Winter 2016

Shopping Crossroads

As a major metropolis from the late 18th century to today, New Orleans has always had a strong tradition of retail activity

Published: December 8, 2016

Last Updated: October 26, 2018

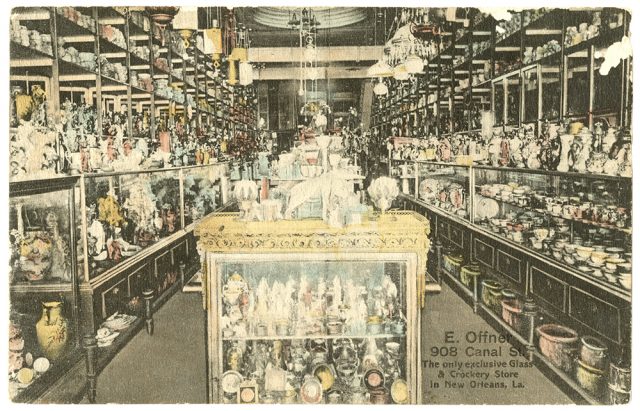

New Orleans’s retail activity was complemented by related industries. In the early 19th century, several silversmiths and goldsmiths, or orfèvres, practiced in the French Quarter. Some of these craftsmen made regular trips across the Atlantic to acquire merchandise and study the latest trends to reproduce for their local customers. European styles and wares also came to the city through china importers on Chartres and Canal streets, who filled their windows with colorful transfer-printed earthenware and sleek porcelain dishes that had just arrived on ships from New York; Staffordshire, England; and Le Havre, France.

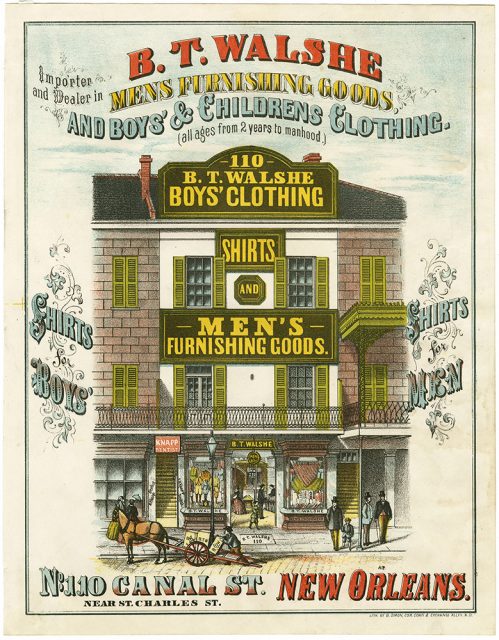

B.T. Walshe advertisement, 1870, by Marie Adrien Persac (draftsman); Benedict Simon (lithographer).

By the mid-19th century, the first blocks of Royal Street were designated “Furniture Row.” Store after store offered parlor suites, beds, dining sets, carpets, curtains, mirrors and miscellaneous “fancy goods” in the latest Victorian styles, which were largely revivals of earlier rococo, Gothic and Elizabethan styles. Retailers such as Prudent Mallard, William McCracken and Henry Siebrecht received constant shipments of furniture from manufacturers in New York, Boston, Cincinnati and France to fill their warehouses. They employed craftsmen to assemble, upholster and install new furniture, curtains and wallpaper for their customers in the city and up the river, but very few of their goods were actually made in New Orleans.

After the Civil War, large plate-glass shop windows along Canal Street were dedicated to glittering luxuries. Local newspapers reported on the diamond jewelry, marble statues, regulated clocks, patented pistols and specialty china and silver services that filled the best windows. Retailers competed with each other to have the most impressive objects on view: when one jeweler displayed a miniature fire engine as a prize for a local fair, another made a true-to-life silver and gold model of the mule-drawn streetcars that traveled up and down Canal Street. Silver retailers, including Hyde & Goodrich and their successors A.B. Griswold & Co., E.A. Tyler and M. Schooler, employed craftsmen to handle custom orders, which they sold alongside the popular silver patterns produced by northern manufacturers. China emporiums up the street were filled with all types of fancy and plain ceramics, available to shoppers at any price point.

At the turn of the 20th century, department stores became the anchors of the shopping district on Canal Street. Many of these large stores—with departments dedicated to women’s clothing, men’s furnishings, toys, stationery and “bric-a-brac”—got their start as dry goods stores. Daniel Henry Holmes started his dry goods business on Chartres Street before moving to Canal Street in 1849, and D. H. Holmes became one of the most popular department stores in the city. Leon Godchaux began selling dry goods from a peddler’s cart in the 1840s, and within two decades he had a thriving furnishings store, Godchaux’s, selling ready-made clothing for men and children. In 1892 Godchaux’s moved into a new “skyscraper-style” store near the corner of Canal and Chartres streets and began expanding its merchandise to include women’s clothing and household items. A few years later, S. J. Shwartz, with help from his father-in-law, Isidore Newman, expanded his dry goods business into a grand, white building—the Maison Blanche, which was purpose-built to house an extensive assortment of new goods, laid out in separate departments throughout the store.

Postcard depicting interior of E. Offner’s ca. 1910. Courtesy of THNOC, gift of Charles L. Mackie.

At the same time, old furnishings gained value in the antiques stores that were established on Royal Street beginning in 1881. These stores, such as Waldhorn’s, Keil’s and Manheim’s, carried on the legacy of shopping established by earlier purveyors. To meet local demands, they imported antiques from France and the northeast, selling them alongside heirloom pieces that had originally been purchased on the shopping thoroughfares of old New Orleans.

Lydia Blackmore is curator of Decorative Arts for The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Editor’s Note: This article references an exhibit that is no longer on view. For current exhibits at the Historic New Orleans Collection, please visit www.hnoc.org.