Magazine

Streetcar Stories

New Orleans is the only city that never entirely lost a fleet of electric streetcars from the early modern era

Published: October 2, 2014

Last Updated: May 13, 2019

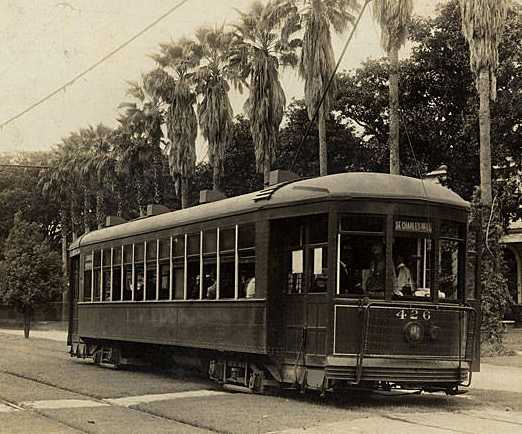

Photo by Sharon Mollerus.

A streetcar on St. Charles Avenue in New Orleans.

San Francisco’s cable cars help to preserve an even older form of urban transit, but most Bay Area passengers have been displaced by tourists; in New Orleans, locals still ride the St. Charles Avenue line to school and to work. Here, nostalgia and utility have managed to co-exist.

Most cities replaced their streetcars with diesel and electric buses during the 1930s and 1940s, and New Orleans generally did the same. By 1954, New Orleans had substituted buses on all of its more than two dozen streetcar lines except the Canal Cemeteries and the St. Charles. The efforts of Streetcars Desired, Inc., and other preservationists failed to save the Canal line, which was replaced by buses in 1964; however, the preservationists did generate enough public support to ensure that the St. Charles line would not be removed.

New Orleans held onto 35 of its vintage streetcars built in 1923 and 1924 by the Perley A. Thomas Car Works of High Point, North Carolina. (The company survives as Thomas Built Buses, one of the largest manufacturers of buses.) Wooden seats, bare light bulbs, and windows that open are a few of the features that set St. Charles Avenue streetcars apart from most transit vehicles. The appeal of this design was noted by renowned New Orleans singer Blue Lu Barker, “The bus – I don’t know – It’s stuffy. But the streetcar, well, you could always look out and wave at your friends – but you can’t do that on a bus.”

The line itself is the world’s oldest continuously operating street railway, dating from the steam railroad service that started in 1835 between New Orleans and the Carrollton resort. In the more than 175 years that streetcars have rumbled through the Crescent City, they have carved out a history both parallel to and distinct from the transportation history of other U.S. cities.

Practical Nostalgia

Vintage streetcars have come to evoke urban nostalgia in one of its most salable forms. The animated feature Who Framed Roger Rabbit? used the lost streetcars of Los Angeles to set the scene in much the same way that the Coen Brothers used New Orleans streetcars in Miller’s Crossing. Filmmakers trust streetcars to project the same nostalgic qualities on screen that civic boosters hope to provide for their cities through antique street railway lines. The most prevalent examples of the trolley’s popularity are the rubber-wheeled parodies of streetcars that hotels and tour bus agencies use to ferry tourists about; somehow, these diesel burning imitations of “turn of the century” streetcars are supposed to improve upon a conventional bus ride.

The general attraction towards streetcars extends beyond amusement. Communities long indifferent to public transit concerns in this era of the automobile typically welcome plans for a street railway through their neighborhoods; similar plans for a new bus line, however, would likely not be so warmly greeted. In their most sophisticated forms, streetcars are returning as light rail vehicles connecting suburban communities with city centers; light rail is often touted as a key step towards rejuvenating cities, cleaning the urban environment and easing automobile congestion. Whether vintage, modern or fake, street railways conjure up positive and unquestioned connotations in the public mind.

Illuminating History

Even in New Orleans, where streetcar icons saturate local culture and the tourist industry, little beyond basic information is commonly known about the vehicles. Despite their popularity and their significant role in the development of cities, streetcars remain largely unexamined.

New Orleans streetcar, 1910s. Public domain.

One aspect of streetcar history that recently has been pursued by academic historians demonstrates how central streetcars were in the lives of city residents. Studies of the numerous streetcar strikes that occurred throughout the United States during the heyday of trolleys reveal the great amount of public sympathy and violence that streetcar strikes generated.

