Current Issue

Perennial Heartbreak and Renewal

Twenty years of post-Katrina New Orleans

Published: August 29, 2025

Last Updated: September 2, 2025

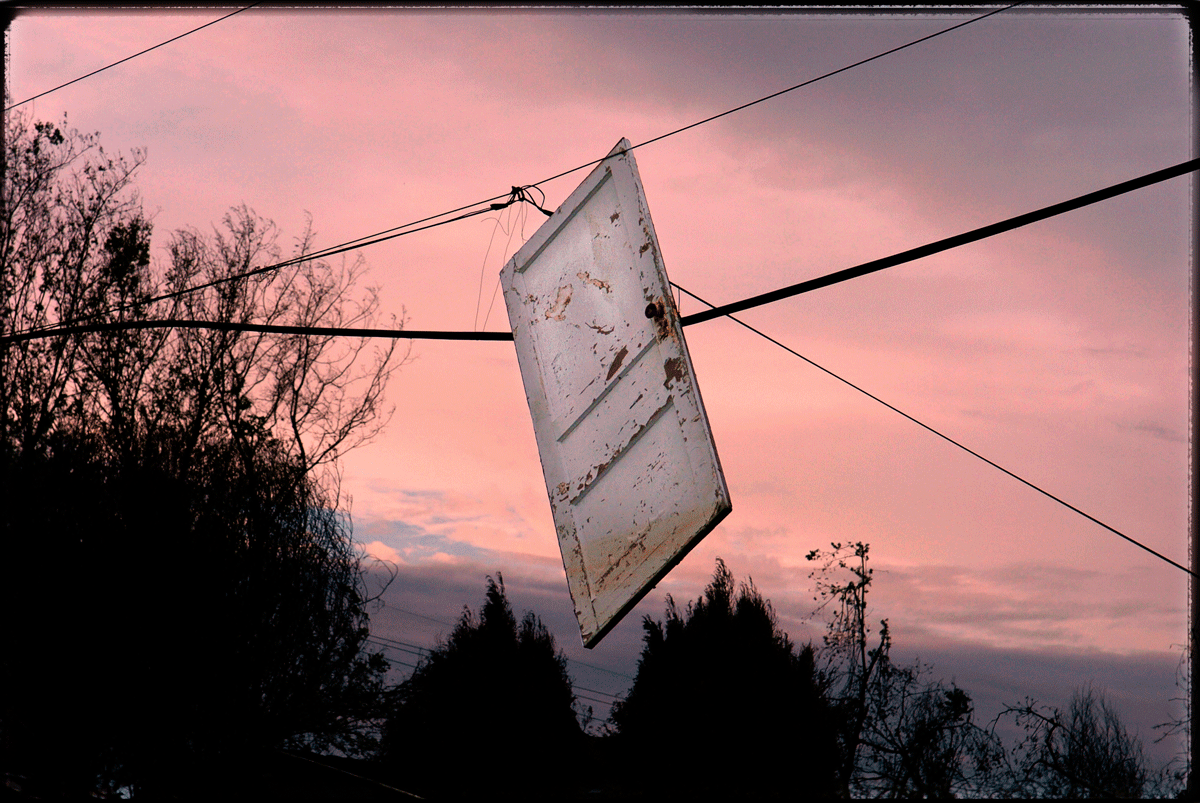

Photo by Kathy Anderson/The Times-Picayune

A door left suspended in power lines by the post-Katrina flood.

I didn’t know my city well until high school, which is when I began to study her history, her tragedies, and her people. Receiving her name from French colonists in 1718, New Orleans is one of the South’s oldest cities. In a land sometimes rife with bigotry, the early town was one of the most diverse, a mix of Native American, African, French, English, Creole, Cajun, and African American.

My halcyon days were the nineties. Everyone I knew wore NFL Starter jackets and Bally Animals sneakers. Everyone I knew was musically gifted and free-spirited. Sometimes I’d find boys behind school drumming a bounce beat as a girl rapped, laughing as she used a pickle for a microphone. I was nerdy, shy around everyone except for my closest friends, awkward enough that strangers tended to make fun of me. But the city loved me. I could never get too down because of the constant joie de vivre: cookouts, second lines, Mardi Gras parades.

