Fall 2024

“Poison Portraits”

A toxic silhouette album provides an intimate look at early Louisianans

Published: September 1, 2024

Last Updated: December 1, 2024

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Bache’s album features more than 600 portraits from territorial Louisiana.

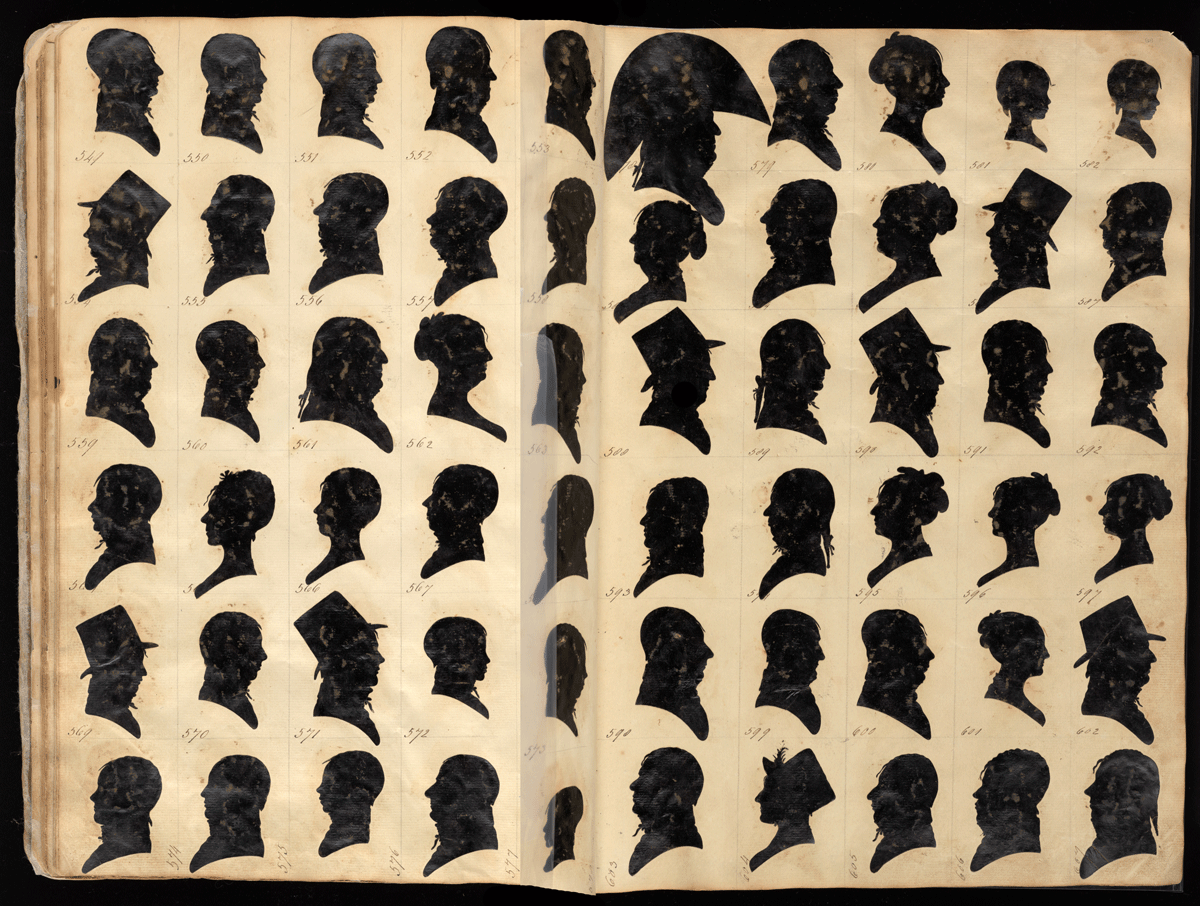

Somewhere in collection storage at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Portrait Gallery lies an oversized ledger with a cracked leather spine and spotted press-board cover. Inside are yellowed pages dating to the early nineteenth century. They’re filled with over 1,800 small, intricately shaped paper silhouettes made by Englishman William Bache between 1803 and 1812. More than a third of the portraits depict individuals living in and around New Orleans in the year after the Louisiana Purchase—and most represent the sitters’ only known likenesses.

Acquired by the Smithsonian nearly two hundred years after their creation, the portraits also contain something unexpected—and dangerous: arsenic. A semi-metallic element, arsenic was sometimes used in small quantities in pigments and household products, including cosmetics, in the nineteenth century. How it ended up infused in the pages of a portrait silhouette album is unclear, but its presence represents a significant hazard to conservators, curators, and other would-be users.

