountain Music Festival in California’s Marin County and the more widely heralded Monterey Pop Festival, both of which showcased that state’s wealth of cosmically groovy rock and folk alongside international acts like The Who and soul stars like Otis Redding and Booker T. and the M.G.’s.

The trend picked up over the next year or so, certainly spurred on at least a little bit by D. A. Pennebaker’s masterful Monterey Pop concert film, which came out at the end of 1968 (and was playing in New Orleans theaters in June of ’69, just in time to hype up fans for the Prairieville fest). Denver, Seattle, Atlanta, Dallas, and Toronto, among others, hosted multi-day rock festivals that year, offering fans what would become enshrined in consciousness as the Woodstock experience: temporary communities of like-minded people, centered around sounds that reflected their groovy ideals back at them in a rose-colored haze of dope and dancing and fuzzy guitars.

Pop Fest co-producer Steve Kapelow, a New Orleans native in his mid-20s, had worked on the first Atlanta Pop Festival. His career in festival promotion would unfortunately be short-lived, due to the vagaries of the business. He invested more than a quarter of a million dollars in the second Atlanta Pop Festival in 1970, but—as at Woodstock—fans overwhelmed the gates, forcing organizers to resort to opening them up for free. By 1971, the year of his planned week-long Celebration of Life music festival, local authorities had grown so suspicious of such events—they’d read about throngs of hippies descending on sleepy towns to do free love in mud puddles, or whatever—that he found his production booted from several planned sites. When he finally secured a soybean farm on the banks of the Atchafalaya River in McCrea, Louisiana, there was little time to prepare; bands cancelled, infrastructure was slipshod, and the ambitious event snowballed into calamity, culminating in the death of at least three fans.

But two weeks after Woodstock, the festival landscape was still as bright as a tab of orange sunshine. Mainstream press wrote approvingly about the party in Prairieville. “New Orleans Pop Festival Makes Many People Happy,” observed the Associated Press report from Tuesday, September 2, 1969, noting that area merchants had been “astonished” at attendees’ “unexpected good behavior.” The Times-Picayune’s reporters called the fans “young, patient and glad to be there,” even characterizing the miles of standstill traffic on Airline Highway as pleasant enough: “They opened car doors, sat on hoods and trunks and smiled.” And a critic from the Hattiesburg American newspaper rhapsodized about the music, writing, “I have never enjoyed a weekend more than this one . . . I expected it to be good. It was more than good; in some instances, it was brilliant.”

There were plenty of “toilets, concessions and water,” the Times-Picayune declared happily, for the thirty-thousand-odd attendees estimated by area police, paying thirteen dollars a head for a two-day pass. It had been a success, by all accounts—except, apparently, for one: the alternative press.

Here’s our story’s entertaining coda. NOLA Express, the bimonthly counterculture magazine, had run a glowing review of the Atlanta Pop Festival earlier that summer. But instead of following it up by previewing the upcoming effort closer to home, editors chose instead to devote a full page to chronicling an argument with Kapelow. Publisher Darlene Fife had phoned him, she wrote, asking if he wanted to buy an ad for his next festival. He did not, she reported, because of a letter to the editor they’d run in the issue of the Atlanta festival review, from a reader opining that the Prairieville site “ain’t worth a good hardy sh–.” Kapelow thought she should have called him for a rebuttal before running the letter; Fife offered him the chance to respond in the forthcoming issue; Kapelow responded, she wrote, “that the damage was already done and anyway no one read NOLA Express.”

The airing of media dirty laundry continued with a testimonial from the Express’s ad salesperson that he had himself offered Kapelow a back-cover advertisement—but that Kapelow had declined, saying he didn’t have copy ready in time. Based on his knowledge of local deadlines and the timing of a Pop Fest ad appearing subsequently in the Times-Picayune, the ad rep wrote, “In my opinion, Mr. Kapelow is a liar.”

The writers took a few jabs at Kapelow, the son of a prominent New Orleans real estate developer, for making money off the counterculture (“We shall see if he distributes all the profits to the hip community of New Orleans,” Fife wrote) before announcing that they would go ahead and run a full-page ad for the festival “for the people of New Orleans, because we dig music and free love in quiet and peace. This ad is paid for by the editors and readers of NOLA Express and not by Mr. Kapelow.”

But they didn’t spend any more ink on New Orleans Pop’s bands or other attractions. Instead, the festival-week issue featured a cartoon map to the site on the cover, with barbed fencing superimposed—and a how-to feature inside explaining how to cut through fence wire.

Alison Fensterstock has written about American arts and culture for NPR, Pitchfork, Rolling Stone, the New York Times, and others. She has served as the music critic for both Gambit and the Times-Picayune in New Orleans.