Summer 2009

Peru, Who Knew?

Creole connections exist between South Louisiana and South America

Published: January 25, 2022

Last Updated: March 8, 2022

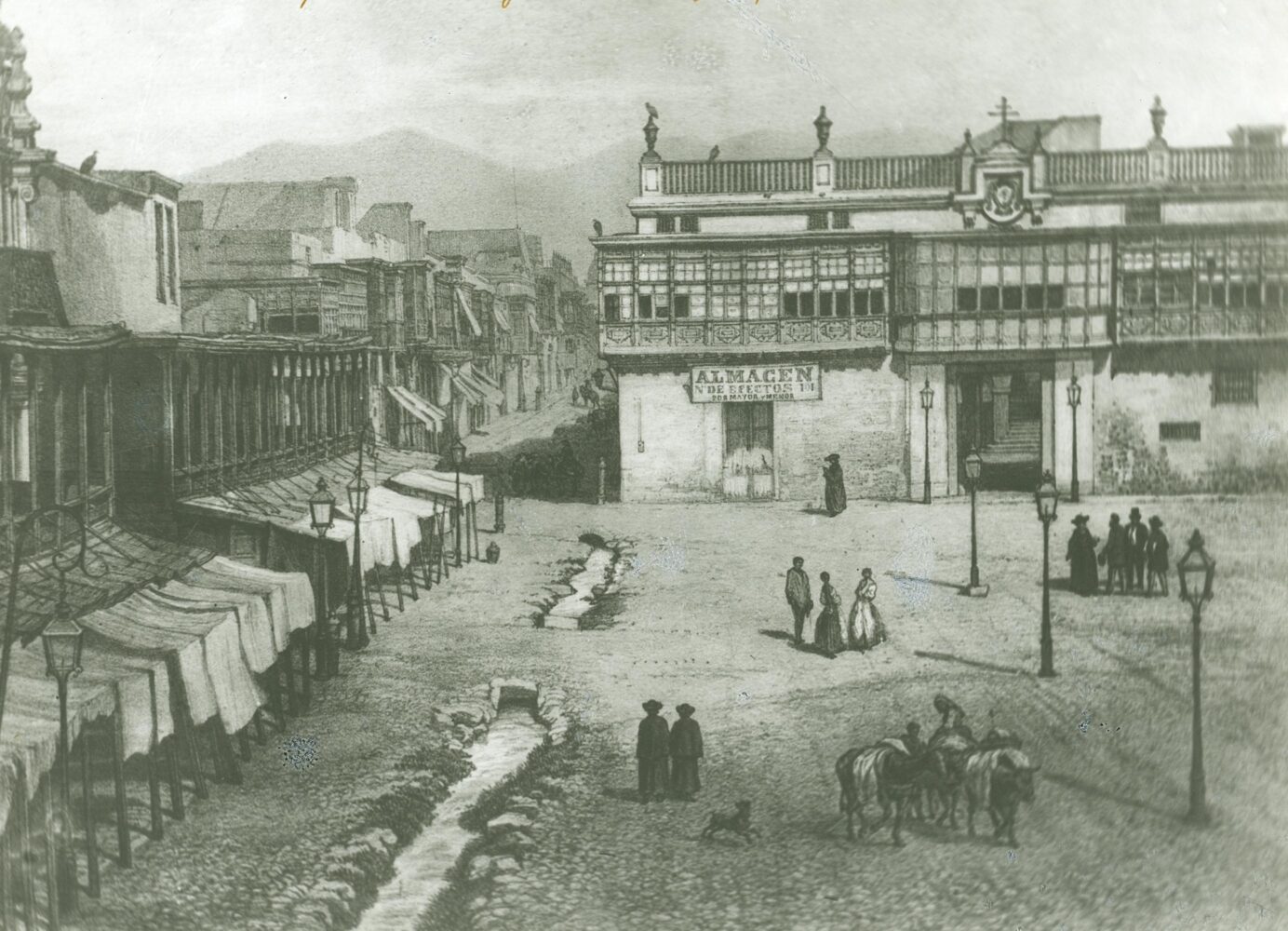

Museo Naval de Peru via Wikimedia Commons

An anonymous etching of a square in Lima, Peru, ca. 1854.

I arrived in Lima on Mardi Gras fully expecting to see the city filled with masking, parading folks, but instead found the streets to be clogged with traffic that I would learn is a part of everyday life in Peru’s capital city. My second surprise was Lima itself, a huge, sprawling city where the suburbs hug the Pacific Ocean, muddy and turbulent, nothing like the Atlantic with which I am much more familiar. While preparing for my lectures, which were to be about African American culinary culture, I took time out to read up a bit about Black history and culture in Peru. I, like many others, was unaware of the large role played by Africans and their descendants in the culture of Peru, a country where Black history is often underground, if acknowledged at all. I learned that enslaved Africans were originally brought to work the mines and the cane fields that were established along the coasts south of Lima. Africans in Peru arrived early and there are records that indicate that in 1547, a few decades after conquest, there were seven known Black street vendors (probably more) selling food and other goods in Lima’s main plaza for their masters’ benefit. The more I read, the more I became intrigued by similarities that connected Peru to New Orleans and the world of the African Diaspora that I have long studied.