Love was the dominant mode in New Orleans. I’d see a woman pick up a crying neighborhood kid, and rock them to quiet. At the corner store, the owner gave away free candy. Tourists stopped and listened as a local broke into song, doing a perfect imitation of Irma Thomas, Ernie K-Doe, or Mahalia Jackson. One of the youngsters at the summer camp where I worked after my senior year could transform into Louis Armstrong, right down to the gravelly voice and facial expressions. It unnerved me that someone not much younger than myself could so easily tap into an old spirit.

But New Orleans was an old spirit. The city held her superstitions close and without pretension. New Orleans taught me not to walk under ladders, split posts, or eat everyone’s gumbo. If you were a decent person, you always said hello to passersby.

Then I went to college, expanding my worldview. Learning about ancient Mesopotamia and the difference between Mexican Spanish and Spanish Spanish shifted my focus. I didn’t think so much about home anymore, even though I was still in the city. I assumed I would leave eventually. Explore the possibilities of our huge nation.

But Katrina hit.

My wife and I lit out west from New Orleans in a caravan of aunts, uncles, cousins, and play kin. We passed through Baton Rouge and Monroe, LA. Houston and El Paso, TX. Scottdale, AZ, too.

After Katrina dissipated, Hurricane Rita took up the chase. We dropped off family along the way until eventually it was just me and my wife. We stopped in Los Angeles. Any further west, we would have wound up in the Pacific.

Our time in Los Angeles was short lived, and we had the kind of adventures one has when the world is ending. Exploits you’d have a hard time explaining to St. Peter at the Pearly Gates.

Residents of Nelson Street Lisa Burns and her sons Delton and DJ watching the water rise following Katrina’s landfall. Photo by Kathy Anderson/The Times-Picayune

I don’t have to tell you Hurricane Katrina was a terribly stressful time. We were unable to return to the city, which was flooded. TV showed how bad things were. People left to suffer at the Convention Center. Bridges out of town blocked by law enforcement. We saw on a news report the flood water lapping the street sign at the corner of my house, but not the house itself.

After I returned, the city looked like the River Styx. Everything was covered in gray cake. But then cranes appeared in the sky, funded by federal money. The federal money came as an apology of sorts, I suppose. After all, it was the federal levee system that failed. In the wake of the new building came a wave of mostly younger people who moved in seeking adventure and opportunity. But the unspoken story was that about one hundred thousand African Americans had been displaced.

Somewhere the ancestors were crying, just as the living cried. Sometimes a place dies even as it holds you in its arms.

Month after month, new incidents demonstrated how New Orleans was changing. Many of the public schools were suddenly run by private companies. Strange gumbo recipes appeared on social media, recipes that included white beans, kale, and other horrific ingredients. They called it stew. Gumbo Stew. Then, there was a big to-do over whether brass bands should be allowed to play downtown and in the French Quarter after 8 pm, something they had been doing since Jesus was young. Somewhere the ancestors were crying, just as the living cried. Sometimes a place dies even as it holds you in its arms.

I wanted to make this essay more straightforward. I was going to list a bunch of dates, federal dollar amounts, year over year population shifts. But mere facts don’t do justice to the last twenty years. The alternative was a purely personal exploration of my struggles and triumphs. Yet if I laid all my mixed feelings out, I’d need another three hundred pages to tell the tale. The truth is although I’ve written about New Orleans and Katrina many times, I’ve come to accept I may never be able to provide a clear meaning of the circumstances, even to myself.

But here’s what I can say.

New Orleanians remember the uncertainty of late August 2005. We didn’t know when the floodwater would recede. We didn’t know when we’d be able to return to our homes. We didn’t know if the city would ever feel like home again. Some suggested that the municipal authorities should let flooded areas become green space. That was an insult. Since eightypercent of the city flooded, that would mean making most of the city green space. But a city is more than a park. A city is for the people.

Before Katrina, a major concern was depopulation and how to stop it. Articles about brain drain appeared as often as the new moon. Then the storm came and later a storm of money. The federal government provided money for infrastructure and entrepreneurs. Brain drain was no longer a problem in early post-Katrina New Orleans.

Within a few years of Katrina, New Orleans was the fastest growing city in the nation. New skyscrapers and warehouse apartment buildings dotted the land. Gastropubs and yoga studios proliferated. Brass bands were in fact reprimanded for playing music in public after sunset; their fliers were ripped from light poles. The city was officially gentrifying.

Perhaps New Orleans has died many times. But it has also resurrected.

