Peculiar and Incendiary

Julian Moreau’s The Black Commandos.

Published: November 30, 2023

Last Updated: February 29, 2024

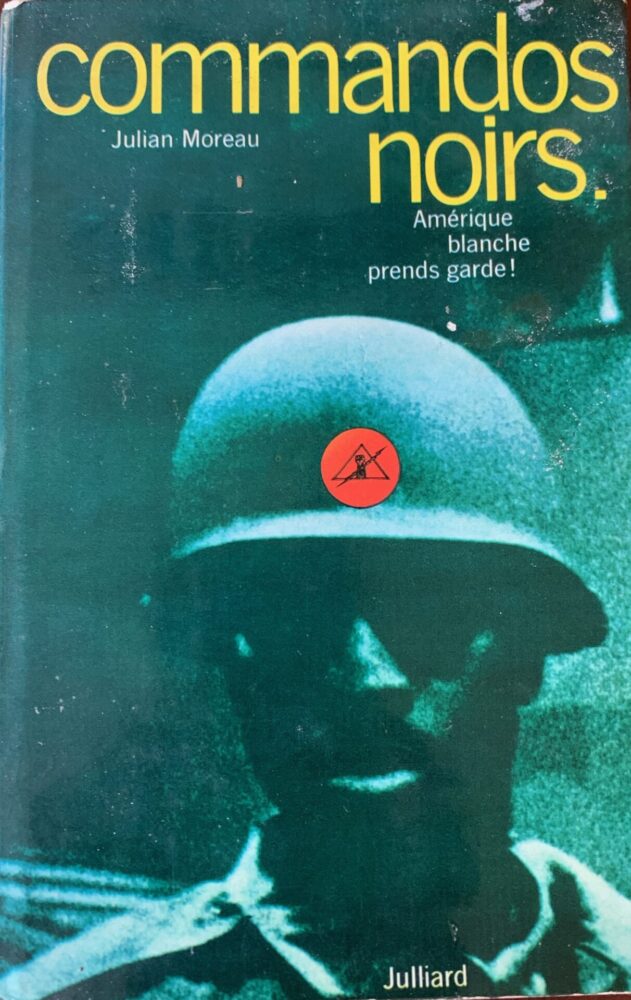

Julliard

A 1968 French edition. The teaser text translates as “White America, beware!”

The Black Commandos is a bad book. That’s not to say the 1967 novel is so bad that it’s good—the book remains egregiously awful, full of puerile plotting, one-dimensional characters, and frequent misspellings. But sometimes a publication deserves attention, perhaps even a wider readership, simply for existing. Joseph Denis Jackson’s The Black Commandos, written under the pseudonym Julian Moreau, despite its overwhelming flaws, merits mention as a peculiar and incendiary outlier in the state and nation’s literary canons.

The novel begins in the Allen Parish town of Oakdale, where the protagonist, also named Denis Jackson, age nine, moved with his mother from New Orleans after his father was killed by cops. Violence follows young Denis there: the violence inflicted on African Americans in the segregated South, “untold humiliation,” Moreau writes, “degradation, torture, lynching, poverty, as well as perpetual and profound ignorance.” One afternoon, while playing a game of marbles, Denis’s best friend Henry is brought down by a stray police bullet meant for another Black youth. Denis swears revenge.

Fast-forward three decades. Denis Jackson has mastered over two dozen languages, published tomes of philosophy and psychiatry, and is a patented inventor and millionaire headquartered in Atlanta. Blessed with an IQ well above 200, he is also immensely strong. “Long years of grueling training,” Moreau writes, “had brought his body to a peak of physical perfection no other man in all history had attained!” Is he suave, sexy, and radiating erotic allure? Jackson doesn’t say—but we know the answer.

Unlike the spandex superheroes he tangentially resembles, Denis Jackson embraces violence first and foremost in his fight for justice. He leads a vigilante group, the National Secret Police of the Negro People of America, a.k.a. the Black Commandos, an elite corps of super soldiers dedicated to strategically assassinating “key members of the racist power structure.” Covertly roaming the country in a fleet of black Cadillacs and flying saucers, the Commandos are armed with chemical and biological weapons, kung fu finesse, and enough artillery to blow up Stone Mountain.

