Foodways

Queen of Creole Cuisine

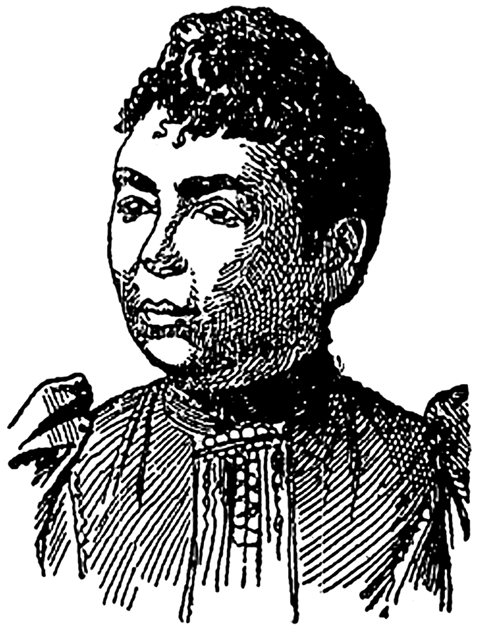

Nellie Murray was a celebrated chef in nineteenth-century New Orleans.

Published: March 1, 2017

Last Updated: March 11, 2021

Courtesy of Dillard University Ray Charles Program

Nellie Murray Standing in Front of Louisiana Mansion Club, 1894 Chicago's World's Fair by Maya Robinson.

This was the title of a featured article in the March 18, 1894, issue of the New Orleans Daily Picayune about a formerly enslaved woman of African descent who became the “Queen of New Orleans Creole cuisine.” Nellie Murray was the caterer for the “New Orleans Four Hundred,” the ultra-fashionable circle of aristocratic families. “Nellie is every inch a lady, as she could not but be when it is remembered that from her birth upwards she always associated with the elite of the city and the state,” the article declared. “All fashionable New Orleans knows how Nellie is always in demand for every elegant dejeuner a la fourchette, luncheon and swell dinner, and they know that when a ‘function’ of this kind is placed in her hands their guests will be served with such savory dishes as would make an epicure of Ancient Rome crown her with laurels.”

Twenty-nine years after slavery ended, Murray was hailed as “an aristocrat for all that her skin is dark.” Formerly enslaved and owned by the family of the fourteenth governor of Louisiana, Paul Octave Hébert, Murray was considered a “lady” in contrast to many of her race, who were seen as inferior and less than human. Murray’s opinion was valued as an expert and a chef. She was considered to have “great ability” and was beloved by wealthy elite French Creoles, Spanish Creoles, and Americans. Murray enjoyed an aristocratic lifestyle.

Murray lived in Paris for six months, Berlin for almost a year, Rome, Vienna, Bucharest, and other European cities. At the height of her career, She was offered a most honorable position as chef de cuisine at the Louisiana Mansion Club at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, where she became an instant celebrity. Northerners tasting Louisiana Creole cuisine for the first time waited for hours to meet her and relish her elegant menu. During the 1903 National American Woman Suffrage Association convention in New Orleans, Murray catered a private luncheon for Susan B. Anthony. Murray was also a patriot; she made 1,030 sandwiches with her famed drip coffee for American soldiers on their way to Cuba during the Spanish-American War.

Nellie Murray belonged to an endangered line of Louisiana Creole cuisinières, a matrilineal lineage of enslaved cooks who were the backbone of the traditional daily feasts, society balls, dances, and markets of French and Spanish Creoles dating back to the 1720s.The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book, published in 1901 and considered the bible of Creole cookery, praised these Creole cuisinières:

It must be remembered that many of the French settlers in La Louisiane were the aristocratic “emigres,” who brought with them the highest refinement of gastronomic culture while at the same time there came many peasants with their simple delicious “pot au feu” and “grillades.” Many of the cooks, indeed the vast majority of them in Louisiana, were negresses who had a share in the development of the Creole cookery. It seems as though colored folk had brought with them from the wilds of Africa certain knowledge, or instincts, regarding rare flavoring herbs. It was the negroes that went into the woods and brought forth the leaves and roots that, wisely prepared, added new half-tastes and quarter taste that, like the demi-teintes of the painter, add subtle attractiveness to the ensemble.

Much of the cookery we have described was invented at New Orleans, the metropolis of the Louisiana colony; but also a large part, as was suggested, was the product of cooks on the vast plantations that were almost like self-governing principalities scattered along the lakes, rivers and bayous of fair “Louisianne.

