Safe Haven

Reflections on Louisiana Green Book sites

Published: May 31, 2022

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

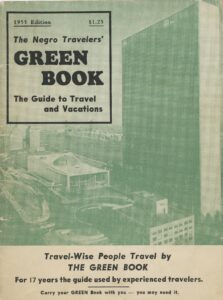

The Historic New Orleans Collection

A 1955 Green Book.

The Green Book, as it came to be called, was the creation of Victor Green, a Black postal worker living in Harlem. In 1936, automobiles become an affordable, luxurious alternative to public transportation, and Black Americans were cashing in. Autos made travel easy, but there were still obstacles for the Black traveler. Identifying where to eat, where to stay, and even where to fill up your tank could carry life-or-death consequences.

Helping Black people identify these “safe havens” in the late ’30s was the purpose of Victor Green’s booklet, and Louisiana was full of options, as it was home to several blossoming Black commercial districts during the Green Book’s heyday. For Safe Haven: Louisiana’s Green Book, a digital-first series from Louisiana Public Broadcasting, I teamed up with co-producer Emma Reid and began scouring the state to pinpoint ten locations listed in the Green Book.

What we discovered was sobering. After a strong and promising start, I realized many of these once prominent Black-owned businesses were ghosts. Of the ten locations we visited, only one was still operating. Everything else was just a memory in someone’s head.

Almost every Louisiana site listed in the Green Book had been destroyed by progress.

Giron’s Tourist House

I arrived in Opelousas on a hot and muggy Sunday, looking for the man I was supposed to interview through a rain-covered windshield in the parking lot of one of Opelousas’s oldest Black Catholic churches. Growing up in Baton Rouge, I never visited Opelousas—it always seemed like a distant town, even though it was only an hour away. Opelousas, home to only 16,234 people, is a quiet and rural, but the community was once home to a vibrant nightlife scene. The great music legends of the Motown era passed through here performing for audiences—Black and white. Of course, for these musicians finding lodging wasn’t as easy as booking a gig. At the height of the Jim Crow era, Black musicians, regardless of their fame, could not sleep in white spaces. They had to find Black-owned hotels or residences where they could safely spend the night, which could be challenging in rural places like Opelousas.

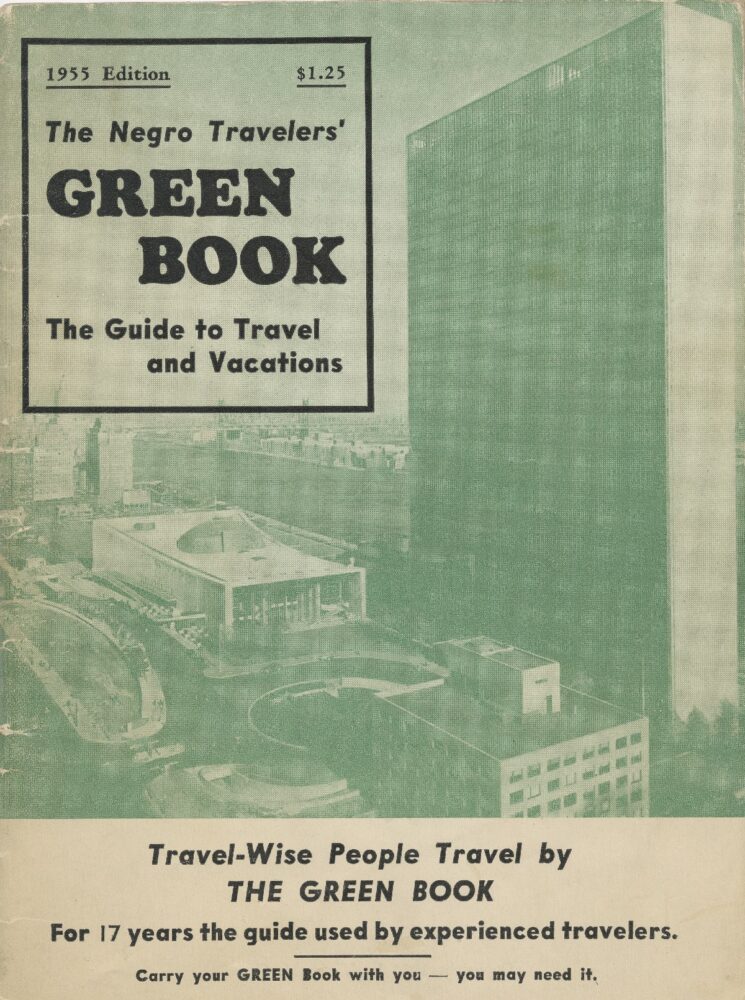

Louisiana listings in the 1955 Green Book. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

