Winter 2024

Revolutionary Rhythms

"Baba" Luther Gray’s Sacred Activism and Music

Published: December 1, 2024

Last Updated: February 28, 2025

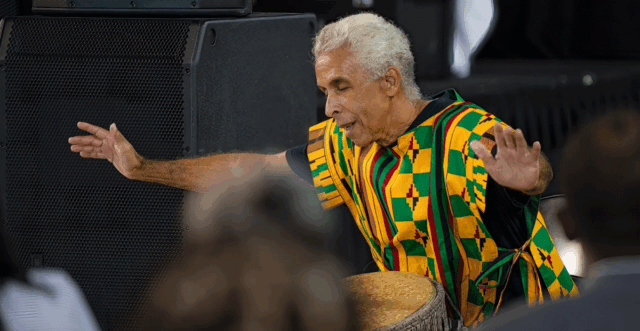

“Baba” Luther Gray participating in a second line.

Photo by Gason Ayisyin

The year 1994 was one of the bloodiest New Orleans had ever seen, with 424 homicides recorded—an average of at least one murder every day. The frequency of the killings and the sense of despair that had settled over the city prompted an unconventional response from local musician Luther Gray. A master African drummer, Gray organized a twenty-four-hour drumming marathon, a vigil he called “Drumming for Life,” coinciding with that year’s Congo Square International Festival, to acknowledge and commemorate those who’d been murdered in the city.

“Some of my family thought I was crazy,” Gray said in a recent phone interview reflecting on the event, which he’d led overnight—from noon on Friday, September 23, to noon on Saturday, September 24—in Congo Square. “I didn’t think about my life being in danger. I mean, we had police presence but more importantly, we had ancestral presence. I just believed that. Of course, my hands were hurting days after,” he said laughing. According to Gray and other participants who monitored the news, during the twenty-four hours the drummers drummed, nobody in New Orleans was murdered.

The idea that drumming could reduce violence in New Orleans struck some as laughable. Surely, drums were no match for guns and bullets, but for Luther Gray, it was the willingness of the community and its artists to unite for a necessary goal that gave him hope. He saw it as an opportunity for ancestral spirits to intervene.

“Baba” Luther Gray drumming in Congo Square in New Orleans. Photo by Gason Ayisyin

Okula Muhammad, who served in the New Orleans Police Department for eleven years, has a clear memory of the twenty-four-hour drumming marathon: “I remember that night because crime in the city was crazy then. I was on duty and heard the drums, and it was a weird feeling—because it felt safe. But it felt weird to feel safe at that time in the city, you know what I mean? Looking back, it was the spirit of our ancestors guiding and protecting us.” Today Muhammad is no longer a policeman. He left NOPD to focus on his wellness and family. He even drums on Sundays now with the Congo Square Preservation Society.

“Luther has always been willing to be intimate with the community,” Carol Bebelle, co-founder of the Ashé Cultural Arts Center, said. “He’s been able to calm rage in our young men and walk many through the stages of manhood. He welcomes the opportunity to do the heart work that is so needed in our community. His willingness to pull up a chair to whatever table has needs is a gift to us.”

Affectionately known as “Baba Luther,” Gray embodies the African word “Baba,” which means “father,” or an esteemed man of elder status who cares for you.

. . .during the twenty-four hours the drummers drummed, nobody in New Orleans was murdered.

Many New Orleanians have a Baba Luther story. They hear him drum in Congo Square every Sunday afternoon. Some have been mentored by him at Ashé. Some have encountered him through the drum processionals for remembrances, celebrations, and memorials he so often leads. And then there is his founding role with his beloved Bamboula 2000 performance ensemble, playing at local festivals. If you’ve seen Luther Gray in New Orleans, it’s likely you’ve seen him drumming.

Gray, a native of Chicago, credits his father, who played saxophone and clarinet, for his interest in music. With money saved from doing community errands, Gray bought his first drum—a conga—as an adolescent. It was an early investment that would eventually change the course of his life.

