Fall 2024

Salt of the Earth

In Winn Parish, an ancient salt dome has sustained life for centuries

Published: September 1, 2024

Last Updated: December 1, 2024

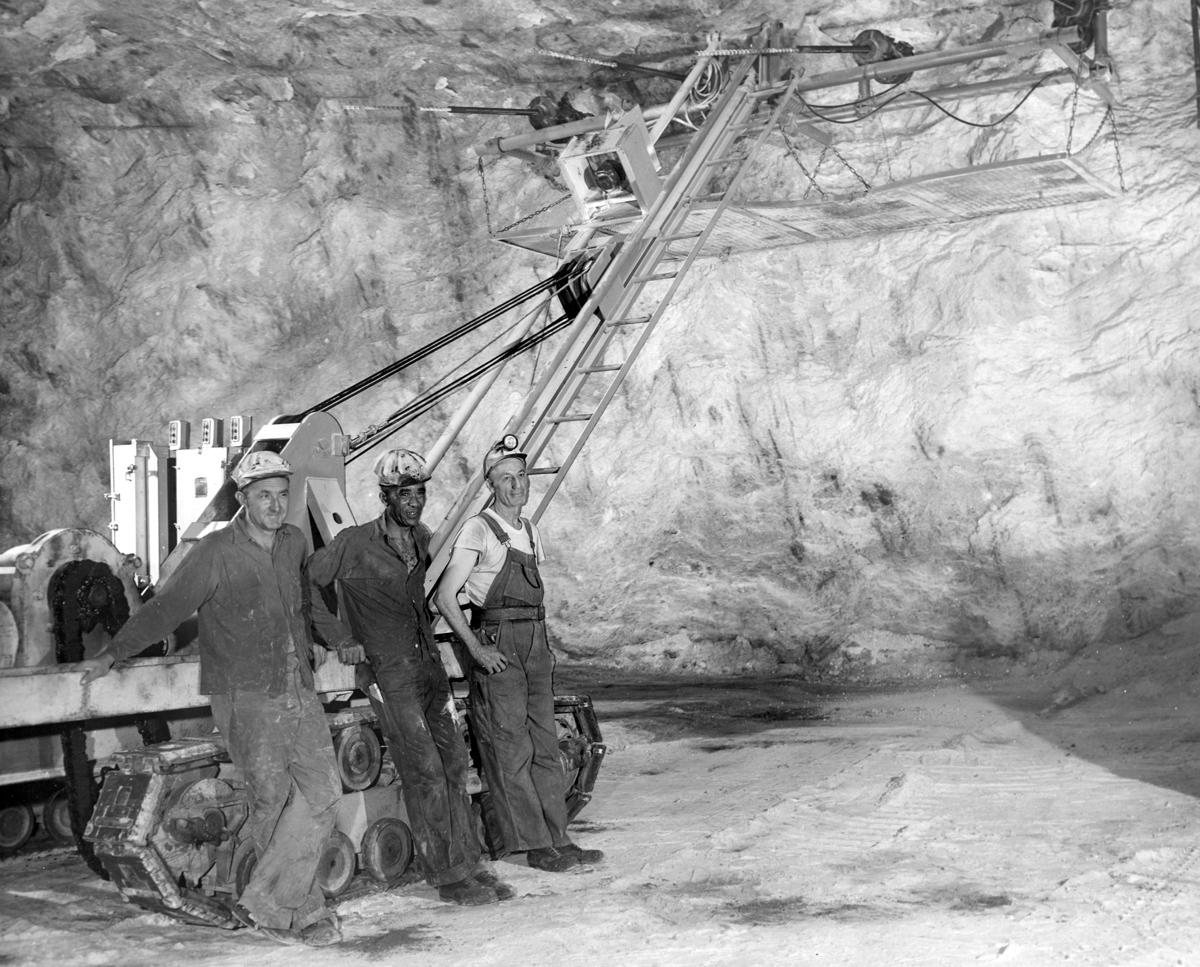

State Library of Louisiana

Three workers taking a break inside Carey Salt Co., another salt mine in Winn Parish in the 1940s.

Wild animals came first to lick the barren patches of earth along a small bayou in today’s Winn Parish, Louisiana. In time, humans followed their paths to the area to gather a chemical compound vital to the well-being of all animal life—salt. As the main source of sodium and chloride in the diets of mammals and birds, salt plays a critical role in regulating blood pressure, blood pH, and fluid levels; it is essential for proper muscle and nerve function. Now the site is known as Drake’s Salt Lick or Drake’s Salt Works for Reuben Drake, an early Euro-American landowner in the region.