While I was imagining how that would make me feel, a small man with glasses parked his car next to mine. He rolled down his window and waved. “I’m Wilbert Giron,” he said.

Giron, who was in his eighties, told me he liked to be called “Sub.” Sub was born and raised in the city and immersed in rural nightlife. When hotels wouldn’t take in Black artists or clients, his grandmother Buelah Giron did. Her home on Lombard Street had six bedrooms, which she offered as boarding rooms. Her home would be listed as a guest house in the Green Book from 1937 to the last edition, published in 1967. “There were people there all the time. Twenty-four-seven,” Sub said.

Buelah’s door was open to anyone who needed a place to stay. Musicians were only a small portion of the visitors who came through the front doors. Sub’s grandmother housed all travelers, including Black teachers who came to Opelousas to teach at one of the only Black schools in the city. “You had teachers live there, students. Construction workers, bricklayers. You know, she just took everybody in.”

When Sub was telling me about his grandmother’s home, I was expecting a story that would hurt—one that focused on the pain of segregation. But the stories he told were about food and friendship. About men playing cards in the kitchen over hot plates of blood boudin. About musicians that played his grandmother’s piano into the night. Despite all the pain that existed in this world and in Opelousas, his grandmother’s house was a respite from all of that. Memories of the liveliness that filled her home occupy more space in Sub’s mind than any bigoted incident ever could.

My own family members won’t speak about any aspect of their lives before the Civil Rights Movement. It’s a taboo topic for a variety of reasons. To hear Sub talk reminded me that even though times were bad, Black people still experienced joy in the face of discrimination. In a way, the Green Book offered an escape and an opportunity for happiness.

The Dew Drop Inn

The Dew Drop Inn looked nothing like I’d imagined. The front of the building was torn apart, exposing wooden frames and the burgundy, cracked exterior of the original building. The nightclub’s sign was faded and stained. The doors were locked with thick chains intertwined in the iron door frames. To me, it was a hollowed-out version of the stories I’d heard. Seeing the club after fifty years of inactivity, I found it hard to visualize the wild, passionate crowd of people who frequented this place in its prime.The most inviting aspect of the building was the man standing in front of it. Kenneth Jackson was over six feet tall with thin glasses framing his eyes. The moment I stepped out of my car, he introduced himself as the former owner of the Dew Drop Inn.

“This actually was a pre-school for me.” He looked at the building with pride. Those walls contained Jackson’s entire childhood.

“My grandmother came down here every day. So when she came to do her shift, we would ride with her,” Jackson said. “While she was doing her workaround, we’d be in a bar playing with the different little instruments on the stage. We’d be going behind the bar and eating the cherries and the orange slices and stuff.”

His grandfather, Frank Painia, had scraped together money from years of cutting hair and good networking skills to create the Dew Drop Inn. It started as a barbershop that sold refreshments on the side of LaSalle Street in 1939. The business ballooned into an all-in-one barbershop, nightclub, restaurant, and hotel, and its popularity spread quickly among America’s Black elite. The Dew Drop transformed into a hub for off-color entertainment as well as celebrity appearances from the likes of Etta James, James Brown, and Ray Charles.

But when I listened to Kenneth Jackson explain the significance of the family business, I learned that it served as more of a refuge than an entertainment spot. When the club opened in the late ’30s, racial tension gripped the city of New Orleans. The blue walls of the Dew Drop acted as a buffer against the harsh realities of the time. Jackson’s grandfather purposely challenged social taboos, inviting the LGBTQ community to patronize the club as well as to perform. One of the club’s most popular performers was a cross-dresser who used the stage name Wild Cherry. She donned black wigs, lipstick, dresses, and high heels to perform raunchy comedy acts and slow serenades.