Luther Gray and his band Bamboula 2000 in Congo Square. Photo by Fernando Lopez

Chicago’s thriving drum culture was shaped by drummers who would often gather near Lake Michigan. A youthful Gray would watch and study their techniques and rhythms. Although he’s mostly self-taught, Gray credits fellow Chicago native “Master” Henry Gibson, a ’60s jazz and soul percussionist, session musician, and touring artist with Donny Hathaway and Curtis Mayfield, as his inspiration to take drumming seriously. By the time Gray graduated from high school, he knew drumming to be an art form.

After graduating from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he drummed with college friends and formed an R&B/funk band called Black Haze, Gray moved back to Chicago to be with his father until he died. Gray then took a job with the Illinois Phone Company.

But as fate would have it, one day, the company had no more jobs available in Chicago and was offering relocation opportunities. Without hesitation, Gray chose New Orleans. He’d get a chance to see Congo Square, a place he’d read about years prior, where enslaved people had danced and drummed on Sundays.

“It wasn’t a hard adjustment to go from the Midwest to the South at all,” he said about arriving in New Orleans in the early 1980s, “because I loved music, and the city was filled with it.” Gray continued working for the telephone company upon arriving in New Orleans for a few years. His telecommunication skills from the Midwest would transition into ancestral communications in the South. Drumming would eventually provide him with a new way of working and listening.

One day in the late ’80s, Gray met Carol Bebelle and Douglass Redd, artists leading after-school programming at St. Mark’s United Methodist Church. Gray was inspired by the duo’s creative energy. He wanted to add drumming to their youth programming, and they agreed. This intersection would set them on a journey of friendship and cultivation. On the horizon was the Ashé Cultural Arts Center, which Bebelle and Redd would open on Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard in December 1998.

“We did a lot of things by instinct then that eventually became realities,” Gray said. We just believed in what we were doing and knew the universe would reward our dreams.”

“Baba” Luther Gray.

Luther Gray considers himself “a cultural warrior.” In 1984 he initiated the Congo Square Drum Circle, and in 1989 he co-founded the Congo Square Foundation (now known as the Congo Square Preservation Society), both of which worked to restore Sunday drumming in the historic square and integrate it into the community. He co-chaired the New Orleans Committee to Erect Historical Markers on the Slave Trade in Louisiana with Freddi Williams Evans for the New Orleans tricentennial celebration in 2018. Bamboula 2000, the musical collective he founded in 1994, is grounded in cultural entertainment that teach lessons about enslaved people and uplift the sounds of the diaspora through their lyrics. In their song “The Wild Bamboulas,” Baba Luther sings the lead:

We come out of Congo Square

On any Sunday you’ll find us there

We got the drum

We got the dance

Can put you in a healing trance

The call us wild because we’re free

They say we’re strong and know our history

Now seventy-two years old, Baba Luther still remains committed to Congo Square—on Sundays, you can find him there unloading his drums from his vehicle for people to play—although he admits to taking some breaks and letting the younger drummers lead at times. His favorite rhythm to play is the Bamboula beat, believed to have originated in the Congo. Gray hears the New Orleans second-line beat at the core; he emphasizes that African and New Orleans rhythms are intertwined.

Baba Luther believes the future of Congo Square is in good hands. The younger drummers he has mentored have been dedicated to showing up at Congo Square on Sundays. Kalamu ya Salaam, who describes Gray as a master teacher/student, said Gray “has taught us to value and respect Congo Square by his consistency. He taught us that what you love, you devote your being to it.”

Across the centuries, Gray estimates that at least a million people have drummed or danced in Congo Square. “It’s amazing when you think about it,” he said. “Drumming has connected me to people from all over the city and world. It has helped me discover and live my purpose.” Everywhere Baba Luther drums becomes a living classroom.

“When people come to Congo Square, I tell them to put their right hand over the left part of their chest and feel the heartbeat,” Gray said. “If they can feel their heartbeat, then they can drum. Drumming is heartbeat.”

Kelly Harris-DeBerry is a poet and the author of Freedom Knows My Name. Read and listen to more of her work at kellyhd.com.