Ancient seas that once covered the area are the source of the salt. As the water evaporated, large deposits of salt remained in geologic basins that were later buried under thousands of feet of sediments. Since the density of salt is less than the surrounding sediments, it often moves upward toward the surface, forming underground domes of pure salt. Although not as well-known as the prominent coastal domes such as Avery Island and Weeks Island, the basin underlying North Louisiana contains nineteen salt domes. The tops of the nine domes in Winn Parish, including the one that created the environment for Drake’s Salt Works, are about a thousand feet below the surface. When ground water exposed to the domes nears the surface saturates the soil, barren salt flats (salines) often form where plants can’t survive. The Drake’s Salt Dome created several salines composed of salt-impregnated clay that varied in size up to four acres.

Archaeological research indicates the salines at the Drake’s Salt Works site were among the most heavily utilized in the south-central United States between 1650 and 1850. Well-documented accounts reveal that the Caddo peoples actively participated in the production and trade of salt there beginning around 1600. Two Caddo bands living nearby, the Natchitoches and the Doustioni (translated as “Salt People”), were involved.

The salt-making process consisted of pouring water over baskets of salt-laden soil and catching the resulting brine in clay bowls that were made on site. The bowls were then placed in a fire to boil off the water, leaving cakes of high-quality salt. A member of Hernando de Soto’s expedition (1539–1543) described the procedure from his observations at another saline in present-day Arkansas:

The salt is made along by a river. . . As they cannot gather the salt without a large mixture of sand, it is thrown together into certain baskets they have for the purpose, made large at the mouth and small at the bottom. These are set in the air on a ridge-pole; and the water being thrown, vessels are placed under them wherein it may fall; then, being strained and placed on the fire, it is boiled away, leaving salt at the bottom.

Other early historical accounts support the idea that salt-making at Drake’s Salt Works was conducted mostly by Caddo women.

After the salt cakes were produced, they were dried for storage and made ready for transportation. Early trading partners were Native American groups in their vast web of trade networks and, besides other Caddo bands, included Koroa, Natchez, Ouachita, Taensa, Tunica, Quapaw, and Wichita. Beginning in the late seventeenth century, a major economic shift expanded the salt trade as sustained contact with the French and Spanish developed throughout the region. French-Canadian explorer Louis Juchereau de St. Denis recorded that trade between the Natchitoches and French began in 1701, and salt was the main article of commerce. In reference to the quality of the salt, St. Denis stated that “the salt secured from these Indians is whiter and purer than the salt that came from France.” The colonial settlers required salt to preserve meat (an uncommon practice among Native Americans), and for tanning as the trade in animal hides surged. Additionally, the founding of the French village of Natchitoches in 1714 provided a nearby trading post for the salt works. Salt making persisted at Drake’s Salt Works by the Caddo until soon after 1800, when in 1805 the American “Indian Agent” John Sibley wrote that only two old Indian men continued to produce salt there.

American settlers moving into the region after the Louisiana Purchase soon tapped the commercial potential of the old salt works. Of the several salines at Drake’s Salt Works, settlers concentrated their efforts on the east side of Saline Bayou, opposite the side where Native Americans worked. In 1812 Major Amos Stoddard stated in reference to the entrepreneurs that “seven laborers produced 240 bushels of salt per month, at an expense of $40.” It was sold locally for one to two dollars per bushel, and by 1816 salt from Drake’s was being regularly transported as far as Natchez and New Orleans.

