Winter 2015

Soul of the South

An exhibition at the Louisiana State Museum reveals the boundless creativity and eccentricity of Southern artists.

Published: December 16, 2015

Last Updated: June 28, 2023

Courtesy of the Louisiana State Museum, gift of the Gitter-Yelen Foundation, 1998.025.044

James “J.P.” Scott, New Orleans Ferry, circa 1990, wood, metal rubber, paint and mixed media.

Much of the collection was on display in Madame John’s Legacy, part of LSM, from 1999 to 2005, when the effects of Hurricane Katrina necessitated its removal. The long process of renovation and repair to LSM properties because of storm damage, together with other LSM commitments of space and time, all conspired against reinstallation. Now, after a hiatus of 10 years, LSM is fortunate to be able to present Soul of the South: Selections from the Gitter-Yelen Collection, an exhibition at the Old U.S. Mint of more than 60 two- and three-dimensional works of art from the Collection. The exhibition demonstrates the salience of contemporary Southern self-taught art in Louisiana’s history, which nicely dovetails with the LSM mission of addressing Louisiana history and culture. Like the exhibition at the New Orleans Museum of Art, Pierre Joseph Landry: Patriot, Planter, Sculptor, which NOMA developed in partnership with LSM (on view through March 20, 2016), Soul of the South reveals the enduring appeal of art created outside of the traditional academic or professional framework.

Terms such as outsider, visionary and nontraditional capture particular stylistic and historical affinities, but none of these terms adequately describes the range or character of the art …

Throughout the years, collectors, scholars and admirers have struggled to define this art. Terms such as outsider, folk, naive, visionary and nontraditional capture particular stylistic and historical affinities, but none of these terms adequately describes the range or character of the art in Soul of the South. Yelen prefers the term self-taught, which, as she wrote in the 1993 catalogue Passionate Visions of the American South: Self-Taught Artists from 1940 to the Present, aptly suggests the common impetus to paint, sculpt or draw “without knowledge of the artistic mainstream” and a shared “unbidden inner drive” that compels creativity.

Most of the artists in Soul of the South embarked on a career with little expectation of remuneration, and many such as Sister Gertrude Morgan and Howard Finster, believed that their art served a higher purpose. For example, Morgan’s Do You Know Him?, 1970, and Finster’s Life and Death, 1986, may be seen as extensions of the artists’ religious convictions. Morgan believed that she was the literal bride of Christ and that her paintings could inspire revival, and Finster claimed to have received divine inspiration to devote his life to painting sacred art. Both artists were enormously productive; Finster is estimated to have created more than 10,000 works of art. After an accident in 1960 left him unable to work, David Butler began making metal cutouts such as Creature, 1975, to decorate his house and adorning his yard with whirligigs in an effort to ward off evil spirits. Butler envisioned a totemic function for his art far removed from the aesthetic value that is evident when his art is placed in a museum context.

- James “J.P.” Scott, New Orleans Ferry, circa 1990, wood, metal rubber, paint and mixed media, Louisiana State Museum, Gift of the Gitter-Yelen Foundation, 1998.025.044

- Sister Gertrude Morgan, Do You Know Him?, circa 1970, oil on paper. Louisiana State Museum, Gift of the Gitter-Yelen Foundation, 1998.025.029

- : Bill Traylor, Man with One Leg, circa 1945, crayon on paper, Louisiana State Museum, Gift of the Gitter-Yelen Foundation, 1998.025.106

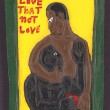

- Herbert Singleton, Love that Not Love, circa 1990, acrylic on wood, Louisiana State Museum, Gift of the Gitter-Yelen Foundation, 1998.025.049

- Mose Tolliver, Man and Birds, circa 1985, enamel on plywood, Louisiana State Museum, Gift of the Gitter-Yelen Foundation, 1990.025.105

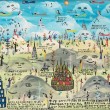

- Howard Finster, Life and Death, oil on canvas. Louisiana State Museum, Gift of the Gitter-Yelen Foundation, 1998.025.074

