Summer 2017

Sights and Sounds of Storyville

The Historic New Orleans Collection has an exhibition complementing the recently published book, "Guidebooks to Sin"

Published: June 8, 2017

Last Updated: July 8, 2019

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, Gift of Albert Louis Lieutaud, 1957.101

View of Basin Street; ca. 1908.

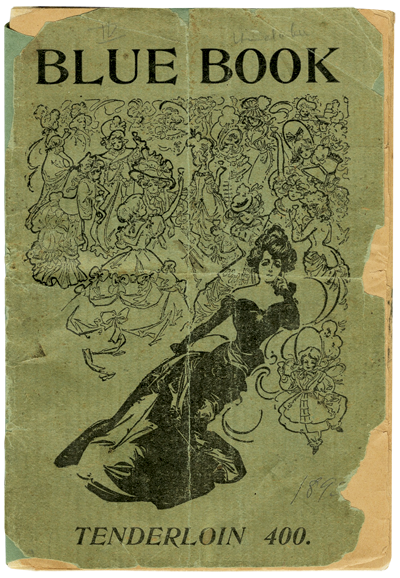

Blue Book, Tenderloin 400; New Orleans, 1901. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection, 1969.19.4

For most of Storyville’s brief existence, visitors to the District might navigate the neighborhood and its services with the help of special guidebooks that contained directories of prostitutes listed by name, address, and race, as well as advertisements for individual establishments and luxury products. Though these publications became known collectively as blue books, not all of them were published under that name. The most famous of these guides are editions of a publication titled Blue Book, which was issued annually in expectation of increased visitors to the city during Carnival. Blue Book was compiled by William Struve (ca. 1872–1937) under the pseudonym “Billy News.” A former police reporter for the New Orleans Item, Struve was a close friend and associate of Thomas C. “Tom” Anderson (1858–1931), an entrepreneur, state legislator, and the so-called Mayor of Storyville. The term blue book is also used to refer to other New Orleans prostitution guides such as Hell-O, New Mahogany Hall, and even, ironically, The Red Book. New Orleans was not the first, nor the only, city whose vice district had its own guides, but blue books were probably produced more regularly than other cities’ prostitution guides. The earliest extant blue book appeared around 1898 and the last between 1913 and 1915.

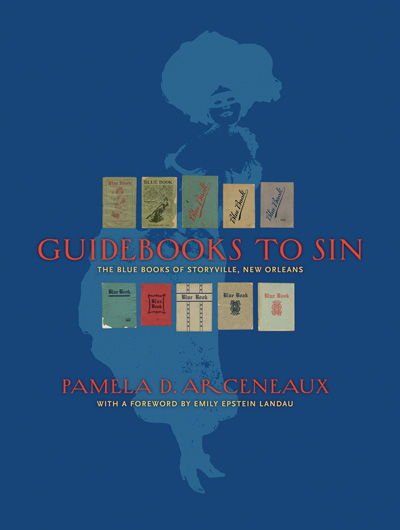

Guidebooks to Sin:

The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans

by Pamela D. Arceneaux

with a foreword by Emily Epstein Landau

The Historic New Orleans Collection

2017 • hardcover • 9″ × 12″

160 pp. • 320 color images

Targeting a white male audience, the Storyville-era guides featured advertisements for liquor, beer, cigars, restaurants, and venereal disease cures. By modern standards, the tone of these guides is demure. None of the blue books specifically describe the women, sexual services offered, or the fees for such services. Some contain photographs of brothel interiors and images of people and venues. Years after Storyville closed, several fakes and facsimiles were published, trading on the District’s bawdy legacy. A selection of blue books from THNOC’s holdings will be on view upstairs at 410 Chartres Street—a complement to THNOC’s recently published volume Guidebooks to Sin: The Blue Books of Storyville, New Orleans.

Twenty years into the experiment, the District was in a state of decline, facing pressures from social and political changes sweeping the nation, including the country’s entry into World War I. In 1917 the federal government prohibited open prostitution within five miles of any military installation, forcing the closure of red-light districts across the nation. The curtain fell on Storyville on November 12, 1917.

Following the official closure of Storyville, the District slowly began to wither away. Many women and madams, such as Lulu White, attempted to continue practicing their trade in spite of growing legal troubles. The music clubs, once bustling, became less popular without the nearby allure of the sex trade. A number of the once grand buildings were demolished in the 1930s to make way for the public-housing development called the Iberville Housing Project that was constructed over much of the site in the 1940s. Despite its demolition, Storyville remains a part of New Orleans’s complex identity.

Editor’s Note: This article references an exhibit that is no longer on view. For current exhibits at the Historic New Orleans Collection, please visit www.hnoc.org.