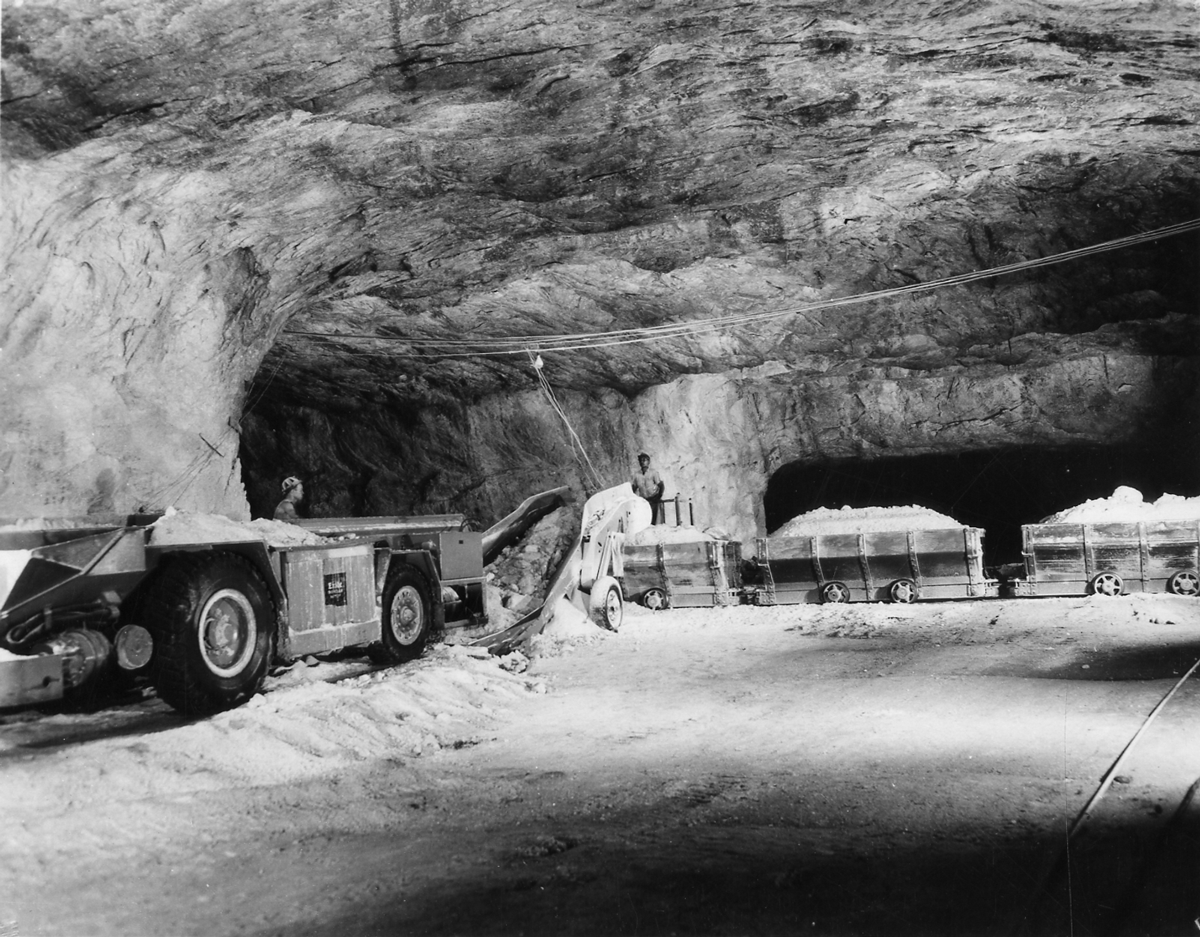

The interior of nearby Carey Salt Co. in the 1940s. State Library of Louisiana.

Production at the works increased greatly with the introduction of modern technology—iron and copper equipment, including furnaces, and wells that were dug and bored to obtain large quantities of brine. One such well bored by Reuben Drake was more than a thousand feet deep and encased with hollowed pine logs. A reservoir was constructed to contain the brine until it was processed. The heyday was short-lived, though, as competition from elsewhere encroached. In the May 23, 1879 edition of the Ouachita Telegraph, a reporter recorded his observations of the site in 1859:

Here in a wilderness country are to be seen the ruins of an enterprise the extend [sic] and cost, of which everything considered, are truly astonishing. The levee itself is a magnificent work and confined at one time a body of water which would now appear to have been inexhaustible . . . the mills are idle and will remain worthless until some shrewd capitalist comes along and secures the fortune they will undoubtedly yield with prudent management. But that which most surprised and interested us was the exploded Salt Works. . . Here were aqueducts of near a mile in length conveying the Saline water to the main reservoir and from thence to the place of final preparation. Here were huge kettles, several furnaces, a steam boiler, a copper tube about 500 feet in length and more than a foot in diameter, a continuous row of large salt water vats or receptacles capable of holding many thousand cubic feet of water. . . Here, too, is perhaps the only genuine Artesian well in the State, at least in this portion of it. From a depth of over 700 feet the water comes boiling up covered with a foam as white as the driven snow and as clear as the blue waters of the sea.

The “shrewd capitalist” mentioned above never appeared. Instead, the Civil War arrived. When the Union blockade eliminated the South’s importation of European salt, the North Louisiana salines were temporarily revitalized by the Confederacy desperate for salt to cure meat for their armies. More than a thousand enslaved people were forced to work the region’s salt works including Drake’s. The Confederate government paid producers ten to fifteen dollars per bushel, and salt, which initially sold domestically for twenty cents per pound in 1863, went for two dollars in 1865. After the war, the salt works were shuttered for good when cheap salt from other areas, including new rock salt mines, became available. In 1879 the same reporter concluded, “The works are nothing but ruins now, but the place is noted for its fine fishing, mineral waters, and salt-water bathing. Pleasure-seekers and invalids visit it annually, and some remarkable cures are reported as having been made there. . .”

Today, wild animals are once again common visitors to Drake’s Salt Works.

Kelby Ouchley is a biologist and writer who managed National Wildlife Refuges for the US Fish and Wildlife Service for thirty years. Since 1995 he has written and narrated Bayou-Diversity, an award-winning weekly conservation program for public radio. His seven published books include a historical novel, natural histories of Louisiana, a comprehensive book on alligators, and a dictionary for naturalists. His latest book, Bayou D’Arbonne Swamp: A Naturalist’s Memoir of Place, won the 2023 John Burroughs Medal for excellence in natural history writing.