Sailing While Black

The story of free black sailors trapped in Louisiana’s slave prisons

Published: March 1, 2020

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

The Historic New Orleans Collection

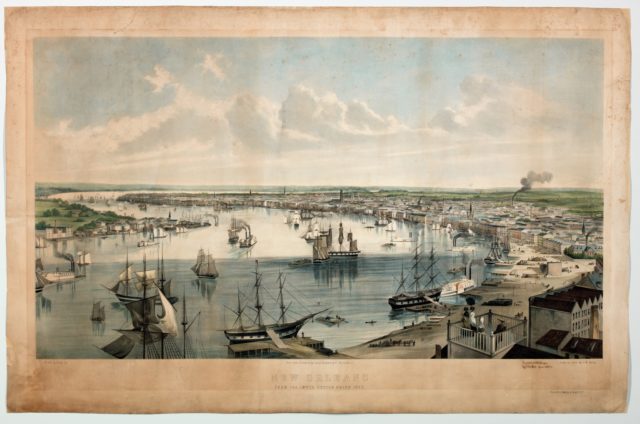

New Orleans from the Lower Cotton Press 1852 by J. W. Hill.

When Augustus Smith entered New Orleans’s Second Municipality slave prison—situated where the Mercedes-Benz Superdome stands now—he met, among the enslaved prisoners, scores of other free black seamen from port cities scattered throughout the world: New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Annapolis, Havana, Nassau, Kingston, Veracruz, Liverpool, Le Havre, and even Bombay. Some had been held for months, none had been convicted of a crime, all were held as captured runaway slaves. As persons presumed enslaved, they had no right to trial, no ability to sue for their release, and no means of contacting family or friends. None knew when—or even if—they would ever be set free.

In April 1841, Augustus Smith joined five other sailors in smuggling a letter from the slave prison. The seamen vowed to resist their captivity, writing that as “men that have been suckled with that sweet milk of Liberty and freedom,” they would rather “Lay ourself Down and die like men” than continue to suffer such “arbitrayrie power on us.” They also expressed confusion: why, they wondered, did Louisiana officials seem so “afraid to have us put at Liberty?”

Free black sailors terrified public authorities in slave societies, who feared that these versatile and highly mobile men of color would disseminate revolutionary ideologies, inspire slave rebellions, and quarter fugitive slaves who sought to escape to freedom. Black sailors were “the worst evil that threatens the peace of the South,” the New Orleans Commercial Bulletin proclaimed in 1841: a people “most dangerous to our institutions,” committed to “carrying on the work of insurrection and massacre.”

Augustus Smith’s own life story, dictated from within the prison, helps illuminate the threat that free black sailors posed to a society committed to black subjugation. Though employed aboard a Boston-based ship, Smith had been born in Angostura, a small riverport town deep inside the Venezuelan heartland, sometime around the dawn of the nineteenth century. He was probably still a child in 1817 when Simón Bolívar, the famed South American liberator, conquered Angostura and used the city as the base from which to wage guerilla warfare against the Spanish Empire. In 1819, Bolívar delivered his “Angostura Address,” formally proclaiming his revolution’s opposition to slavery, racial caste, and colonialism. One imagines young Augustus’s excitement at the revolutionary events unfolding at his doorstep.

By 1830 Smith had found work as a sailor, visiting New Orleans for the first time aboard the Baltimore-based schooner Dutch Chest. In the early nineteenth century, free blacks accounted for roughly one-fifth of all sailors employed on American ships. Seafaring was one of the most profitable entry-level jobs available to free blacks, whose race excluded them from most opportunities for vocational training and professional advancement. In addition to steady wages, seafaring offered rare opportunity for international travel, adventure, and the forging of a sense of transnational black identity through interactions with Afro-descendent communities scattered throughout the Americas.

Slaveholders perceived that black mariners like Smith exemplified the possibilities of black liberation and conveyed radical ideologies that “infected” the minds of enslaved Louisianans. As Augustus Smith’s own life story illustrates, these fears were not entirely unfounded: this was an exceptionally well-traveled young man who had personally witnessed antislavery and anticolonial revolution.