Painia also broke the racial barrier on more than one occasion. “My grandfather got in big trouble,” Jackson said. “He actually went to jail, because he would allow white people to come into the hotel, come in at the bar or restaurant, no problem. I had no idea as a kid that it was against the law for white people to be in here.”

But like almost every other location listed in the Green Book, this safe haven was temporary. The club fell on hard times following integration. No amount of renovations could attract business, and the club closed in the late ’60s. But the image of the Dew Drop Inn will be forever ingrained in New Orleans’s history, immortalized in music, art, and Jackson’s memory.

The Ever-Ready Hotel, ca. 1938. Joan Forbes.

The Ever-Ready

At the Ever-Ready Hotel, there weren’t even remnants of the building to explore—only the black and burgundy floor tiles, pasted atop crumbling cement. I stood in the center of the ruin and tried to imagine what it had looked like.I couldn’t.

Unlike the Dew Drop Inn, there weren’t many sources of information about one of Baton Rouge’s first Black hotels. Everything I learned about the business came from the descriptions inside the Green Book and the memories of Joan Forbes, niece of Joseph Henderson, the hotel’s owner.

“I would go visit Ever-Ready’s cafe and cab stand when I was little. I was a little five-year-old sitting on the bar,” Forbes said. “So I got to see everybody come in.”

Forbes, who recently passed away at the age of seventy-six, was born during the Ever-Ready’s peak and lived in Baton Rouge all her life. I visited her house, where she kept records of hotel visitors and pictures of her family. When I arrived she had a group of friends waiting to talk to me along with everything laid out in manila folders on her kitchen table.

“The whole block was like little Harlem, you would call it a little Harlem because it was all Black,” Forbes explained. “Everybody was friends.”

She pulled out a copied photograph of the hotel. It was heavily pixelated, but you could make out almost every detail of the building. The Ever-Ready’s story, Forbes said, started in St. Francisville, where her family was from; they lived as preachers and domestic workers in old slave cabins during the 1930s. But St. Francisville was a Ku Klux Klan stronghold, buckling under the weight of racial violence, and Forbes’s ancestors lived in a near-constant state of fear—of a torch thrown through their windows, or awakening to the fiery blaze of a cross burning in the front yard. The family moved thirty miles south to Baton Rouge, where they could start over in the center of a Black commercial district, something they hadn’t seen before.

Forbes’s uncle, Joseph “Everready” Henderson, and his siblings accumulated enough money to build a hotel on Government Street. The Ever-Ready was a white, boxy, two-story building on the street’s edge. It started as a simple place for lodging, but quickly expanded into a photography studio, cab stand, and bar. It attracted gospel artists and celebrities. Although white people couldn’t stay there, Forbes said the racial barrier didn’t stop them from visiting.

“Bette Davis and all of them would come down—they really liked soul food,” Forbes said. “So they would stop by and get some ribs and mustard greens and cornbread.”

I learned from this project that convenience was key for America’s golden generation. If you could find a way to combine multiple businesses in one, you were on your way to creating a local empire. That’s what the Ever-Ready was for Baton Rouge’s Black community. Like almost every location in the Green Book, this hotel’s significance transcended its original purpose. Henderson wanted Black communities to be self-sustaining. He gave out money and loans to other Black entrepreneurs and helped launch several businesses. A lot of his siblings moved away from Louisiana with the skills they acquired from the Ever-Ready and opened other businesses that appeared in the Green Book.By the late ’60s, Henderson’s family had amassed a sizeable income from the hotel business, and they’d developed refined tastes. Forbes said that almost every family member drove a Cadillac, and that it was the norm among the family to buy one when the latest model was released. When Henderson tried to buy a Cadillac from a white dealer, the car salesman questioned him. “He asked him, ‘how can you afford to buy this?’” Forbes said.

In a sense, wealth had advanced the Hendersons closer to whiteness, but it still couldn’t erase the white supremacy that was so deeply ingrained in Louisiana’s cultural norms. It was exhausting even to Mr. Everready himself. Henderson and his family had escaped burning crosses and a life of servitude just for another white man—a car salesman—to demean him. He sold the Ever-Ready Hotel, packed up his family, and moved to Oakland, California. Business declined after he left, which Forbes attributed both to poor management and integration. The Ever-Ready closed in 1969, and the building was eventually demolished, flattened to the floor tiles I stood on while researching the hotel.

