Passed By

Louisiana off the Interstate

Published: June 1, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Story and photos by Christie Matherne Hall

The remnants of the bridge to East Orange.

—John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley: In Search of America

The United States Interstate Highway System is an engineering marvel. Comprising nearly fifty thousand miles of limited-access, high-speed concrete, the system provides efficient connections to places previously only accessible by back roads. Born of President Dwight Eisenhower’s dream to create a controlled-access American autobahn for public and military use, the interstate highway system has left its mark nationwide in a path of progress. “It is not an exaggeration,” read the 1996 “40 Years of the US Interstate Highway System” report for the American Highway Users Alliance, “that the interstate highway system is an engine that has driven 40 years of unprecedented prosperity and positioned the United States to remain the world’s pre-eminent power into the 21st century.”

President Eisenhower signed the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956, and the United States spent $114 billion building it over the next half century. But building these new highways wouldn’t be as easy as signing a check. Interstate proponents promised efficiency, interconnectivity, and improved economies due to the new highways; but interstate construction required land, which often had forests, homes, or entire neighborhoods occupying it. Because of this give-and-take, the road to building interstates in the United States was an intensely political process, requiring a litany of negotiation. And in those negotiations, there were losers.

Some towns grew into bigger cities when an interstate went through them, which generally improved economies and access to services; but they often created traffic problems—as I-10 did to Lafayette and Baton Rouge, for example. Interstates also bisected or destroyed historic neighborhoods in bigger cities, such as the predominantly African American Valley Park community in Baton Rouge, which lost four hundred homes to I-10 and cut off the pedestrian route used by neighborhood children to get to school. Meanwhile, a drive on the former main route from north to south, US Highway 71, reveals a roster of pre-interstate towns that were not close enough to the new I-49 for it to benefit them—just close enough for it to significantly reroute through-traffic. Bunkie, Cloutierville, Powhatan, and Montgomery are only a few of the many towns affected by I-49 along the now lonely US-71.

The Playground of Orange, Texas: East Orange, Louisiana

Harry Choates biographer Andrew Brown wrote, “If the music scene in east Texas and southwest Louisiana had a nerve center in the 1940s, it was East Orange.” East Orange, Louisiana, existed right across the Sabine River from Orange, Texas, about ten miles southwest of Vinton, Louisiana. This remote strip of dance halls, restaurants, bars, and casinos along US 90 was a mecca for traveling musicians and a frequent vice-filled getaway for inhabitants of Orange; it was a place where folks could spend their evenings cockfighting, drinking, gambling, and perhaps enjoying illegal company, “in defiance of sanctimonious Baptist condescension in Orange, Texas,” wrote Ted Olson in his book Crossroads: A Southern Culture Annual.

Journalist Mike Louviere wrote in the Orange Leader in September 2018 that East Orange was far enough away from Lake Charles law enforcement—and out of Texas police jurisdiction—that “Louisiana authorities often turned a blind eye to happenings in East Orange.” This allowed dubious business and patron activities—some of which were illegal in Texas—to go on uninterrupted. At least one East Orange casino—the Showboat—was known for discouraging the exits of gamblers who won big. Louviere wrote that “reportedly, those who operated the Showboat did not take kindly to those who tried to leave as winners from their night of gaming. It was a rough and tough place, there were fights, reports of people being ‘knocked in the head,’ and occasionally a body found floating in the water around the boat.” In February 2015, Louviere noted in The Record Live, that “when the water was clear at low tide you could see numerous billfolds laying on the bottom as you crossed the gangway to the ship. Even though they had no authority, Orange police would often go to the area and try to help with identification of bodies.”

Orange entered an enormous population boom during World War II, thanks to the US Navy’s new shipbuilding facility, and even more people found their way across the Sabine River to the East Orange playground. But when US 90 was re-routed after the war, and a new Sabine River bridge was built a few miles north of the old route’s swing bridge, the businesses in East Orange suffered. It was simply less convenient to get there. Finally, the old swing bridge was removed in the early 1960s, which spelled the end of East Orange. Some clubs relocated to the rerouted US 90, and several new nightlife spots popped up there in a revival of sorts.