In New Orleans, locals still ride the St. Charles Avenue line to school and to work. Here, nostalgia and utility have managed to co-exist.

Regular passengers—the group most adversely affected by breaks in service—generally supported the streetcar workers when they struck for higher wages, shorter hours, or other goals. This allegiance reflects one of the unique features of streetcar work: theirs was one of the most public of all workplaces. The same riders that might complain about the streetcar company’s monopoly over transit service typically enjoyed jovial relations with its individual employees. “The people were good to us. On the West End line, the people used to give you a gift. For your birthday or Christmas, they’d give you men’s handkerchiefs or men’s black socks or ties,” remembers Marie Finhold, the Regional Transit Authority streetcar historian who served as a motorette and conductorette during World War II.

Veteran motormen and conductors worked in pairs, usually serving the same line for many years. They often became part of the neighborhoods that they traversed several times each day. New Orleans, the nation’s one unbroken link to the era of streetcars, provides wonderful opportunities to recover this “streetcar culture.”

Memories of Riding the Line

Most every New Orleans resident has some streetcar story to tell. Many streetcar employees and passengers remember clearly the mundane pleasures and pains of riding New Orleans streetcars in the early 20th century. Michael Lonergan, a retired cab driver, recalls one especially useful social function of the streetcars. “My mother and father—when we were kids we didn’t realize it—but they used to use the streetcar as a babysitter. Quite often my daddy would give us fifteen cents and say, ‘Look, go get on the streetcar.’ And sometimes he’d say, ‘Make two trips.’ I realized later it was so my mother and father would have a little time together.”

The city’s street life spilled onto its trolleys. Newspaper boys would ride for a couple of blocks to sell papers. Fishermen boarded lines running near the river and sold catfish to the passengers. Transit regulations allowed passengers to carry sacks of shrimp and oysters, but not crawfish, which were deemed too unsanitary. In exchange for a cup of coffee or some other token, small store owners encouraged motormen to serve as delivery men; they would transport groceries, prescriptions, sandwiches and other packages to families living further down the line.

Political rumors were sometimes spread simply by chatting with the motormen and conductors, who could be expected to speak with dozens of passengers before their run ended.

Members of a brass band would occasionally play a song or two to attract larger crowds. Recalled Danny Barker, musician and music historian, “Bass players and drummers … somebody would have to hand you your drums while you put ‘em on the car, on the back platform—to the annoyance of the conductor. The conductor looking at you—you’re a nuisance. Sometimes some conductors say ‘no way.’ ” People who couldn’t afford delivery charges often brought furniture and other large purchases home on the streetcar. One night on an all night or “Owl Car,” a motorman and conductor moved a woman and her belongings into a vacant house after she had been evicted from her apartment.

Many neighbors talked with one another as part of a daily ritual while walking to and from the streetcar. Regular passengers often developed light-hearted friendships with one another as well as the conductors. In at least one instance, a conductor attended the funeral of a longtime rider.

Negotiating the Racial Divide

This 1941 photograph depicts the interior of a New Orleans street car during segregation. A wooden sign reads “For Colored Patrons ONLY.” Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection.

These same conductors were responsible for enforcing segregated compartments on the streetcar. The 1896 “separate but equal” ruling handed down by the U.S. Supreme Court in Plessy v. Ferguson originated from Homer Plessy’s arrest on a steam railroad running between New Orleans and Abita Springs; the federal decision institutionalized racial barriers, and streetcars in New Orleans and throughout the South were re-segregated. Louis Armstrong and many other black children were first made aware of race segregation while riding a streetcar. Originally a permanent wire screen separating “colored” and “white” compartments, the race screen evolved into a small movable sign reading “For Colored Patrons Only.” The conductor would move the sign to accommodate shifting numbers of black and white passengers. During World War II, the influx of soldiers and others from outside the South caused many confrontations, some of them violent. “I happened to speak with this woman who had been a streetcar conductor during the war,” relates Brenda Quant, a New Orleans writer. She said, “ ‘Oh, yeah, the race screens were around for a long time, and they never caused anybody any problem. Nobody ever got hit over the head with one or anything like that. They were never a problem.’ And I was sort of speechless when she said that because that image of being hit over the head was just so appropriate because—yes! Everyday we were hit over the head with this reality—that we had a place that we could not go beyond.” A coalition of black civil rights activists mounted a legal challenge that led to the removal of the screens in 1958.

