Sound Advice

Commodifying Traditional Music

The prolific, controversial career of Ralph S. Peer

Published: November 28, 2017

Last Updated: December 19, 2018

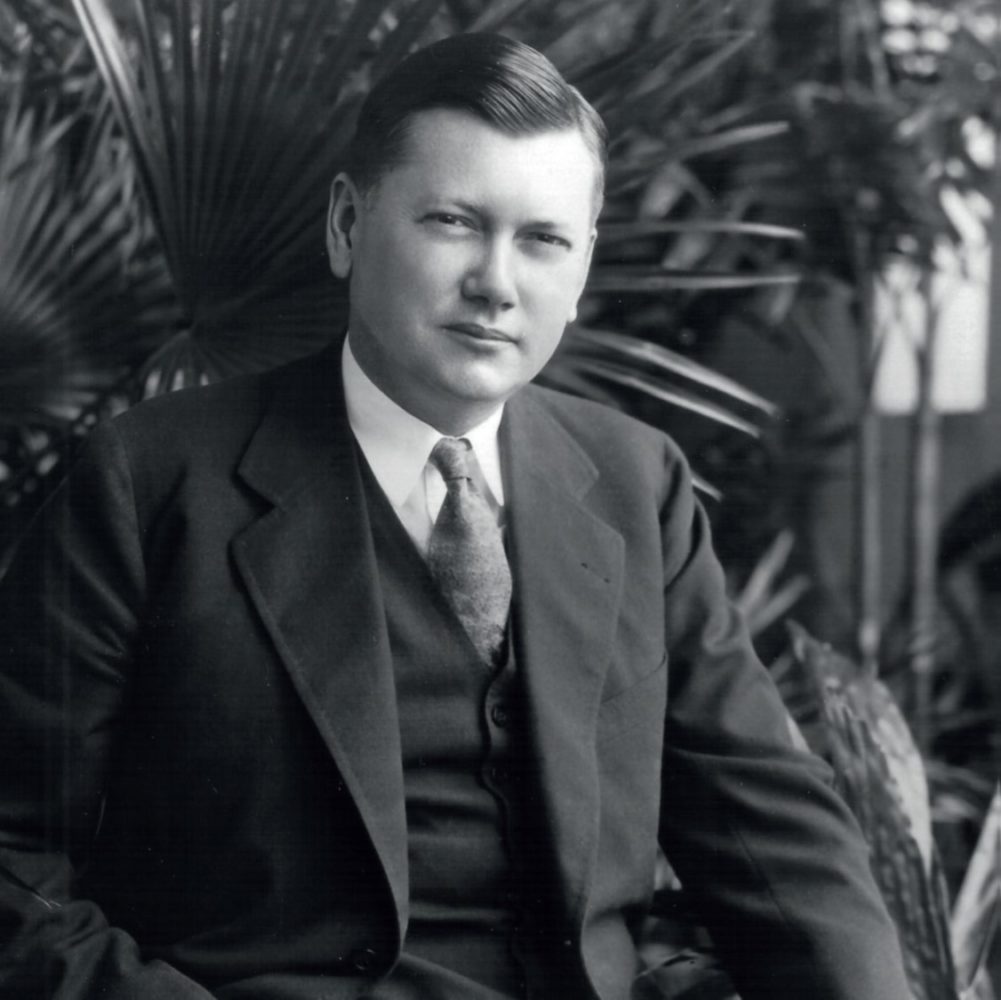

Courtesy of Birth Place of Country Music Museum.

Ralph Peer is the subject of a new three-disc anthology.

These comparatively remote regions were home to a wealth of traditional songs, many of which could not be definitively linked to any specific songwriter. As a result, a vast field of great music lay fallow in terms of monetization. This absence of attribution allowed the record companies to make slight changes to traditional songs and then present them as original new compositions, to which they owned all the rights. This practice quickly became the norm in the record business, especially in the fields of blues and country—and particularly due to the energetic efforts of the music mogul Ralph S. Peer (1892–1960.) The improbable breadth, depth, and lasting influence of Peer’s career is explored on the recently released three-CD, fifty-song compilation The Roots of Popular Music: The Ralph S. Peer Story (Sony Latin). Without Peer’s peripatetic and productive presence on the ’20s and ’30s recording scene, many of the great songs heard on American Epic’s anthology would likely not have been captured for posterity. Unlike American Epic, however, the Peer anthology includes recordings made from the 1920s through the ’50s, when Peer was still active, and on up to the present day. At this writing, the Peer publishing empire, currently controlled by his son, has thirty-two offices in twenty-eight countries and owns the rights to more than a quarter of a million songs. Accordingly Peer’s legacy still looms large in music-industry circles.

