“Pumps and the Opera”

New Orleans was an operatic capital, with people of color often at the fore

Published: November 30, 2023

Last Updated: February 29, 2024

Gift of the Crescent Club, The Historic New Orleans Collection

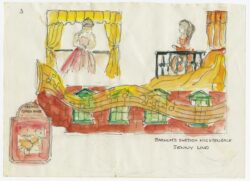

As late as 1986, memories of the Jenny Lind craze inspired Mardi Gras floats, as in this Proteus design by Herbert Grant Jahncke.

Since the manuscript’s recovery, Opera Créole, a local opera company formed in 2011 to perform lost or rarely performed works by nineteenth-century New Orleanian composers of color, has set their sights on presenting the opera’s world premiere. A production is planned (funding permitting) in partnership with Opera Lafayette, to be performed in New Orleans, Washington, DC, and New York City in 2025–2026.

For mezzo-soprano Givonna Joseph, Opera Créole’s artistic director, bringing Dédé’s work out from the shadows is not solely a mission-driven matter of restorative justice for neglected Black composers. Long before Opera Créole was even a twinkle in her eye, she loved singing Dédé’s “Mon Pauvre Coeur” for the arresting beauty of his song that speaks so achingly to unrequited passion.

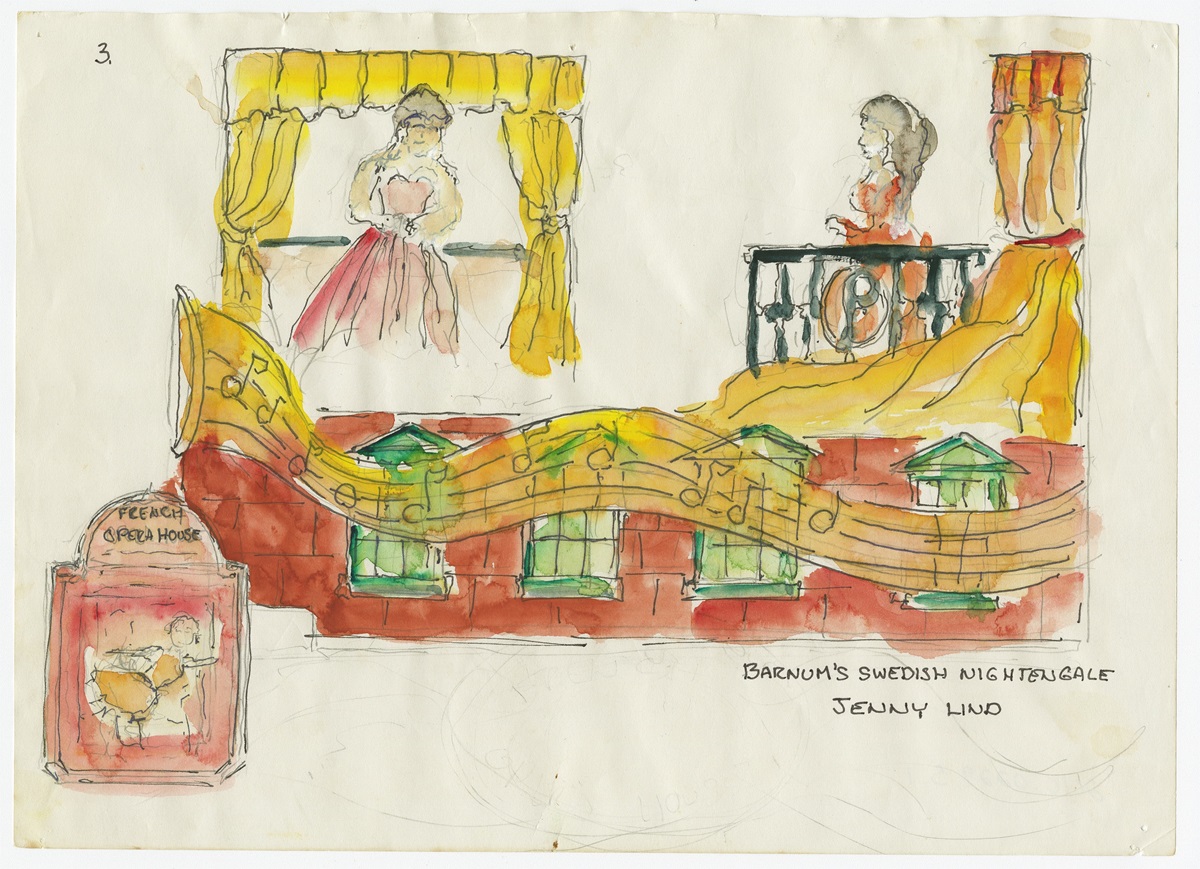

Portrait of Edmond Dédé. Gift of Al Rose, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Joseph mainly credits her mother with her lifelong devotion to opera singing—well, her mother, and tenor Mario Lanza, and maybe The Ed Sullivan Show, a variety television program with a mass cross-cultural audience that ran from 1948 to 1971. It routinely featured opera stars as part of popular culture along with cabaret, comics, puppetry, plate spinners, and whirling dervishes.

“My mother had to quit school after eighth grade because her parents were so poor and she had to help out,” Joseph told 64 Parishes. “But the appreciation for culture from that woman was just amazing. I remember watching my mom’s reaction to seeing Mario Lanza on TV, and she was transfixed.” After that Joseph started singing and has never stopped. “I was looking at my mom, how much she loved that.”

As a college student at Loyola University in New Orleans, she was recruited to be part of the student chorus in a production of Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin at the New Orleans Opera. She had never even been to see an opera before that. It was a first for her parents too, and they sat rapt through four and half hours of German intensity. “When I stepped off into this world, my dad said, ‘You know, we’ve got a civil rights movement going so that you can be whoever you want to be. Our people are fighting for that.’”