Cultural Contributions

Streetcars have also made unexpected contributions to New Orleans’ culture. Jazz historians acknowledge that streetcars allowed New Orleans musicians from all areas of the city to hear and play with one another in downtown

clubs and at lakefront amusement parks. West End and Spanish Fort were New Orleans’ versions of the national phenomenon of amusement parks established and operated by street railway companies. Internationally renowned musicians were featured at West End and, for the cost of a ride, musicians and other New Orleanians were exposed to novel musical styles.

The naming of the “po-boy” sandwich stemmed from the generosity of Clovis and Bennie Martin, two former streetcar conductors who operated a restaurant and coffee stand in the French Market in the 1920s. During the 1929 streetcar strike, the Martin Brothers gave free sandwiches to their former union brothers. At about the same time, the Martins worked with their baker, John Gendusa, to develop a longer and narrower loaf of French bread specifically for sandwiches.

John Gendusa, owner of John Gendusa Bakery, tells this story: “There was a newspaper article written that said the Martin Brothers were making sandwiches for the ‘poor boys on strike’, and when the transit workers would go to get a sandwich, they’d say to the Martin Brothers, ‘Give me a poor boy; I’m on strike.’ This stuck, and that’s how the name of the poor boy got to be.” Soon, both the loaves and the sandwiches were termed “poor boys.”

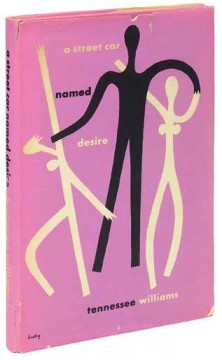

An image of the first edition cover of the 1947 play by Tennessee Williams, “A Street Car Named Desire.” Public domain.

The best known cultural legacy of New Orleans streetcars is Tennessee Williams’ symbolic use of the Desire streetcar line. While living on St. Peter Street in the French Quarter, Williams was completing work on a play that he had variously titled Blanche’s Chair in the Moon and The Poker Night. “He said that from his apartment he could hear that ‘rattletrap streetcar named Desire’ running along Royal Street and the one named Cemeteries running in another direction, and it seemed to be the ideal metaphor for the human condition,” recalls Professor Kenneth Holditch of the University of New Orleans. A Streetcar Named Desire has done more than anything else to establish New Orleans’ reputation as the city of streetcars. Journalists and tourists alike relish the opportunity to make tired references to the play’s title whenever the subject of streetcars arises.

Into the Present Station

More than 90 years old, the St. Charles Avenue streetcars are listed on the National Register of Historic Places and the transit line was recently designated a National Historic Landmarks by the U.S. Department of the Interior. The Regional Transit Authority artisans and maintenance crews are ensuring that they continue to run. Most other cities keep light rail cars and vintage streetcars separate from one another, but these craftsmen allowed the return of the Canal Street streetcar line in 2004 to reflect much of the ambiance of the St. Charles line. Their ability to fashion replicas of the familiar Perley Thomas cars kept modern, boxy-looking light rail vehicles from appearing on Canal Street. Federal regulations such as wheelchair accessibility was satisfied, but the familiar 1920s design complements the utility of a major rail transit line.

Williams’ metaphor of the streetcar as human condition demonstrates that streetcars were never mere transportation. Examining New Orleans streetcar heritage reveals that much of its unique culture was knitted together across time and space by the network of streetcar lines.

––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––

Michael Mizell-Nelson, Ph.D., was an associate professor of history at the University of New Orleans. He received an LEH documentary film grant to fund production of Streetcar Stories in 1995. The film is a production of the New Orleans Streetcar Museum Project and WYES-TV. It was produced by Mizell-Nelson and directed by Matt Martinez. Peggy Scott Laborde served as production coordinator and script consultant for WYES-TV. For information on ordering copies, visit www.streetcarstories.org. Mizell-Nelson also helped create New Orleans Historical, a web and mobile platform that features scholarship and self-guided tours of metro New Orleans.