These statistics mean nothing to the general public, to whom Peer is all but unknown. Nevertheless, the public has long adored Peer’s work as a record producer. (In Peer’s era, the term “producer” had yet to emerge; people who crafted recordings and decided which ones to release, among a wide array of other duties, were referred to by the gender-specific descriptor of “A&R men.” The abbreviation stood for “Artists and Repertoire.”) From 1920 to 1932—working successively for the Okeh, Columbia, and Victor labels—Peer personally supervised and produced or commissioned the recording of a voluminous body of songs that are now revered as beloved, seminal classics of country, blues, popular song, and jazz.

A cursory list of the artists he recorded includes Jimmie Rodgers, The Carter Family, Blind Willie McTell, Fats Waller, and many more. He traveled tirelessly, setting up temporary studios in various Southern cities and holding auditions that drew hopeful musicians from miles around. Peer summarily rejected the vast majority of those who tried out. He had an uncanny knack for gauging who had the intangible quality to make hit records, and which of their songs had the best potential.

This high rate of success is quite curious, given that Peer did not come from a musical background. His father was a storekeeper whose wares included record players, and Peer entered the industry by working for a company that manufactured such devices in his hometown of Kansas City. As a son of the Midwest, Peer had no Southern roots, and no evident affinity for Southern music. He felt no calling to be a folkloric preservationist à la John and Alan Lomax, whose non-commercial work for the Library of Congress overlapped somewhat with his for-profit operation. Nevertheless, Peer’s prolific recording of traditionally rooted music inspired the noted folklorist Archie Green to call him “a cultural documentarian of the first rank.”

What appeared to drive Peer, more than any passion for music, was a keen, innate, and inventive aptitude for business.

What appeared to drive Peer, more than any passion for music, was a keen, innate, and inventive aptitude for business. He might well have prospered by marketing any number of non-musical products. At one point, in fact, between working for Columbia and Victor, Peer seriously considered a career in the national sale and distribution of apple pies. For those who love American vernacular music, it is fortunate indeed that Peer deserted desserts and returned to the record business.

A cross-section of hits from Peer’s early field trips appears on the Sony compilation. They include such country favorites as The Carter Family’s“Keep On The Sunny Side” and Jimmie Davis’ “You Are My Sunshine” (Davis went to become Louisiana’s governor in 1944); Tommy Johnson’s haunting “Cool Drink of Water Blues”; and the raucous “Stealin’, Stealin’” by The Memphis Jug Band. Equally important in Peer’s legacy is Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues,” recorded in an established New York studio, which sold more than eight hundred thousand copies and is regarded, in some circles, as the very first blues record. Peer also signed the great popular songwriter Hoagy Carmichael, whose poignant “Georgia On My Mind” appears on the anthology in a soulful interpretation by Ray Charles, recorded in 1960.

Always seeking new angles, Peer arranged innovative pairings of established artists from different genres—albeit uncredited—as heard here in Louis Armstrong’s instrumental accompaniment of Jimmie Rodgers on “Blue Yodel Number 9.” Rodgers was country music’s first major star, and his collaboration with Armstrong was less of a stylistic leap than might be assumed. Rodger’s vocal style was steeped in African-American blues, and Armstrong was a versatile professional who explored many different genres with great confidence and verve. Peer’s bold vision also included recording such important figures, not included on this anthology, as King Oliver’s band, with Louis Armstrong as a sideman, in 1923. In 1925 and ’28, Armstrong stepped out as a bandleader, on his historic Hot Five and Sessions (also not included here), as exquisitely exemplified by “West End Blues.” For these astute artistic choices Ralph Peer is rightly regarded as an important contributor to Louisiana music.

