Sparkling Orangine

The Creole creation behind Barq’s

Published: December 1, 2024

Last Updated: February 28, 2025

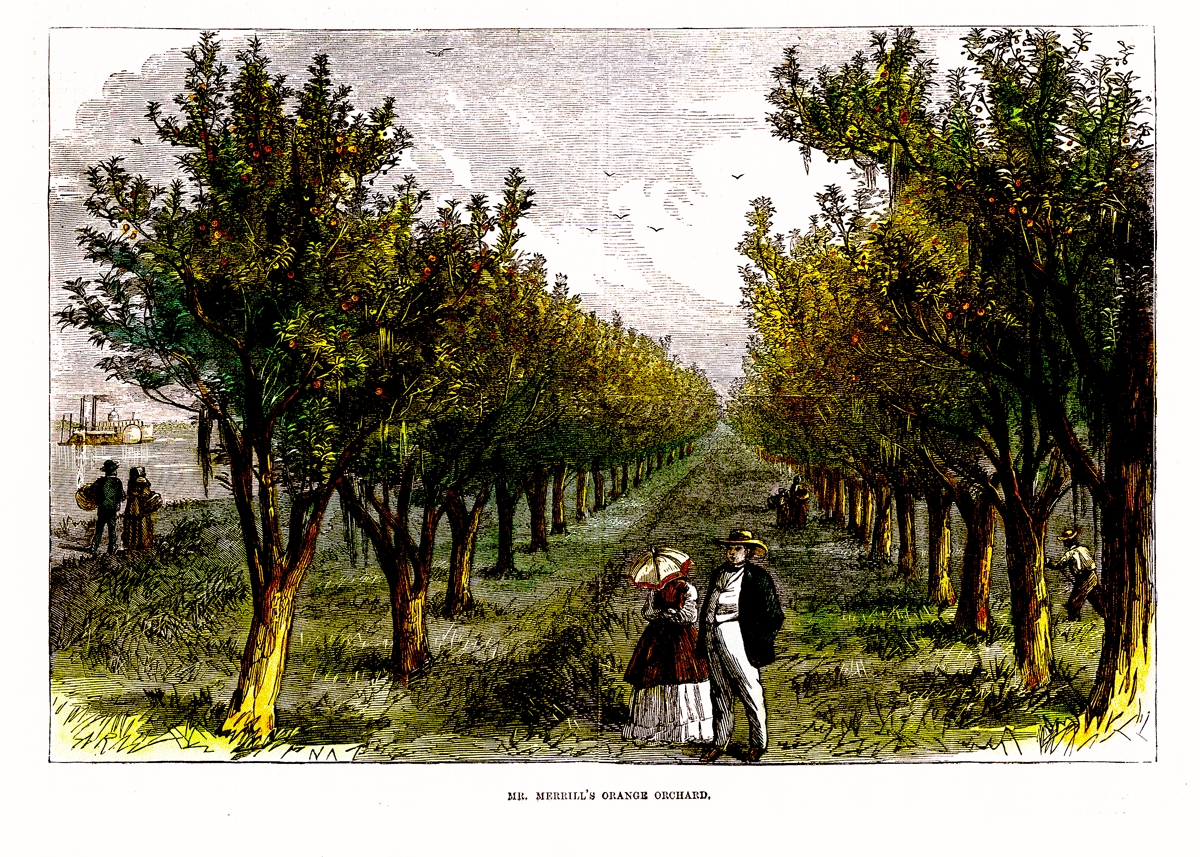

“Mr. Merrill’s orange orchard” from Sketches in Louisiana, 1871

The untimely death of Jules Auguste Barq in the late 1800s left his widow, Marie, with four children under the age of eleven and little support in a federally occupied New Orleans.

Distraught but determined, Marie Barq decided to return with the children to Paris, her birthplace. Marie’s parents had at one time worked as limonadiers, vendors who sold citrus drinks over shaved ice in cafes along the avenues. Her mother had relocated to Couthures-sur-Garonne, a bike ride from Bordeaux vineyards. So begins the story of Barq’s, one of the most iconic soft drink brands in history of America.

Marie’s children—Gaston, Delphine, Jules, and Edouard—all had the opportunity to get formidable French educations. From age 14 to 21, Edouard studied sugar chemistry at the Sorbonne and apprenticed in Bordeaux, where he learned the art of flavorings. These studies would play a large role in what was to become the Barq’s soft drink empire. By 1892 the family had moved back to New Orleans and began selling cordials, mineral waters, and flavored drinks on Royal Street under the name Barq’s Bros.