In the Gulf of Mexico, an oil spill maimed the fishing industry. But the crawfish and catfish would return. We ate them out of habit despite their oil seasoning. West of the city, chemical plants spewed particulates into the air. On a windy day, those Cancer Alley particles fell on café tables and playgrounds where little girls frolicked. Many nights, one of the plants released a great plume of flame that seemed to say, “I am.”

Both of my parents had cancer.

I don’t want to give the impression that New Orleans was ever a paradise. If the city was a person, she’d always been here for a good time, not a long time. She’s probably paid a few visits to the local jail after having too much fun. But she was the life of the party, until she wasn’t. Even the wildest child can grow up. To paraphrase John Huston in Chinatown, if you live long enough, anyone can come to be seen as respectable.

In September 2024, I sat at the table of a popular Uptown restaurant called Val’s. I saw visions of particulates in the air I breathed. I wondered how much oil, lead, or mercury was in my food and drink. I questioned how my body was being changed.

I told myself to cast those thoughts aside. I was an optimist, and my job was to smile. But it wasn’t a happy occasion. A pair of old friends were leaving town for good with their small daughter. Let’s call them Sylvie, Marco, and Mia.

I had started to notice a pattern. Little moments that seemed to point in a general direction. Like how a weathervane catches the high wind before you feel it on the ground. I’d receive a text message from a friend I hadn’t heard from in a while. “Hi, Maurice, this is Sylvie. We’re moving to Pennsylvania next week. I found a new job and Marco’s mom will help with Mia. Let’s get lunch before we let go.” We’d eat, say, delicious Latin-inspired food, and I would suddenly feel very old.

As a new writer years ago, I was excited by the waxing energy of the city. By 2019, it seemed there was a literary event in town every night. Once I knew no writers. Now, most of the people I knew were writers. And they were leaving like drops of faucet water in the night. One by one.

I’ve got a half dozen friends preparing to leave even as I write this sentence.

This isn’t just anecdotal either. Stories have been appearing in the paper for years. I recall an op-ed by a recent transplant who said that she couldn’t afford to send her child to the parochial school she’d thought would be best; relying on private schools was tantamount to paying a tax for having children. Another article mentioned how French Quarter restaurant workers were having a harder time finding affordable housing and that increased parking meter rates had forced some of those with cars to park over a mile away, near Cresent Park. Others cited a lack of confidence in local government, being worried about frequent water boil warnings, and crime. Or that city might be washed away by a future hurricane.

By early 2025, we learned that the New Orleans metropolitan area was the fastest shrinking region in the country. Synthesizing all the information, I saw a theme as to why people were fleeing in great numbers: we didn’t have hope.

In some countries, citizens must apply to move from one region to another. But in the United States of America, you can vote with your feet. Although I was sometimes disgusted by all the newcomers who arrived between, say, 2006 and 2020, I never blamed them. To a certain kind of adventurous spirit, New Orleans must have looked like an amusement park. A place where any kind of future was possible. But the literal amusement park in my childhood neighborhood, New Orleans East, never reopened after the storm. This year, a bulldozer pulled down the remains of the Mega Zeph rollercoaster that I screamed on in happier times.

The Mega Zeph Roller Coaster at Six Flags New Orleans, still fondly remembered by locals as its original name, Jazzland.

I don’t mean to imply that New Orleans is finished. Stories of the city’s death have been greatly exaggerated many times before. New Orleans burned to ashes in 1788 and again in 1794. In 1853, yellow fever killed eightpercent of the population. In 1965, my mother, then twelve years old, nearly drowned in the flooding from Hurricane Betsy. One of her neighbors was killed. Between 1950 and 1990, deindustrialization and white flight saw large numbers of residents moving out of the city and into the suburbs or out of state. In 1960, New Orleans had its highest population: 627,525. Today, the population is just over 350,000.

Perhaps New Orleans has died many times. But it has also resurrected. In research for this essay, I was initially convinced of an ill wind. My imagination told me that the city was in its death rattle. But I was wrong. Many have left, but many are here. There are still festivals practically every week. There’s always a band playing on Frenchmen, Oak, or Bourbon Street. Just today, a friend who has lived in Baton Rouge for years walked up with a huge grin. “I’m finally moving to New Orleans,” she said. “I’m ready for my life to start.”

Maurice Carlos Ruffin is the author of the historical novel The American Daughters as well as The Ones Who Don’t Say They Love You, a One Book One New Orleans selection, a New York Times Editor’s Choice, and was longlisted for the Story Prize. Ruffin is a professor of Creative Writing at Louisiana State University.