In 1796, as now, street drainage was a vexing issue in the French Quarter, which like much of the city sits in a topographical basin. To get there, operagoers faced an unpleasant trudge through puddles, mud, refuse, and manure. “The women would leave home in whatever they’d been wearing, with someone, probably an enslaved person, carrying their evening wear,” Joseph explained. There was a place at the theater for them to wash their legs and get dressed.” Enslaved people too were welcome inside but relegated to restricted seating. “It’s important to realize when you write about opera in New Orleans, I want to really make it clear that it belongs to our people as well,” Joseph said. She recalls reading an account by a historian “expressing amazement at coming to the French Quarter and seeing enslaved people pushing carts and singing operatic arias in French.” But she says such sights would not have been uncommon. Opera was in the air.The Théâtre St. Pierre, built in 1792 on St. Peter Street between Royal and Bourbon, was New Orleans’s first Francophone theatre, financed by two Parisians while Louisiana was still under Spanish colonial rule. It’s long gone of course, razed after the fire of 1816. In the spring of 1796 the Théâtre St. Pierre presented André Ernest Grétry’s opera Sylvain, after the production’s extended run at the Opéra-Comique in Paris, and this was the first documented opera production in New Orleans. Despite its depiction of a taboo, cross-class romance and its theme of championing peasant land rights, the one-act opera was known as a favorite of France’s late queen, Marie Antoinette, who’d met her fate in the Place de la Révolution only three years before.

Operas still in the repertoire today were first premiered in North America in New Orleans, works such as Rossini’s L’Italiana in Algeri, Donizetti’s Anna Bolena (with its electrifying double trills and high E flat), and Bellini’s Norma.

The opera was a draw with its stirring overture, encouraging flutes, invigorating violins, and overall bright and lively musical explorations. Thematically, land justice issues were alive in Louisiana as grants, sales, transfers and exchanges were dealt like cards at a blackjack table by agents of multiple colonial powers—monarchies in Spain and Great Britain and a revolutionary republic in France, which even after the fall of the Ancien Régime fought to maintain its imperial holdings. Into this dynamic swirl of contestation and contingence, opera found its niche, took hold, and proliferated.

