Fall 2021

Quarrels with America

Robert Stone's A Hall of Mirrors

Published: August 31, 2021

Last Updated: December 1, 2021

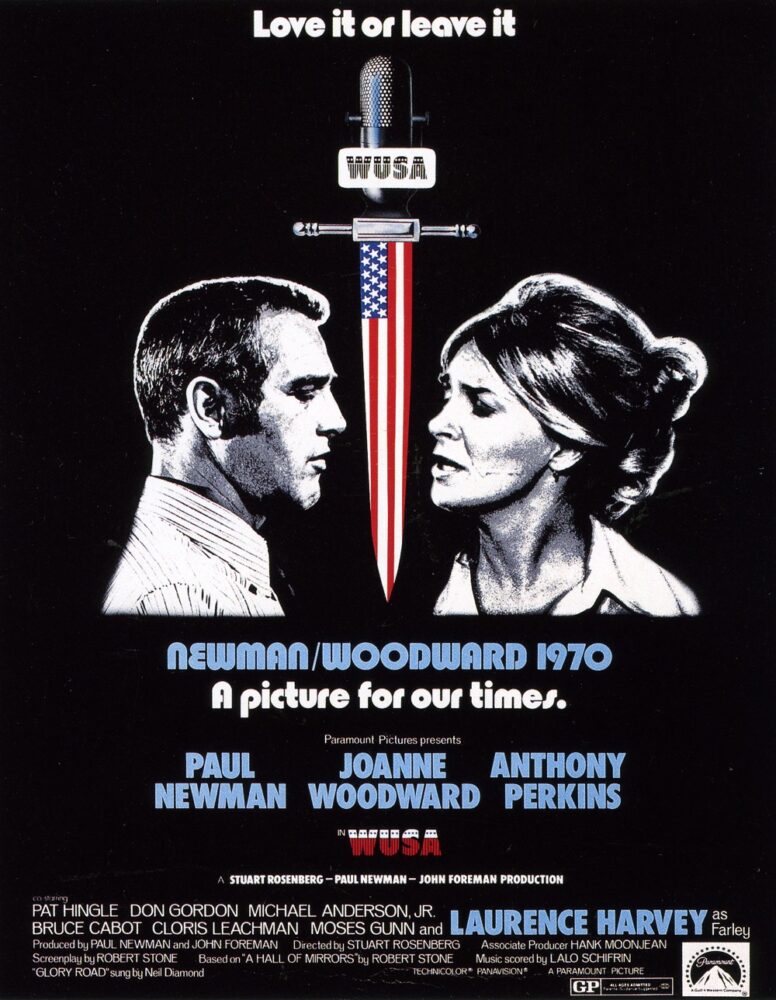

Alamy Images

In 1970, A Hall of Mirrors was adapted into the film WUSA.

At the dawn of this new decade, the Crescent City simmered with hope and fury, the promise of civil rights protests, and the omnipresent threat of reactionary violence. Somehow, someway, change would come to New Orleans.

The Stones would last less than a year in the city before returning to their native New York—long enough to witness the Black boycott of segregated businesses along the Dryades corridor and lunch-counter sit-ins at the Canal Street locations of Woolworth and McCrory’s, but just short of experiencing the white riots that accompanied the integration of two Lower Ninth Ward elementary schools in November.

Over the next half-dozen years, Stone transformed his short stint in New Orleans into one of the decade’s definitive novels, A Hall of Mirrors (1967), a book that exposed the nation’s ugly political, cultural, and racist underbelly like few others. “I had taken America as my subject,” he told an interviewer, “and all my quarrels with America went into it.”

The novel interweaves the lives of Rheinhardt and Geraldine, nihilistic drifters who land in New Orleans and quickly become lovers, not so much star-crossed as scar-crossed. He’s a talent-squandering, self-destructive “juicehead” with a taste for plonk. She barely survives as one of those lost souls who feel “blistered so thick that you’re tougher than anything they got and then the next minute you feel like you’ll die of the daylight if you can’t run and hide.”

Both having recently lost a partner and child, they find family in each other while laboring in a soap factory owned by Matthew Bingamon, a business tycoon–turned–media mogul who has recently launched a radical rightwing radio station: WUSA (slogan: “The Voice of an American’s America—The Truth Shall Make You Free”). Rheinhardt stumbles into the station’s studios and wins an audition for a position as a news announcer spouting race-baiting, anti-communist, fear-mongering agitprop.

Flush with ultraconservative blood money, Rheinhardt rents himself and Geraldine a French Quarter apartment—modeled after the Stones’ St. Philip Street address—downstairs from a dour do-gooder named Morgan Rainey, who knocks on doors in the city’s Black neighborhoods conducting welfare surveys for what he’s told is a private research company. (The Stones also worked as door-to-door canvassers in New Orleans for the US Census Bureau.) Rainey represents the idealistic, overeducated, white 1960s progressive, whose well-meaning yet naive search for meaning leads not toward salvation, but further disorientation. “I want to find out about humanness,” he confides in Geraldine. “What it is. Where mine is at and how I can keep it there when I find out.” He eventually discovers that his job’s ultimate outcome is to “rid the city welfare rolls of deadbeats, loafers, chiselers, freeloaders, harlots and commie sympathizers.” Bereft, he joins the city’s parade of the damaged and damned.

Rainey confronts Rheinhardt, who’s too bitter, drunk, and stoned to realize the role he plays in the culture skirmish that threatens to ignite into a full-blown race war. “I’m a liberal,” he asserts, earlier in the novel. “I don’t accommodate that rebop.” Nevertheless, Rheinhardt emcees WUSA’s coming-out party, a stadium-packed pageant advertised as a Restoration Rally and Patriotic Revival, where the night’s speakers preach of “rallying around the birthright their daddies bequeathed ’em,” attendees brazenly sport Nazi and Confederate regalia, and Bingamon distributes red, white, and blue ax handles for the head-bashings that are sure to follow the late-night cross burning.

A Hall of Mirrors is both a book born right on time—heralding George Wallace’s increasingly racist presidential campaigns and Richard Nixon’s winning “Southern Strategy”—and a half-century too early; it’s impossible to read Stone’s novel today without contemplating the horrors of the January 6 Capitol riot. (For a whole other trip, check out the novel’s film adaptation, starring the terribly miscast Paul Newman and his wife, Joanne Woodward. Despite what Stone thought—“it provided me with enough regrets to fuel one lifetime’s worth of insomnia,” he wrote in his memoirs—the film is well worth watching for its unparalleled images of late-sixties New Orleans.)

At the novel’s climax, Rheinhardt takes the stage to calm the bellicose crowd and delivers one of the most awful (and awfully believable) monologues ever put to print. Finally, the hall of mirrors that often is these United States fully reveals itself not as the carnival funhouse of our youth, but a grotesque and violent reflection of the American dream.

Rien Fertel recently wrapped up work on his next book, the story of Louisiana’s fraught and often ferocious relationship with its state bird, the brown pelican.