But what did these “negresses” bring with them to La Louisianne? What knowledge and instincts did they bring from the “wilds of Africa”? And was Creole cookery invented “at New Orleans” and on the “vast plantations,” or before New Orleans even existed?

Murray was formerly enslaved by Louisiana governor Paul Octave Hébert. Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection

When considering the history and legacy of Afro-Creole women of Louisiana in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, it is important to look at them through a new lens and to understand the historical significance and contributions they made to the development of Creole cuisine in La Louisianne. It is also important to look at the culinary history of West and Central Africa as a major influence on the culinary palate of Louisiana Creole cookery, since the majority of the cooking was performed by African Americans.

The marchandes (vendors), the tantes (mammies), and the old Creole cooks were descendants of highly skilled culinary geniuses from West and Central Africa, ancient civilizations with advanced knowledge in the culinary arts and agriculture.

During the transatlantic slave trade, Saint-Louis, Senegal, became a major port for the trading of slaves, crops, and goods. Saint-Louis was the first French settlement in Africa and was founded in the 1600s. During the French colonial rule of Louisiana, Saint-Louis became central to supplying colonial Louisiana with enslaved Africans. A total of 5,951 Africans from the Senegambian region were forced onto ships between 1719–1743. At these slave port cities, European traders had to eat foods that were foreign to them. Over a period of more than one hundred years from the arrival of the first French settlement to Senegal, the European traders had their first taste of Senegambian cuisine, which was prepared mostly by women. African women in cosmopolitan trade cities were the queens of the market, the cooks, the farmers, the traders, and the arbiters between African men and European men. Those who were chained, enslaved, and shipped to Louisiana came bearing gifts and expertise that no book could ever teach. West and Central Africa’s rich culinary traditions existed long before the first Arab and European traders arrived.

In an 1880 edition of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, the talent of the black cook was revered:

The Negroes are born cooks, as other less favored beings are born poets. The African . . . gradually evolved into an artist of the highest degree of excellence, and had from natural impulses and affinities, without any conscious analysis of principles, created an art of cooking for which he should deserve to be immortalized. And how is it possible to convey to the dyspeptic posterity of our ancestors, to a thin-blooded population whose stomach has been ruined by kitchen charlatans, sauce and gravy pretenders, kettle and pot druggists, any idea of the miracles of the old creole cooking? It was not an imitative; there was no traditionary lore about its origin; it had no ancestry; it sprang from itself.

But it didn’t “spring from itself.” It already existed and evolved from the hands of those who tended the crops, milled the rice, seasoned the stews, and larded the fish for centuries in Africa. Although oppressive colonial and slavery systems devalued and dehumanized women and men of African descent, the cultural memory, skills, and traditions survived and transcended. Such is the case of Nellie Murray.

By the time Murray died in 1918, she had gained legendary status worldwide, spoke out against New Orleans’ segregated streetcar laws, and amassed a fortune.

From a young age, Nellie watched her mother and grandmother, both enslaved cooks, masterfully prepare toothsome dishes for the family of Louisiana Governor Paul Octave Hébert and their esteemed guests at their Bayou Goula plantation. Murray learned from her mother and grandmother secrets of how to cook over an open fire, slowly cook daube with the perfect amount of spices and herbs, make the best drip coffee, and serve a feast fit for Versailles at a Louisiana governor’s table. The enslaved house servants decorated tables with the finest china and linen and slowly cooked and seasoned the freshest produce, seafood, and meats that the bayou had to offer. They served with precision and flawlessness. These childhood experiences instilled in Murray helped her to launch a lucrative catering business for an upper-class clientele post-Reconstruction.

Nellie learned not only from her mother and grandmother but also from New Orleans society women. By the time she moved to New Orleans to master her craft, she shared with The Daily Picayune that a Mrs. Thos. Miller mentored her. “I learned from that elegant lady, who entertained a great deal, exactly how things should be done, and all about arranging menus, decorating tables and serving nicely. I made a point to get all of the recipes I could. Many ladies, seeing my interest, were very kind to me and gave me recipes in which they excelled or were interested.”