“Pumps and the opera saved New Orleans,” Joseph joked, referencing the city’s need for active drainage. The city became a bona fide international opera capital, with multiple opera venues producing whole or partial seasons. Operas still in the repertoire today were first premiered in North America in New Orleans: works such as Rossini’s L’Italiana in Algeri, Donizetti’s Anna Bolena (with its electrifying double trills and high E flat), and Bellini’s Norma. “We were premiering these operas, we were having a lot of French composers and French teachers coming into New Orleans,” Joseph said. “And a lot of our local musicians were trained in Paris, our free men of color were accepted into the Paris Conservatory.”

Victor-Eugène McCarty was an accomplished pianist and composer, best known for publishing 1854’s Fleurs de salon: 2 Favorite Polkas. Joseph recounted that McCarty, one of the earliest prominent free Black composers in New Orleans, was on one remarkable occasion kicked out of the city’s French Opera House. He bought a ticket to attend a performance, for a seat in the white section. This was during Reconstruction, when the theater was “supposed to be integrating.” He was allowed to purchase the ticket but not allowed to take his seat. In solidarity people of color refused to buy any more tickets there to answer the insult. It landed. “At the end of the season, the French Opera House didn’t have the money to send their singers back to France,” Joseph said.

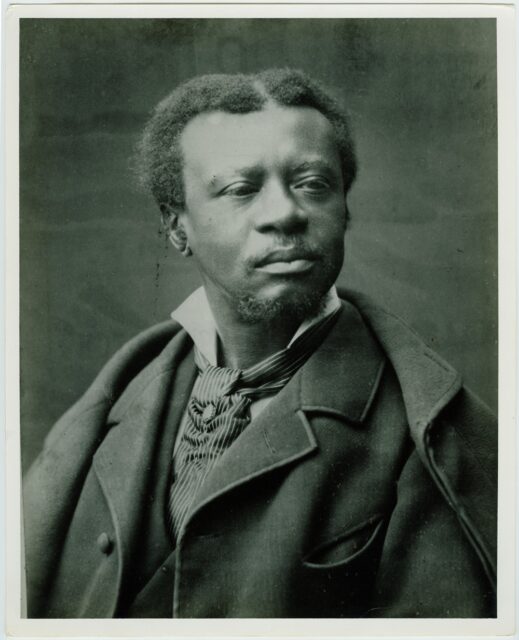

A print imagining the French Opera in its heyday. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

In New Orleans and the Creation of Transatlantic Opera, 1819–1859, music scholar Charlotte Bentley analyzes transnational relationships—both connections and disruptions. Her most salient insight is that New Orleanians, via opera, came to see themselves as residents of a global city with “an exceptional character” on a par with the European capitals with whom their opera houses exchanged repertoire and artists. In their self-perception, they were not provincials in a remote colonial outpost, but participants in a global conversation encompassing not only art but also rights, duty, sacrifice, and sometimes revolution—all delivered in high style.

Joseph, who is also an instructor of music history at Loyola University New Orleans, loves to tell her students about the time when Jenny Lind, celebrated as the “Swedish Nightingale,” arrived at the port of New Orleans. The year was 1850; Lind was en route from Havana, touring from Cuba to Canada. Her impresario, P. T. Barnum, had whipped up such a frenzy about the soprano that the tour had to contend with what came to be called “Lind Mania.” To avoid its worst effects on the main attraction, Barnum hired a Lind lookalike and sent the decoy’s carriage out first for the throngs to follow, allowing the singer to prepare for her performance in peace. It clearly tickles Joseph to imagine an opera singer as the object of such a storm of emotion in New Orleans. Her life’s work is to rekindle that passion in the city of her birth. “I can only do so much on my own,” she admitted. “We’re looking at how to bring us [as a city for opera] back to this highly respected, national level.”

For Joseph, the transnational connections she’s made via Dédé’s vocal compositions continue to exert a kind of moral force that helps to guide her steps with regard to the current project. In July Jean Marie Schevin, Dédé’s great-grandson—a man she had not known existed—reached out. He’d stumbled across a podcast episode about his great-grandfather and the work of Opera Créole; now he was planning a trip to New Orleans. She in turn made plans to greet him—with a special performance of his ancestor’s beautiful music. A reception to welcome him home.

Frances Madeson is a freelance movement journalist, feature writer, and author of the comic novel Cooperative Village.