Perhaps the most startling revelation is that the word “creole,” which is used throughout the African Diaspora, may have originated with Peruvian slaves. As recently as 1989, Spanish etymologists Joan Corominas and José A. Pascual declared that while the Portuguese origin of the word creole is undisputed, it may have ultimately been African in origin. They cite Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, who wrote in Peru in 1602:

“It’s a name that the negroes invented … it means among the negroes ‘born in the Indies’; they invented it to distinguish those … born in Guinea from those born in America, because they consider themselves more honorable and of better status than their children because they are born in the fatherland, while their children are born abroad, and the parents are offended to be called criollos.”

The cultural connection of the Creole world was very much in evidence during my brief stay in Peru. It is evident in the casual lifestyle and the affectionate way that even strangers greet new acquaintances with two kisses—one on each cheek. It is visible in the architecture that in southern-Spanish style turns a blind eye to the street while inside lurk patios and flowered courtyards. It is witnessed in the casual adherence to the ticking clock—appointments routinely are a bit later than planned, yet always right on time. It is there in the elegant gliding dances like the marinera and the Creole waltz that I witnessed at Don Porfirio, one of the small dance clubs called peñas. It is also there in the music that often boasts a haunting underlay or is punctuated by intricate percussion rhythms. Perhaps, though, the most startling Creole connection in Peru for me was the food.

Peru is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world with a marketplace that boasts a staggering array of fish and an abundance of fruits and vegetables. A visit to one of the local markets revealed everything from the apples and pears of temperate climes to the passionfruit and mangoes of the tropics. The meat aisles displayed an array of pork products and silently testified to a Peruvian love of innards including beef heart for anticuchos (skewered barbecued tidbits) and tripe, which is sold in three different types: pocket tripe, blanket tripe, and book tripe! Incan traditions were evident in the array of potatoes that were sold both whole and pre-julienned and in the abundance and diverse varieties of corn. Then there were the guinea pigs—cuy—that are a delicacy to some; they sit in their cages, pink noses quivering, as though they know that their future lies in the oven, not on a rotating wheel in a cage.

“El que no tiene de Inca tiene de Mandinka.” It roughly means those who don’t inherit from the Inca, inherit from Africa.

Food that was sold on the streets by enslaved African in the sixteenth century continued to be sold in the ensuing centuries. By the nineteenth century, street vendors of all hues were selling dishes that form a culinary link in the African diaspora. Some sold fritters prepared from flour, eggs, and cinnamon that were drizzled with a syrup made from sugar cane and each vendor’s special ingredients. Others sold sweet breads or cakes. Still others sold fresh melons and the typically Peruvian drink known as chicha morada. Prepared from the kernels of dark maroon corn, deep purple chicha can be a benign cooling beverage or take on prodigious alcoholic qualities if allowed to ferment. Images of nineteenth-century street vendors sketched by artist Manuel Atanasio Fuentes are Peruvian cousins to those done in New Orleans by Lafcadio Hearn or Leon Frémaux. The dishes that they depict are related as well. Fritters like buñelos mirror calas and beignets; arroz con leche is rice pudding; and melcocha is a peanut patty that is similar to a praline.

I met the Peruvian Leah Chase: a woman who embodies the wisdom of the Peruvian Creole kitchen. Teresa Izquierdo, whose restaurant is jokingly named El Rincon Que No Conoces (The Spot You Don’t Know) is Peru’s most renowned Black cook. Daughter of a cook, she grew up in the kitchen and found her way back to it. As I have often done with Mrs. Chase, I sat at a side table in her restaurant, and we shared family recipes for dishes like pigs’ feet and pork crackling with each other and laughed at how we’d both grown up eating lard and bacon grease. She spoke with me about tacu tacu, rice and beans Peruvian style, and I told her about hoppin’ john and red beans and rice. Our time together was, not surprisingly, too short, but it cemented my thoughts about the cultural and culinary relationships of all those who live in areas where Africans have scattered.

Too soon it was time to leave Peru, but I had learned how much more I needed to learn. On the day I left, my new friends gathered together, and we celebrated with a traditional Peruvian dish, cebiche, with a twist. The traditional marinated raw fish dish was served at a local cebichería, but the Japanese-Peruvian owner had cut the fish in strips in the manner of sushi as opposed to the usual chunks. The cebiche preceded a fried fish that would have been right at home in a small restaurant near the Treicheville market in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, or on one of the side streets of Benin’s capital, Cotonou. It was called chita, a crisply done deep-fried fish topped with a slaw of thinly sliced raw onion mixed with searingly hot chile and served with chunks of corn. Washed down with beer and accompanied by good conversation, the meal reminded me of many consumed on excursions past.

On my flight back to the United States, I kept repeating a saying I had learned that expressed the deep vein of African culture that runs through Peru: “El que no tiene de Inca tiene de Mandinka.” It roughly means those who don’t inherit from the Inca, inherit from Africa. The saying connected me to Peru and placed Peru in the cultural and culinary curve that also includes New Orleans. Now, when asked about my trip to Peru, I simply say “Peru … who knew?”