For one of its flavorful creations, the family sourced citrus grown in the unique ecosystem of Plaquemines Parish. Louisiana’s “Orange Belt” produce was shipped upriver to the French Quarter market. The brothers processed and juiced the citrus through cheesecloth and combined carbonated water with other flavorings. The unique blend went into generic Hutchinson bottles and were sealed with spring-loaded bottle stoppers that created a “pop” when opened. (Hutchinson bottles greatly helped popularize the slang term “soda pop,” though the term predates this era.) The Barq’s brothers named their citrus product “Sparkling Orangine.”

In the sultry days people go a long way out of their course to reach the cool veranda of the Louisiana State Building and drink a glass of orangine, cool and sparkling.

When it was introduced, Sparkling Orangine found immediate popularity in New Orleans, so much so that the family was compelled to run advertisements in daily newspapers to ward off imitators and protect their copyright. The popularity of the drink expanded quickly up and down river transport routes. In 1893 Marie Barq took the Illinois Central train to the Columbian Exposition, informally known as the Chicago World’s Fair. She carried cases of Sparkling Orangine as a participant in the Woman’s Auxiliary World’s Fair Convention.

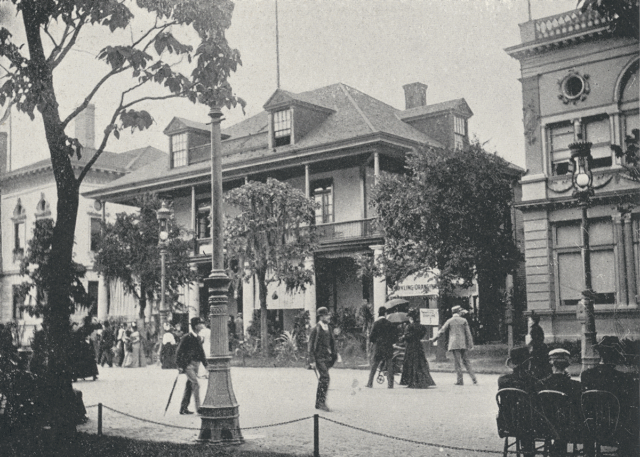

Marie’s efforts to promote Sparkling Orangine in this era of male-dominated industry were significant. The women’s pavilion was unprecedented at a world’s fair; one newspaper covering the expo referred to the nineteenth century as “woman’s century,” with praise for the Exposition’s Board of Lady Managers, Mrs. Bertha Palmer, a prominent socialite, wife of the Chicago mayor, and advocate for the rights of women and children. Stationed next to the Louisiana State Building under an umbrella branded with “Sparkling Orangine,” Marie sold her product over shaved ice.

A correspondent writing from the Fair for the Meridonial in Abbeville, Louisiana, describes Marie as “a little old Creole lady, pleasant faced, voluble and looking as though she might have stepped out of the pages of one of George Cable’s romances.” As for her “orange potation”:

Every bottle bears a certificate of purity of contents from the Health Officer of Louisiana. . . . In the fact that her drink is carbonated, a not over dry champagne in taste, is cold, clean and refreshing, and served in an attractive combination of surrounding, and with her pleasant and odd chatter in a patois, lay a success that left her without a drop of orangine in two hours and a goodly store of dimes and nickels. She has been obliged to order enough orangine to “drown all the good people, don’t you see,” she says as she laughs merrily and engages additional help. In the sultry days people go a long way out of their course to reach the cool veranda of the Louisiana State Building and drink a glass of orangine, cool and sparkling.

A detailed account by the Woman’s Auxiliary World’s Fair Convention ran in the Times-Picayune and included a list of eight Auxiliary awards given to participating Louisiana women. One went to Marie Barq for Sparkling Orangine, the best beverage on the grounds. An enthusiastic visitor to New Orleans wrote the Times-Picayune editor bemoaning an inability to locate “some of the delicious Orangine” that had been on sale at the Fair: “Why at this time of the year you ought to fairly poke at us strangers with such local concoctions as Orangine!” While Sparkling Orangine did not win a gold medal at the fair—it seems “gold medals” were not in fact among the awards granted that year—the claim would be employed in advertising at the turn of the century to shore up Barq’s bona fides along the Gulf Coast.