It is unclear when exactly Murray moved to New Orleans or if she traveled to the city with the Hébert family. She is listed in the 1890 New Orleans Directory as living on Polymnia Street. The 1890s were a pivotal point in New Orleans history. The Civil War ended three decades prior, the city had recovered from a horrific yellow fever pandemic, and the election of both black and liberal white government officials during Reconstruction had emboldened segregationists committed to deterring any racial solidarity or upward mobility for African Americans. The city’s early tourist economy had expanded with the 1884 World’s Fair. The French language was becoming obsolete and seen as a hindrance by Americans, and in 1896, the Plessy v. Ferguson Supreme Court ruling institutionalized racism. In spite of these challenging times, Nellie Murray’s catering business was booming. Her clients were wealthy society women from New York to New Orleans. The prestigious Howards, Stauffers, and Whitneys were some of her New Orleans clientele. She treasured letters addressed to her, “Dear Nellie, make no arrangements, we want you.”

Courtesy of LSU Museum of Art

There were plenty of formerly enslaved cooks after the Civil War who cooked for elite families; what made Murray such a success, what set her apart from other caterers, was her persona as an aristocrat in spite of her race. There were none as eminent as Nellie Murray. In the March 18, 1894, Daily Picayune the journalist praised Murray’s success:

Nellie Murray is colored . . . But she has never associated with any but white people. And she picked only the aristocrats at that. So by association, Nellie became something of an aristocrat among her race. She deigned to notice few and associated with none. She was not educated in books but she was educated in experience and polished manners.

Do you know Nellie Murray? To admit that you do not is confession that you are not a member of the New Orleans Four Hundred.

All of the fashionable or nearly all of the fashionable functions given in New Orleans, are not considered complete without the assistance of Nellie Murray, whose deft fingers fashion many of the dainty dishes that delight both the eye and palate at dinners and luncheons during the gay season.

Nellie Murray, the famous New Orleans cook, is in the service of Miss Annie Howard, at her summer home, in Orange, N.J. and her delicious Creole dishes are becoming as renowned there as they are here. Nellie added not a little to the success of the numerous dinners, luncheons and teas last season in New Orleans.

Women of African descent were tremendous assets to the viability and growth of New Orleans for many reasons. Under the French and Spanish rule of Louisiana, the establishment of an educated, multilingual, business- and property-owning class of free people of color allowed for opportunities in entrepreneurship, a sense noblesse oblige and a commitment to social progress. Women of color outnumbered black men and white women in the eighteenth and nineteenth century, creating a system of cohabitación where European men entered into common-law marriages with women of color. These common-law marriages would create a generation of multi-racial children who were educated and in some instances were heirs to property and wealth. According to scholar Kimberly S. Hanger, “Women in general played a prominent role in town markets, but African-American women became perhaps the most influential buyers and sellers of food in New Orleans.”

By the time Murray died in 1918, she had gained legendary status worldwide, spoke out against New Orleans segregated street car laws, amassed a fortune, and paved the way for future women of color in New Orleans in the culinary arts, such as Lena Richard, the pioneering WDSU 1940s cooking-show host, and Leah Chase, chef and co-owner of the legendary Dooky Chase restaurant. Murray once remarked, “There is no place in the world that can compare with Louisiana in cooking, except Paris, and we can do just as well here as the cooks do there.”

Although caterers never leave behind physical buildings, Murray left a legacy of excellence that was bestowed to her from generations of African women and mastered in New Orleans society. During her European tour in the late 1800s, a New Orleans gentleman en passant told her, “Nellie, this is all very good but I have not yet eaten anything better than the old Creole cooks prepared in my kitchen in New Orleans. I would put you alongside a Parisian cook any day.”

In 2015, the Dillard University Ray Charles Program in African-American Material Culture launched its first academic conference, The Story of New Orleans Creole Cooking: The Black Hand in the Pot, which invited a host of scholars to share their research about the many unsung and unheard personas in culinary history. The conference, which was funded in part by a grant from the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, included the presentation of new research on Nellie Murray. In 2016, The Nellie Murray Feast, a Creole feast recreating some of her nineteenth century dishes, was launched in partnership with the Whitney Plantation, 2018Nola, and WLAE to raise the final funds for the production of the upcoming Leah Chase: Queen of Creole Cuisine documentary by Bess Carrick.

Nellie Murray defined herself against a segregated and often unjust background; her strength and tenacity to rise above low expectations for African Americans and for women is a true testament to her humanity. Over the course of her career she developed a world-famous cuisine that would bring all races and genders from across the globe to the table to break bread. Her persona as a grand Creole dame of New Orleans adds a certain panache to our history; this queen of New Orleans Creole cuisine deserves to be celebrated, admired and remembered forever.

Zella Palmer is Chair at the Dillard University Ray Charles Program in African-American Material Culture.