“The whites couldn’t believe, basically, that Blacks had that kind of money,” Forbes said, “and they resented it in a way, and would rather see the buildings destroyed than to see them remain. And that’s what happened. They are being torn down. It is like they were never here in the first place.”

It was heartbreaking for Forbes—not because the building was gone, but because most people don’t know it was ever there in the first place. She tried to ask the East Baton Rouge Parish Metropolitan Council to put up a sign in front of the building’s foundation, but she didn’t garner enough support.

“Everybody needs to know about it,” Forbes said of the Ever-Ready. “Everybody, I don’t care what color you are. Wherever you came from—rainbow colors. They need to know all this existed.”

More Louisiana listings in the 1955 Green Book. The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Carrie’s and Poro’s Beauty Schools

When I finished interviewing Forbes, I noticed two things: her copy of the Green Book had several places highlighted, and her folder was filled with pictures of other businesses outlined in the Green Book—ones that I had been unsuccessfully trying to locate for months. One wrinkled, age-stained flier looked as if it had been ripped from a booklet. There was a Black woman on the cover wearing a white dress. “That’s Miss Carrie,” Forbes said.Carrie Taylor was a Black hairstylist who owned Carrie’s Beauty School in Baton Rouge. Listed in the Green Book from 1940 to 1955, her business was located down the street from the Ever-Ready Hotel, and Forbes’s family was connected with hers. One of the women Forbes invited to our interview, Mada McDonald, was a family friend of Taylor’s.

McDonald’s grandmother, Mada Porter-Edwards—nicknamed “Mother Mada”—opened Poro’s Beauty School in New Orleans in 1939. Before it appeared in the Green Book in 1947, Porter-Edwards struggled to get her license. “Louisiana Board of Examiners did not want her to have her cosmetology license,” McDonald said. “I think that they just did not want to see her grow in that industry. But she was die-hard—to say, ‘I’m gonna get my cosmetology license. I am trained to do this.’”

Women came from all over the city to get their hair done (and buy purses) at Porter-Edward’s salon. But more importantly, they came to learn. Her school taught women how to accentuate Black beauty and build businesses in the process. In the late ’30s and early ’40s, Black women usually found work as maids and cooks. Poro’s gave them the ability to expand their options.

Porter-Edwards worked alongside Taylor, as a matron of ceremonies for Carrie’s Beauty School, in Baton Rouge. From 1939 to the late ’60s, both Taylor and Porter-Edwards brought forth a new class of Black women: business owners who could also help sustain communities of color.

Carrie’s and Poro’s disappeared from the Green Book in 1955. By then, Porter-Edwards and Taylor had reached retirement age. There wasn’t anyone to take over the businesses, and both salons closed down.

I’ll never stop at another convenience store for a quick cup of coffee again without remembering the lessons I learned while working on the Safe Haven series. My history is full of people with determination and perseverance. They were comfortable in their Blackness, even while much of the world tried to discourage it.

In school, I learned about one man’s dream. I learned about a man who invented peanut butter. But the stories of great vision and community-building that come from my home were buried. I feel lucky to have learned them for myself and grateful for the chance to share them. Now we all have the opportunity to understand our collective history—and hopefully one another—a little better.

Kara St. Cyr is a reporter for LPB’s Louisiana: The State We’re In. She is a Baton Rouge native who graduated from LSU with a degree in mass communication in 2018 and worked as a reporter at WVLA NBC Local 33 prior to joining Louisiana Public Broadcasting. She has co-produced the documentary, Louisiana’s Black Church: The Politics of Perseverance and the mini-doc series, Safe Haven: Louisiana’s Green Book.

To learn more about Louisiana sites listed in the Green Book check out the Louisiana Public Broadcasting series Safe Haven: Louisiana’s Green Book. The eleven Safe Haven episodes, shot and co-written by Emma Reid and Kara St. Cyr, feature Black-owned service stations, hotels and tourist homes, beauty shops, nightclubs, and more. Episodes available online at lpb.org/greenbook.