River Harvest

Hoop net fishing in Avoyelles Parish

Published: September 1, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

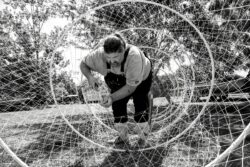

Rusty Kimble fashions a new hoop net in his front yard in Simmesport.

“Simmesport was built on the back of a buffalo fish,” said Kimble, a lifelong hoop net fisherman who captained his first boat, at age fourteen, in 1983. Since then, he has witnessed the slow demise of an industry. In the mid-1990s, Simmesport claimed eight fish markets. Two remain. Clyde Dufour and his wife, Debra, run Highway 1 Fish Market. In 2005, fifteen fishermen made regular deliveries. “I’ve lost over half my fishermen since then,” Dufour said.

“They either died, or they got starved out and quit,” Kimble said. “It’s at the end.”

Deborah Guillot Veade remembers Simmesport’s thriving hoop net industry of the 1950s and ’60s. “My grandfather lived to be almost 102 years old, and he always claimed it was because he ate more fish than meat,” she said. Like Kimble, he made his own nets. “He and my uncle would sit on their back porch and knit those nets faster than a woman could knit a sweater.”

Once made of fiberglass, most hoops are now made of PVC pipe. The widest are five, six, or seven feet in diameter. One net threaded through nine hoops can span seventeen feet. A sturdy net will last twenty years, said Kimble, who uses a knitting needle to mend torn nets aboard his boat, his hands as fluid as those of a symphony conductor despite waves from passing barges.

Simmesport lies southwest of the Old River Control Structure, where the Army Corps of Engineers maintains the distribution of flow between the Mississippi and Atchafalaya Rivers and, crucially for South Louisiana, prevents them—soulmates in the cosmos of waterways—from merging. Add to this landscape the Red, which flows into the Atchafalaya, and Old River (Upper and Lower). Witness a place where water shapes identity.

“The river is part of my soul,” said lifelong commercial hoop net fisherman Donnie Dibble Jr. “I think I have Atchafalaya water running through my veins. I love being out there and feeling close to my heritage and knowing that my grandparents and their grandparents depended on this river for their livelihood. The river keeps me grounded, it gives me a purpose I can be proud of.”

The northernmost parish in Acadiana, Avoyelles is a place in-between, Louisiana’s crossroads in parlance and temperament. To Kimble, “There ain’t no better spot in the world.” He listened to Dufour tally the day’s haul. The numbers were low: 525 pounds of buffalo, 508 pounds of gou, 387 pounds of catfish. “That should be two thousand pounds each at this time of year,” Dufour said.

Despite this, any other life seems unfathomable. “Tell me,” Kimble said, “can you get great boudin or cracklins in a gas station in New Orleans? No. Why would anyone live anywhere else?”

Kevin Rabalais’s writing and photographs have appeared in newspapers and magazines in Argentina, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States. An Avoyelles Parish native, he is the author of a novel, The Landscape of Desire, and teaches in the Department of English at Loyola University New Orleans.