At this point, a traveler could still drive to the old East Orange, but not for long. Local arsonists burned the wooden bridge that stretched across the marsh on the old US 90—called the One Mile Bridge—in 1973. Louviere suggested that there may have been no effort to extinguish the fire because it was in such a remote area. Those looking for remnants of East Orange must do so by boat today—which isn’t difficult, considering the area is now a well-maintained Calcasieu Parish boat launch.

Bonnie and Clyde’s Last Drive: Highway 154 by way of US 80

US Highway 80 connects the northwestern border of Louisiana near Shreveport to the northeastern border at the Mississippi River. It runs a wobbling parallel to I-20, which was completed in Louisiana circa 1960. Besides the cities of Shreveport and Monroe, and the college towns of Ruston and Grambling, the towns along US 80 are mostly small rural enclaves.

A drive down US 80 was once a tour of the lively downtown areas of these small towns, where travelers would stop for fuel and food. Towns like Ada, Gibsland, Arcadia, and Choudrant ended up a slight distance away from I-20 onramps after the highway’s completion, and the new route was faster and more convenient for travelers than US 80. Like many old thoroughfares roughly traced by newer interstate highways, US 80 still exists, but with far less traffic than before. These towns and others like it along US 80 have suffered from population decline since 1980, due to the construction of I-20, loss of industry, or a combination of factors. In an effort to lure more through-traffic, some towns along US 80 have struck the dinner bell of tourist attractions; Gibsland and Arcadia lay claim to a slice of high-profile criminal history.

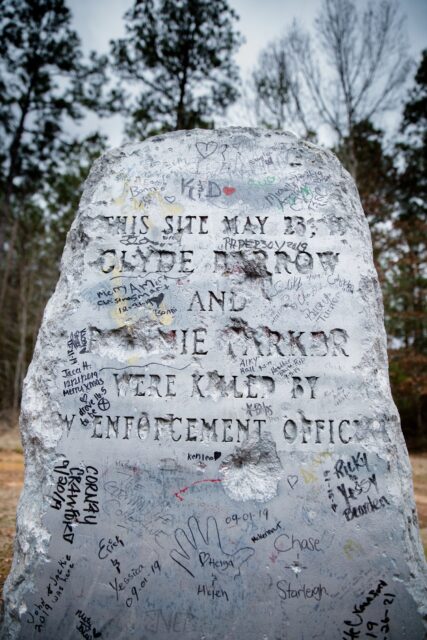

One of the most notable buildings in Gibsland is the Bonnie & Clyde Ambush Museum. It’s notable because you can’t miss the word “AMBUSH” in large font, right above the entrance and in the middle of the tiny downtown strip. The infamous lover-criminals Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow ate their last meal on earth in that building, formerly Ma Canfield’s Café, right off US 80 on Highway 154. On May 23, 1934, they stopped at the café and ordered some sandwiches to take with them. Rolling south on Highway 154, the pair was headed to a rumored hideout in nearby Sailes, Louisiana. About a mile and a half from Sailes, they stopped to meet a fellow criminal’s father, who appeared to have a busted tire on Highway 154. A crew of six police officers from Texas and Louisiana, all of whom had been camping out in the woods overnight waiting for Bonnie and Clyde to drive by in their Ford Deluxe, jumped out of the bushes and fired over a hundred bullets at the two criminals before they even got out of the car. Bonnie Parker died with a half-eaten sandwich still in her hands.

The Ford Deluxe, bodies inside, was towed to a funeral home that doubled as a furniture store. Eventually, over ten thousand people turned up in Arcadia, which had a population of about seven hundred at the time. As the embalmers did their work, a crowd of onlookers gathered in the furniture showroom in hopes of getting a glimpse of the bodies, or perhaps a souvenir to take home. The store owner’s wife, Inez Conger, reportedly resorted to dumping formaldehyde on the crowd because they were standing on showroom furniture and ruining the merchandise.

The town of Gibsland pays homage to the infamous criminals every May, on the weekend closest to the 23rd, with the Authentic Bonnie & Clyde Festival, which hosts re-enactments, a lookalike contest, bingo, and a gathering for historians. Arcadia also banks on Bonnie and Clyde with its Bonnie and Clyde Trade Days, held every month on the weekend before the third Monday, featuring a revolving cast of vendors, adoptable puppies, plants, and sometimes, a petting zoo.