The earliest work of art in the exhibition is a drawing created by Bill Traylor. Born a slave in 1854, Traylor began to draw at the age of 84 using colored pencils, crayons and poster paint to create intimate scenes such as Man with One Leg, 1940, on scraps of aged cardboard. Charming ambiguities of space and perspective characterize this work, which also invites associations with autobiography since Traylor lost a leg in the 1940s. Clementine Hunter also painted scenes from her experience in a deceptively simple style. Untutored and introduced to art late in life, she painted from memory, documenting the never-ending flow of domestic and agricultural work, punctuated by a marriage, a funeral, the birth of a child or a card game. African Head, circa 1975, pays homage to her identity and achievement as a woman rising from humble beginnings to become one of the most recognizable self-taught artists in the South.

Despite the challenges many of these artists faced—including poverty, debilitating accidents, mental issues and institutional racism—hope and faith in spiritual matters and the value of hard work remain constant themes.

Not all of the artists in the exhibition are household names, and a major goal of Soul of the South is to reveal the range of expression beyond figures such as Morgan, Finster, Traylor and Hunter. Born in Alabama, Sybil Gibson began her life as an artist in 1963. She was inspired to paint fruit, flowers and themes associated with feminine subjects such as 4 Faces, 1991, on brown paper bags. Insecure about others’ appreciation of her art, she would on occasion abandon her home leaving her paintings strewn about the yard. Although not as well-known as Clementine Hunter, M.C. “Five Cents” Jones mirrored Hunter’s themes and penchant for vibrant colors. Like Hunter’s paintings, Blue House with Donkey (Picking Cotton), circa 1985, suggests a pastoral sense for the bygone days of plantation life. However, Jones often captured the more sinister aspects of rural life in the South, including the menacing presence of the Ku Klux Klan. “Prophet” Royal Robertson, a native of Baldwin, Louisiana, is another less familiar self-taught artist from the South whose subjects are not always optimistic. Drawings such as Dream Findly I Died/The Prophecy, circa 1985, focus on his challenged relationship with women after his wife Adell left him. Through image and text, Robertson denounces women in general as “whores” and “vipers” and with other misogynistic epithets tempered, so to speak, with biblical quotation.

Despite the challenges many of these artists faced—including poverty, debilitating accidents, mental issues and institutional racism—hope and faith in spiritual matters and the value of hard work remain a consistent theme. James “J.P.” Scott is an example of this tendency. The son of a fisherman, he began building model boats that were surprisingly accurate, if idiosyncratic, replicas of working vessels such as New Orleans Ferry, circa 1990. Scott sold his works, but not until he had displayed them long enough for him to judge their faithfulness both as replicas and as artistic statements. He adorned them with salvaged pieces of net, seashells and handmade flags and signed each with bold bas-relief carved letters. However, there are limits to the search for consistency among the artists in Soul of the South. As Yelen wrote in Passionate Visions, “the commonality among self-taught artists springs from their untutored creativity and personal vision, not from a shared technique, style or ideology.”

The authenticity of vision and passion underlying the expression inspired Gitter and Yelen to embark on a journey to collect contemporary American self-taught art. As Yelen recalled, seeing a New Orleans Museum of Art exhibition of Sister Gertrude Morgan’s paintings and drawings, organized by William Fagaly, propelled them on this trek. Gitter and Yelen were not merely passive collectors. They met and, in many cases, befriended a number of the artists featured in Soul of the South. Through multiple purchases and personal relationships, they provided enduring support for the artists and their work. Gitter described the couple’s engagement with contemporary self-taught American art as “one of the most memorable and engaging of all our experiences as collectors.”

Soul of the South will be on display through May 28, 2017, at the Old U.S. Mint, 400 Esplanade Ave., in New Orleans. For more information, visit louisianastatemuseum.org.

________________

Richard Anthony Lewis, Ph.D., is the curator of visual art at the Louisiana State Museum.