Beginning with South Carolina in 1822, southern states passed draconian laws, called Negro Seamen Acts, which mandated the incarceration of all free black sailors while their ships were docked in port. By the 1840s, according to one contemporary estimate, Charleston, Savannah, and Mobile each jailed more than two hundred free black sailors each year. Louisiana adopted a different approach: here, police arrested free black sailors on the pretense that they were fugitive slaves, imprisoning them in slave prisons until captains paid hefty jail fees and removed them from the state. Sailors whose captains failed to retrieve them, like Augustus Smith, remained incarcerated indefinitely.

Most of these sailors were arrested in downtown New Orleans, after their accent, clothing, or mannerisms betrayed that they were from out–of-state. To protect against the constant danger of wrongful arrest and kidnapping, antebellum free black travelers typically carried legal documentation showing that they were free, known as “freedom papers.” Yet New Orleans police ignored this legal documentation in arrests involving out-of-state sailors, who could only watch in terror as their freedom papers were systematically discarded or destroyed. Robert Barbadoes, a sailor from New York City who would spend five months in a New Orleans slave prison, was aghast as his papers were “taken from him, and torn up.” Rufus Kinsman, a native of Connecticut who would spend an entire year in a slave prison, was told that his papers had been invalidated because they lacked the seal of the Connecticut governor. When Connecticut Governor William Ellsworth personally intervened by transmitting new freedom papers, New Orleans still refused to release Kinsman, insisting that the city held another man—Kinsman’s original arrest record listed his name as “Rufus Parsman.” Amid this ordeal, Kinsman described New Orleans as containing “the worst of prisons and people that this world can produce.”

Kinsman’s characterization of New Orleans’s slave prisons was probably not a gross exaggeration: these institutions combined the worst brutalities of antebellum prisons and antebellum chattel slavery. Upon their imprisonment, sailors were subjected to the standard punishment prescribed for captured fugitive slaves: sailors were stripped nude, strapped to the prison whipping rack, and given twenty lashes, all in full view of dozens of other inmates.

This lithograph by Felix de Beaupoil, titled Vue d’une rue du Faubourg Ste. Marie, Nelle. Orléans, shows penal laborers matching written descriptions of New Orleans’s enslaved labor force that would have included impressed sailors.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

Each day, roughly one hundred prisoners were shackled into chain gangs for labor on New Orleans’s public works. Though largely forgotten today, New Orleans’s slave chain gangs were integral to the growth of the Crescent City. Indeed, it would have been virtually impossible, prior to the Civil War, to find a single city street, park, or pipe that had not been built, repaired, and cleaned by slave (and sailor) penal labor. Every day, slave chain gangs collected the city’s trash, graded and paved the city’s streets, swept sidewalks, planted trees, cleaned public parks, scrubbed marketplace stalls, unblocked sewage lines, strengthened levees, rebuilt and repaired wharves, removed dead pack animals, operated the city’s public ambulance service, and interred paupers at the city’s potter’s field. In short, they were the city’s main sanitation, custodial, and construction force.

The experience left profound physical and emotional scars on both sailors and slaves. John Callis, a sailor shackled to his wife Charlotte (a ship’s cook), recollected that the combination of overwork and hunger reduced them “to mere skeletons.” John H. Slate, a Connecticut native imprisoned for four years and six months, revealed that the chain gang’s shackles had chafed his ankle down to the bone. After a period ranging anywhere from days to years, sailors were unceremoniously handed over to ship captains short on crewmen, on condition that the captains pay their outstanding jail fees and remove the seamen from the state. Captains often docked these jail fees from sailors’ future wages.

Black sailors spread word of these atrocities throughout the maritime world. New Orleans’s prisons were “famous” among sailors, one former mariner reported in 1835. As word spread, free black sailors went to great lengths to avoid New Orleans, and other southern ports where Negro Seamen Acts were enforced. En route to New Orleans, black sailors mutinied, struck, jumped ship, or demanded that their captains vow to cover their jail fees and obtain their immediate release. Yet this was the age of cotton; by 1840, New Orleans was the fourth busiest port in the world—the city was virtually impossible for a sailor to avoid. Indeed, many sailors, like Augustus Smith, reported that they had been incarcerated in New Orleans’s slave prisons numerous times.