The Monster on North Claiborne Avenue: I-10 through the Tremé

In New Orleans, where Bayou Road crosses North Claiborne Avenue and turns into Governor Nicholls Street, an elevated segment of I-10 passes overhead. The gray pillars and vast expanses of parking lots under the interstate would be ugly, if not for the colorful scenes painted on the pylons. For those drawn to stop and look, there’s ample parking to do so. The scenes depict musicians, black business owners, and children playing outside of homes and picnicking on a neutral ground shaded by oak trees. The outer pylons feature painted oak tree after painted oak tree for at least a few blocks. These paintings depict what existed here before this two-mile stretch of I-10 was built.

In 1968, two elevated segments of interstate were on the docket to be built in New Orleans. One, the Riverfront Expressway, was to be built through the French Quarter and ultimately would separate the Quarter from the Mississippi River. A huge and well-documented community effort to preserve the historic Vieux Carré ultimately prevailed, and the Riverfront Expressway was not built. (Because of the rarity of this victory in the face of federally funded interstate plans, two of the main preservationists who fought to save the French Quarter wrote a book about it, called The Second Battle of New Orleans.)

The other stretch of interstate on the docket was to go straight through the historic Tremé neighborhood, a place of special significance to the black community in New Orleans. Due to segregation laws in effect until the 1950s, there were many “whites only” areas of the city, and Claiborne Avenue became a black community center, both in commerce and daily family life. Claiborne Avenue’s neutral ground—or median—looked more akin to a long forest. It was wide enough to be a gathering place, where kids could play ball and families had room for a good cookout, shaded by any of the hundreds of oak trees that lined both sides. At the time, the North Claiborne neutral ground was home to the longest line of oak trees in the country.

The state’s plan for the North Claiborne stretch of I-10 required the acquisition of 150 pieces of property within a stretch of less than two miles along the avenue. Naturally, the surrounding community was opposed, but the state prevailed. “We were basically told, this was just about a done deal,” Tremé resident and activist Norman Smith said on a video produced by the Congress for the New Urbanism (CNU). “Most of the people that I knew felt like, that’s that.”

The clearing of land began in 1966. Some two hundred oak trees were cut down or uprooted from the neutral ground, and five hundred homes and businesses in the area were demolished to make room for the two-mile stretch of interstate. Construction was completed in December 1972. After that, the fabric of the community slowly disintegrated. Many people were displaced and left the area. “You lost friends, you lost relatives, you lost,” CEO of Neighborhood Development Foundation and Seventh Ward native Fred Johnson said on the CNU video, “because people got displaced.”

It’s unlikely that removing the overpass is an option due to cost, but there have been recent efforts to revitalize North Claiborne, starting with a lease of the underpass area from Orleans Avenue to Esplanade. The plan is to transform it into retail space for up to sixty businesses of different types along with public art and green spaces. Nothing can replace the community that was uprooted over fifty years ago, but it’s a start.

I-49 South, US 90, and Bayou Teche

Along with a pride for their ancestral foodways, people who reside south of I-10 have another thing in common: They have no interstate connecting them. Instead, coastal Louisianans have US 90, which follows I-10 eastward from the Texas border and lurches southeast at Lafayette. From Lafayette, US 90 cuts through Broussard, Morgan City, Des Allemands, Boutte, Houma, Thibodaux, and Avondale before intersecting with I-10 in New Orleans.

Long before US 90 was the widened expanse it is today, it carved the less efficient route of LA 182. It wound along the Bayou Teche on a road first called the Old Spanish Trail—a coast-to-coast route completed in the 1920s. For many decades, US 90 went through New Iberia, Jeanerette, Charenton, and Franklin before the highway was rerouted away from the snaking Bayou Teche in the 1950s. Near the intersection of LA 182 and present-day US 90 is the town of Ricohoc.

Kaitlin Deslatte, a Michigan police officer and a native of Centerville, Louisiana, has roots along LA 182. Her grandmother, June Savoy Hebert, grew up in Ricohoc in the 1930s. Deslatte recalled her grandmother’s stories about watching the Greyhound buses zoom by on the old highway—the busiest road around at the time—curious about their destinations.