In their first foray, the Commandos attack an Alabama Klan rally, slaughtering the white-robed white supremacists under a torrent of gunfire. “They received no pity or mercy,” Moreau writes, “as they had for generations given none!” With a taste for bigots’ blood, they next target Alabama Governor Malice—a play on George Wallace—executing him with a hatchet in his office. Nicknamed the “Black Demons from Hell” by the media, the Commandos kill a trio of cops who had mutilated and murdered a Black Vietnam vet who was dating a white woman. They stage a second riot in Watts, decimate a group of Mafia dons, and kill more neo-Nazis, crooked cops, and klansmen than I could count.

. . . sometimes a publication deserves attention, perhaps even a wider readership, simply for existing.

Promoting a strategy he calls “vigorous self-defense,” Denis stumps across the nation, under the banner of the Black Liberation Front. “Non-violence is a beautiful way of life,” he tells audiences, “but it can never prevail against violence.” No one speaks up in dissent. Seemingly no women are involved in Denis’s revolution. Rampant homophobia drips from these pages like so much gore. And in the end, the violence, which culminates in the takeover of the state of Mississippi, feels gratuitous, sadistic, and tedious rather than redemptory.

Mainstream publishers, unsurprisingly, rejected this manuscript en masse. Its blood-soaked pages likely have everything to do with Dr. Rev. Joseph Denis Jackson’s decision to self-publish and to do so under the pseudonym Julian Moreau. The Black Commandos, it seems, only found a limited audience. But Charles Peavy, a University of Houston literature professor at the time of publication, wrote early and often of the novel in academic journals, touting it as “the first attempt to incorporate the standard devices of pop culture manifested in comic books, television, science fiction, and spy-thrillers as a vehicle for black consciousness.”

Scant details are available about Dr. Rev. Joseph Denis Jackson’s life. But a postscript to the novel’s second edition, published by his son Julian in 2013, fills in some of the biographical blanks, along with some extraordinary claims. Per Julian’s account, Dr. Rev. Joseph Denis Jackson was born in New Orleans in 1929. He earned eight degrees, including an MD, JD, PhD, and ThD. Like his alter ego, he was also a bodybuilder, able to deadlift 570 pounds. Inspired by his passion for comic books, which lacked a character who directly confronted American racism, Jackson penned The Black Commandos. Before writing the book, Julian claims, Jackson coined the slogan “Black is beautiful and it is so beautiful to be black” for Martin Luther King Jr., thus earning Jackson the nickname “the father of the black pride movement” (Stokely Carmichael would like to have a word). Yet above all these accomplishments, Julian asserts, it is Jackson’s book The Black Commandos that made him “one of the most impactful leaders, an unsung hero, of the civil rights movement.” According to the reprint’s back cover, rumor has it the Black Panther Party considered the book required reading.

So what value does The Black Commandos hold for modern readers? Does it showcase a manifestation of what, in 1968, the psychiatrists William H. Grier and Price M. Cobbs termed the “black rage” of the period? Is the book a progenitor of the blaxploitation film genre that would come to dominate the 1970s? Or is this book an amateur take on speculative fiction, an explosive fever dream of a violent revenge fantasy? Why am I reading—and reviewing—such an objectively bad book, I asked myself several times while mired in its pages. Is it a good practice to open ourselves to books we could easily dismiss as dumb, dangerous, or obscene? Does my whiteness automatically exclude me from resonating with whatever depths the book contains?

Regardless of the book’s literary merit, Joseph Denis Jackson was tapping into a feeling whose expression still echoes today. In an interview with Peavy published soon after the novel’s release—the sole interview with the author that I could find—Jackson revealed that the book was written as both a warning for white Americans and catharsis for Black Americans. “I am not interested in destroying the white people, but in saving them,” Jackson said. “White people need to see that the sickness of racial prejudice which motivates them against the Negro is ultimately self-destructive and will only lead to disaster.”

But for all his triumphs against white supremacy, the life of Denis Jackson, the character, still ends in tragedy. The book’s final line reads as follows: “In spite of all the killing, in spite of his complete and astounding success, Denis Jackson was still a very angry man!”

In contrast, perhaps the life of Joseph Denis Jackson ended with a sense of peace; in Julian Jackson’s reprint edition, this emphatic final line is omitted. A brief 2008 Atlanta Journal-Constitution obituary for the Rev. Dr. Joseph Denis Jackson mentions nine children, no partner(s), and not a single reference to The Black Commandos.

Rien Fertel is the author of four books, most recently Brown Pelican.