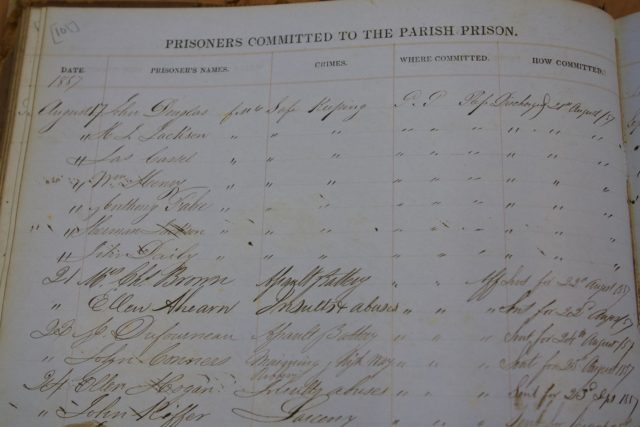

Free men of color, designated with the abbreviation “fmc” and including visiting sailors, were held for “safe keeping” in the parish prison following the 1842 law. City Archives, Louisiana Division / New Orleans Public Library

In 1842, the Louisiana Legislature restructured state procedures for incarcerating free black sailors with the passage of “An Act more effectually to prevent free persons of color from entering into this state.” This new law acknowledged that free black sailors were free, requiring their incarceration in Orleans Parish Prison—not municipal slave prisons—while their ships were docked in port. The new law also prohibited all free blacks born out-of-state from residing in Louisiana, unless they had moved to Louisiana before 1825 and had formally registered their residency. Non-native free blacks who did not meet these residency requirements, and who failed to emigrate, were to be sentenced to hard labor in the state penitentiary for five years. Any formerly incarcerated illegal resident who still failed to emigrate, or who subsequently reentered Louisiana, was to receive a life sentence.

Free black immigrants faced a terrible choice: flee Louisiana forever, or risk imprisonment and impressment. Many chose to leave. Scores remained and were arrested.

Despite all that he had endured, Augustus Smith resolved to stay. Smith had decided to settle down in New Orleans after his third release from the slave prison. Defiantly, and like so many immigrants before and since, he chose to make the city his permanent home.

We know this because in March 1845, Augustus Smith was arrested yet again—this time, as a free black illegal resident, living in New Orleans in violation of the 1842 law. He pled not guilty. Remarkably, he was acquitted.

Yet New Orleans police remained committed to Augustus Smith’s expulsion or captivity. This Afro-Venezuelan man of the world simply seemed too dangerous to be allowed to live free. One year later, in March 1846, Smith was rearrested for the same crime. He assembled the money to hire a lawyer, who entered a plea of “autrefois acquit”—previously acquitted for the same offence. Once again, Smith was released.

Two months later, Smith’s luck ran out: shortly after midnight on June 3, 1846, police arrested him again—this time, as a fugitive slave. He was admitted to the Third Municipality slave prison.

Smith was promptly released—only to be arrested yet again as an illegal resident, in May 1848. Once again, Smith beat the charge. His lawyer argued that Augustus Smith was no longer some itinerant sailor: rather, he should be considered “a Citizen of the State of Louisiana, and not in the State in contravention of the Law.”

Augustus Smith’s decade-long battle against summary imprisonment in Louisiana is remarkable. Between 1836 and 1848, this traveler from Angostura was incarcerated in New Orleans eight times—four times as a fugitive slave, and four times as a free black resident alien. Miraculously, he persevered through whipping rack, chain gang, and expulsion hearing, suggesting extraordinary determination to plot his own life trajectory. Smith’s story underscores the daily challenges faced by free blacks as they struggled to secure freedom and belonging in a society committed to black captivity and subjugation. Two centuries ago, Louisiana’s prisons were epicenters of these struggles: places where the boundaries between citizenship and exclusion, freedom and confinement, prison labor and slave labor, became contested and blurred.

John Bardes is a PhD candidate in history at Tulane University. His scholarship explores policing and incarceration in the context of slavery and emancipation, and has appeared in American Quarterly, Journal of Southern History, and Southern Cultures. He may be reached at [email protected].