Cover for the sheet music to Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues,” (written by Perry Bradford); Smith’s recording of it sold more than 800,000 copies.

In 1932 Peer left the record business per se to focus on expanding his music-publishing empire. Having already amassed a vast catalog of Southern American songs, sung in English, Peer turned his attention to the music of Latin America, sung in Spanish. With his powerful connections, Peer could easily arrange record deals for the artists who performed the songs he owned. For example, Desi Arnaz—a Cuban émigré who became an American television star on I Love Lucy—climbed the Billboard pop charts in 1947 with the fiery “El Cumbanchero.” A riveting orchestral/big-band arrangement by the Puerto Rican émigré Rafael Hernández showcased Arnaz’s impassioned singing. Peer similarly assisted the percussionist and live-wire “Nuyorican” performer Tito Puente, heard here on “Ran Kan Kan.”

In a broader sense, Peer is credited in the music industry with creating a rumba/mambo fad and a broader general craze for Latin music that lasted roughly from the ’40s into the ’60s. And, in his later years, songs that Peer owned would suddenly reappear in unexpected new interpretations, such as Elvis Presley’s romping rockabilly version of “Blue Moon of Kentucky” from 1959. In its original form, “Blue Moon of Kentucky” was a delicate, lovelorn lament by the mandolinist and singer Bill Monroe, a pioneer in the evolution of the bluegrass genre.

Ralph Peer amassed great wealth as a music publisher. Unlike many of his acquisitive contemporaries, however, he did so ethically. Most record-company executives went beyond garnering the copyrights to a song by also crediting themselves as the song’s writers. This sleazy and disingenuous, but quite common, practice cheated the actual songwriters out of income from recurring royalties. Substantial money could be involved if a song became a hit. (When a record is sold, there are three streams of income: for the recording artist, the song’s writer, and the song’s publisher, besides what goes to the record company.) Peer, to his great credit, never claimed to be a songwriter. He allowed the musicians whom he recorded to retain their writer’s shares. In return they agreed to grant Peer ownership of the music publishing and copyrights, and to only write future songs for him. Songwriting credits from the 1920s and ‘30s can still generate significant income for the writer’s heirs.

While Peer was primarily known as a private man who worked behind the scenes, he occasionally made such absurd and insulting public statements as “I invented Louis Armstrong!” As was true of many white people of his generation, the “n-word” was part of Peer’s everyday lexicon. Beyond exhibiting such racism, Peer could also be quite condescending and elitist towards the rural white Southern musicians who had helped make him rich. These biases prompt the puzzling question of why Peer chose to work among people whom he seemingly didn’t admire, while also demonstrating a rare simpatico ability to choose their best songs and elicit their best performances. Peer has also been sharply criticized for his marketing decisions to designate music by African-American artists as “race records,” and to classify the work of rural white artists as “hillbilly music.” (“Race” was then used as a term of pride among some African-Americans, but “hillbilly” was often considered derogatory, as it is, even more so, today.) By the mid-1930s both categories stood as standard demarcations in the record business, and this division would prevail for another fifteen years.

Depending on one’s perspective, then, Ralph Peer can be viewed as a visionary who shared the wealth, a calculating and bigoted mercenary, a man who loved music far more than he let on—or a contradictory combination of all these traits. For those who wish to delve into Peer’s complex persona, the wealth of music that he recorded, and the socio-cultural context in which his career unfolded, two books are highly recommended: Ralph Peer and the Making of Popular Roots Music, by Barry Mazor (Chicago Review Press, 2015), and Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music In The Age of Jim Crow, by Karl Hagstrom Miller (Duke University Press, 2010.) As the titles indicate, these books’ viewpoints differ significantly. Reading such erudite tomes will be far more illuminating for those who have first invested some time absorbing the music on The Ralph S. Peer Story and American Epic.

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans-based freelance writer, folklorist, and producer and is the former drummer for the Hackberry Ramblers. Learn more about his latest book, Ernie K-Doe: The R&B Emperor of New Orleans, by visiting erniekdoebook.com. The K-Doe biography was selected for the Kirkus Reviews list of best nonfiction books for 2012.