In 2021 the National Portrait Gallery secured a grant through the Getty Foundation’s Paper Project initiative to safely digitize the album in its entirety. Conservators wore hazmat suits and respirators, minimizing contact with what Getty program officer Heather MacDonald called Bache’s “poison portraits.” Smithsonian curator Robyn Asleson researched sitters’ identities, combing through contemporary newspapers, city directories, and census records. The result is the creation of a National Portrait Gallery website focused on Bache and the identities of his sitters. The site is a treasure trove of visual culture, providing a unique look at individuals and families—from everyday people to noted figures—from the early American Republic.

Sworn enemies Governor William C. C. Claiborne and Daniel Clark feature on separate pages of Bache’s album. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

William Bache arrived in New Orleans sometime in the fall of 1804. An itinerant portrait silhouette artist, Bache had emigrated from England to Philadelphia in 1793, and in 1803 embarked on a nine-year jaunt through seven East Coast states (Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and Virginia), Cuba, and the recently formed Territory of Orleans. He carried with him the tools of his trade: black vellum paper, sharp scissors, candles, and a physiognotrace—an instrument that uses two implements to trace facial outlines. One is controlled by the silhouette artist, allowing the artist to sketch the contours of a sitter’s head onto a candle-lit canvas. The other is a mechanical arm that mimics the artist’s sketch in miniature against a piece of black or blue paper or fabric. Once the outlines of the sitter’s profile appear on the paper, the silhouette artist removes it from the device’s frame and folds it over once or twice before cutting out multiples of a finely detailed silhouette.

With roots in 1780s France, the physiognotrace revolutionized the capture of an individual’s likeness and democratized portraiture. Predating photography by some fifty years, the device allowed individuals and families who might not have means to commission a painting or sculpture to receive a portrait silhouette for a modest fee. Newspaper advertisements, including French and English versions published in November 1804 in the Louisiana Gazette, show Bache offering clients “four correct likenesses, neatly cut in Vellum paper for one dollar,” or the equivalent of about twenty-five dollars in today’s money.

Early-nineteenth-century example of a physiognotrace. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Bache’s physiognotrace, which could be used without touching the sitter’s face, was of the latest design, having been patented in early 1803 by Bache and his partners Augustus Day and Isaac Todd. As he traveled through North America and the Caribbean, Bache pasted copies of each silhouette into his album, likely using the assemblage of portraits to advertise his services. Early in his travels, Bache numbered each portrait, including a keyed index to approximately 770 of his sitters in the album’s final pages.

In New Orleans, Bache set up shop on Royal Street near the intersection of St. Ann, close enough to St. Louis Cathedral and the military parade grounds (today’s Jackson Square) to entice churchgoers and soldiers alike. The number of portraits Bache created during his one-month sojourn in New Orleans suggests his services were wildly popular. Of the nearly 2,000 portraits pasted into his album, 672 were made in New Orleans. Among Bache’s clients were some of the city’s most notable movers and shakers, including Louisiana’s first American governor, William Charles Cole Claiborne, who posed twice—once in military dress, once as a civilian; Claiborne’s soon-to-be-enemy Daniel Clark, who had not yet wounded the governor with a shot to the groin during a duel; Baroness Micaela Almonester de Pontalba, whose thirty-two stately townhouses still flank both sides of Jackson Square; Colonel Michel Fortier II, who went on to lead one of two free Black battalions in the Battle of New Orleans; and many more.

Indeed, the album is a veritable who’s who of early American Louisiana, full of people now most familiar as street, neighborhood, and city names: Mandeville, Chalmette, Bonnabel, Kenner, Bellechasse, Marigny. Yet the majority of the sitters appear to be ordinary people, including priests, children, free people of color, new brides and bridegrooms, and even whole families dressed in their Sunday best. Many a name still familiar to twenty-first-century New Orleanians—Dejean, Duplessis, and Charbonnet to name a few—can be found in Bache’s silhouette collection.

Also included are a number of intriguing silhouettes, particularly those created in Cuba, that Bache left unnamed and unnumbered. The Cuban silhouettes, made between December 1804 and May 1806, include many people of African descent, created as Bache went door to door, physiognotrace in hand to solicit business. Might some of the individuals whose likenesses Bache captured in Cuba have been among the nearly ten thousand men, women, and children—refugees from the Haitian Revolution expelled from Cuba—who arrived and settled in New Orleans and the surrounding areas between 1808 and 1809? Bache’s album prompts many questions, and for those interested in a glimpse of Louisianans in their first decade as Americans, the album is an exceptional resource.

To view the William Bache Silhouettes microhistory website, including a timeline of his travels, high-resolution digital images of each portrait, and an index to identified sitters, visit npg.si.edu/bache.

Erin M. Greenwald is a historian and public humanities professional living in New Orleans. Formerly editor in chief of 64 Parishes, she is now working on a biography of Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, sieur de Bienville. You can find her at workinghistorian.com.