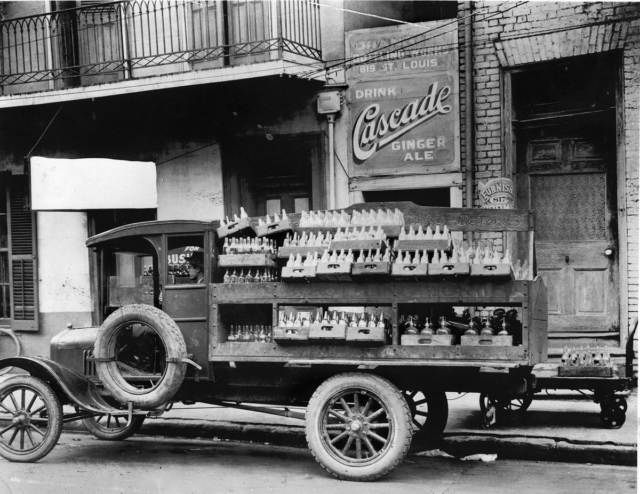

1920s Ford delivery truck. Photo by George François Mugnier

After the untimely deaths of both Edouard’s brothers, the New Orleans company went bankrupt. Edouard married, and, in 1898, started anew on the Mississippi coast. With Elodie, his young wife, Edouard purchased Biloxi Artesian Bottling Works and recommenced the manufacture and sale of mineral water, sodas, and Sparkling Orangine, with expanded offerings and new flavor experiments. Business flourished in the popular resort and seafood processing destination. Marie Barq, who had joined Edouard on the coast, traveled to the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, informally known as the St. Louis World’s Fair, and was awarded a Bronze medal for Sparkling Orangine. Citrus produced in Plaquemines Parish and used in the drink was also on exhibit at the Fair.

Marie ultimately moved on to Washington DC to pursue Civil War claims made by her deceased husband against the government; there she ended up teaching at an all-girls preparatory school. Meanwhile, ten-year-old Jesse Robinson, an impoverished Long Beach native, had begun working for Edouard Barq upon his arrival on the Mississippi Coast. Over the next eleven years, Robinson was an eager apprentice, applying himself in all areas of manufacturing and developing a close bond with Barq. At twenty-one, Robinson set out to New Orleans to fulfill his dream of following in his mentor’s footsteps and build a soft drink business of his own. With Edouard Barq’s blessing and guidance, Jesse started producing Sparkling Orangine.

The Louisiana State Building at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. Note the umbrella stand in the right corner with the words “Sparkling Orangine.” Courtesy of Northern Illinois University Digital Library

By 1909 newlyweds Jesse and Marie began bottling out of a back room at Pete Herman’s Ringside Café at 942 Conti Street. They hung a shingle in the Quarter at 819 St. Louis Street—Orangine Bottling Works—having dropped “sparkling” from the product name. Orangine, seltzer, Cascade Ginger Ale, and other products were distributed in the Quarter via wheelbarrow before the Robinsons acquired a Ford delivery truck. The couple registered a trademark, “Orangine The Gold Medal Drink,” in 1924 and designed a six-ounce Art Deco bottle for the product, hand-sealed with a metal crown. Local newspaper editorials lyrically touted Orangine as “a formula brought from France and one of the business romances of New Orleans.” The Southern Yacht Club’s newsletter Barometer referred to “that delicious, sparkling and refreshing beverage ‘Orangine,’ carried in many of the yachts as part of necessary stores for a cruise.”

In Biloxi Barq replaced Sparkling Orangine with a new orange beverage, trademarked in 1939, called Moon Glo. Robinson’s production of Orangine in New Orleans continued well into the ’50s. But several factors led to both Robinson and Barq tapering off manufacture of these products. The seasonal nature of citrus, its laborious processing, and shelf-life issues proved difficult to navigate. Market share did not justify the continued investment in custom bottles dedicated to a single flavor. Like many other beverages, both Orangine and Moon Glo were eventually replaced with an artificially flavored product—more convenient, consistent, and cost effective—and simply referred to as orange soda. However, the early success of Sparkling Orangine laid the foundation for the development of Barq’s root beer, released in 1934, which came in a unique diamond-shouldered bottle and took the Gulf Coast culinary culture by storm.

Today, Barq’s is one of the oldest and most successful soft drink brands in the world, now owned by the Coca-Cola Company. Barq’s root beer is one of the world’s top-selling root beers and maintains its iconic place in southern history. But it all started with Sparkling Orangine.

Veni Harlan is a multi-disciplinary creative based in Baton Rouge who has worked as a writer, graphic designer, photographer, art director, educator, communications specialist, and environmental advocate.