Steamboats with wealthy passengers traveled up the Bayou Teche, which was in Hebert’s backyard. When they heard the boat whistle, Hebert and her four siblings would drop what they were doing to get to the banks of the Teche. “Similar to Mardi Gras parades today, [the kids] ran along the edge of the water—hopping, waving, and asking for treats,” Deslatte said. “The captain and passengers threw large peppermint stick candies, so big that if only one of them caught one stick, they would chip it into small pieces to share.”

Deslatte said that when she was older, Hebert would take those zooming Greyhound buses to Franklin with her cousins to attend dances at the Blue Moon dance hall, often charming young men who owned cars to catch a ride back to Ricohoc. “The guys all waited at the bus depot for the ‘pretty Ricohoc girls’ to arrive,” Deslatte said, adding that June met her future husband, Nolan Hebert, at the Blue Moon after World War II.

During the 1950s, US 90 was rerouted to a less winding, more efficient route south of Bayou Teche. The Greyhound buses suddenly had a faster route, and no longer zipped by Hebert’s home. The rerouted traffic pattern took the life out of Ricohoc, leaving the village “a sleepy backwater,” according to Deslatte. “LA 182 was a very busy road and was the only road in Ricohoc, so when it changed over to [US 90], lots of businesses closed and the area suffered,” Deslatte said. “It’s still quite a depressed area ‘til this present day.”

Though US 90 isn’t an interstate, the frontage roads and major exits give it the look and feel of one. Every so often between Lafayette and Boutte, you’ll find a clue as to why: an Interstate shield sign marked “Future I-49 Corridor.” The future major interstate south of I-10—called I-49 South—has been in the works since 1987. The idea is not to build a new interstate, but to transform US 90 into I-49 South, and many parts of US 90 have been successfully upgraded to interstate standards. Proponents of the plan say the new interstate will provide a major and necessary hurricane evacuation route for coastal Louisiana, and that it will provide a key corridor to Canada for freight coming through the Panama Canal. Upgrading US 90 to an interstate with controlled access would likely curb the highway’s status as Louisiana’s most dangerous highway, too.

Our nation’s mostly finished network of highways now connects sea to shining sea, city centers to rural expanses, oil and gas to refineries, and commuters to their jobs and McDonald’s breakfasts. For all the good those highways do, Steinbeck was right. Interstate exits look largely the same: corporate gas stations, huge truck stops, fast food chains, storage facilities, and well-known hotels dominate the expensive on- and off-ramp real estate. If you’ve seen one exit, you’ve seen them all. Perhaps that’s all the more reason to take an old main route through a town and away from an interstate, should you find the time. The march of progress can demolish the past in its path, but some stories aren’t buried too deep beneath the concrete, should we sacrifice some efficiency for a long drive.

Lagniappe: Real Cajun Food… South of I-10 or south of US 190?

For every Cajun making supper in New Roads, there’s a Cajun in Broussard making a wisecrack about how Cajun food doesn’t exist north of I-10.

At some point since I-10 was pieced together in Louisiana—between 1962 and 1974—the nation’s southernmost interstate highway became a folk culinary border of “real Cajun food,” much to the chagrin of real Cajuns north of I-10. Of course, I-10 is not the northern limit of real Cajun food; it’s simply the most obvious geographical border that currently exists. Those who grew up before I-10 was built, however, might claim a different boundary for Cajun food: US 190.

US 190 was presumably the first imaginary border of real Cajun culinary expertise. The highway goes through Krotz Springs and Eunice, so it’s arguably the road to some of the best boudin on the planet. Ville Platte’s disproportionate number of gas station meat markets isn’t far north of US 190, and it’s one of the rare cities in the entire state that has a multitude of smoked ponce options.

The fact that so many people reference either highway in the context of food is an example of how highways can divide communities in many ways, and how interstates can replace highways, even in our jokes.

Christie Matherne Hall writes about culture, waterway exploration, natural disasters, foodways, history, and other threads that need tugging. She splits her time between her day job as a finance writer in Colorado and her other job floating from patio to patio with friends and family in Louisiana.