Latest

Suddenly Less Summer

How air conditioning transformed the South

Published: June 23, 2015

Last Updated: August 29, 2018

Editor’s Note: In 2015, the Madisonville branch of the St. Tammany Parish Library hosted an LEH-funded reading and discussion series titled “Suddenly Less Summer” on the transformative effects of air conditioning in the South and how the invention of climate control altered lifestyles and community interaction. Dr. Raymond Arsenault, a historian and academic from Florida, spoke at the first session and offered these thoughts on the subject. Participants shared their memories of life before air conditioning and video of their oral histories are shared here.

In truth, air conditioning is at least partly a southern invention. The age of air-conditioning, in the broadest sense, began in Florida in the 1830s when an Apalachicola physician named John Gorrie attempted to lower the body temperatures of malaria and yellow fever victims by blowing forced air over buckets of ice suspended from the ceiling. This medical experiment yielded mixed results but left Gorrie obsessed with the healing potential of chilled air. His use of a steam-driven compressor to cool air led to an 1851 patent for the first ice-making machine.

In the late 1860s, the invention of the refrigerated tank car revolutionized the meat-packing industry and spurred new interest in the science of temperature control. A number of inventors, including several Southerners, set out to prove that a technology capable of preserving dead animals could be used for other purposes, including the cooling of live humans.

To tame the southern climate, it would take more then fans and blocks of ice; it would take a true “air conditioner” — a machine that would simultaneously cool, circulate, dehumidify and cleanse the air. The first such machine was invented in 1902 by a New Yorker, Willis Haviland Carrier, but most of the new technology’s early applications took place in the South, thanks to the efforts of two Southern textile engineers, Stewart Cramer and I. H. Hardeman. Cramer, who actually coined the term “air conditioning” in 1906 when they adapted Carrier’s invention as a means of controlling the moisture content in sensitive cotton and rayon fibers. By the end of the World War I, air-conditioning as a quality-control device had spread to Southern tobacco warehouses, paper mills, breweries and bakeries.

In the South, as elsewhere, the 1920s brought the age of “comfort cooling” primarily in theaters and movie palaces, which often enticed customers with frost-covered signs boasting “20 degrees cooler inside.” The Strand Theater in Shreveport, the flagship of what would become the Saenger chain of theaters in the South, opened on July 3, 1925. Billed as the “Million Dollar Theater,” it had a 2,500-seat capacity and was air conditioned. New Orleans’ historic Saenger Theater, completed February 4, 1927, is reputed to have been the first air conditioned theater in the Crescent City. Later, in the 1930s, air conditioning slowly blew its way into an increasing number of southern banks, railway cars, hotels, government offices, hospital operating rooms, shops and even into a few homes. In southern educational institutions, even more than in hotels and hospitals, the proliferation of air conditioning was surprisingly slow. Except for a few libraries, air-conditioned university buildings were rare until the late 1950s. Louisiana State University’s Fine Arts Building was air-conditioned by 1931, but it remained an academic oddity for decades. A similar situation prevailed in primary and secondary schools. In 1948 air conditioning was installed in three Louisiana schools as part of “a national experiment to find out how much it benefits school children.”

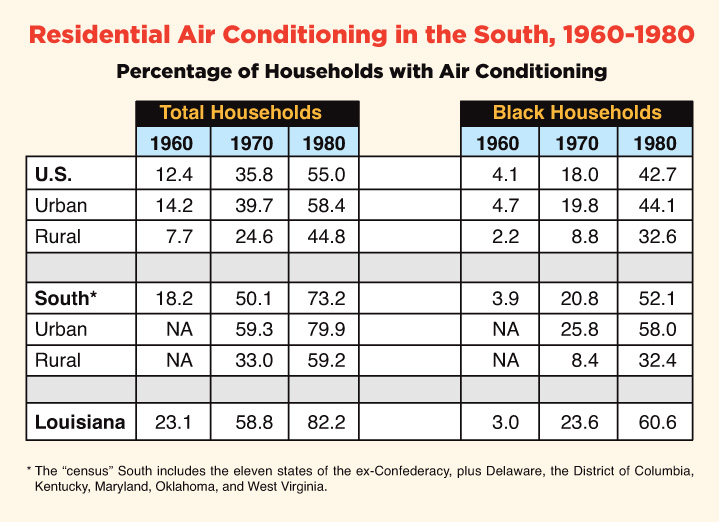

By the 1950s, the introduction of inexpensive window units and “factory air” finally made air conditioning almost commonplace in homes and automobiles. In 1951 window unit sales skyrocketed, especially in the South, and within a year the Carrier Corporation had set up model tract houses in Louisiana, Texas and Virginia in an effort to convince consumers that the air conditioner had made porches, basements, attic fans and movable windows obsolete. From the 1960s onward the development of “central air” made push-button climate control a reality for millions of southerners. The South of the 1970s could claim air-conditioned shopping malls, domed stadiums, grain elevators, chicken coops, aircrafts hangars, crane cabs, off-shore oil rigs, steel mills and restaurants. In Chalmette, Louisiana, aluminum workers were walking around with portable air conditioners strapped to their belts. As late as 1960, only 18.2 percent of southern homes were air conditioned, but by 1990 the figure had risen to more than 90 percent. What had once been a curiosity has become an immutable part of southern life and a virtual requirement for “civilized” living.

While the air-conditioning revolution has had a significant influence on almost every aspect of southern life, it has been a mixed blessing. Air conditioning has boosted the regional economy, brought personal comfort and improved health to millions of residents, and opened the region to demographic diversity, tourism and new ideas. But, on the negative side, it has taken a heavy toll on some of the more pleasant aspects of Southern life, such as the tea-sipping, porch-sitting, neighborly folk culture of open-air living.

As Southerners have retreated behind closed doors and windows into a world of whirring compressors, they have lost much of what made them distinctive and interesting, weakening that traditional sense of place and perhaps even loosening the bond between nature and humanity. As one southern gardener confessed in 1961, “We [still] enjoy gardening, but even more we enjoy being able to sit indoors comfortably and look out at our garden.” Such are the bittersweet ironies of life in the modern South.

——

Raymond Arsenault, Ph.D., is the John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History at the University of South Florida, St. Petersburg. This article was updated from its original publication in The Journal of Southern History, Vol. L, No. 4, November 1984, and Southern Exposure, Summer 1995.

Sources:

U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Census of Housing, 1960. Vol. I, States and Small Areas, Part 1: United States Summary (Washington, 1963), Tables 7, 13, 26, and 29; “Detailed Housing Characteristics,” in U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Housing: 1970. Vol. I, Housing Characteristics for States, Cities, and Counties. Part 1, United States Summary (Washington, 1972), Tables 20, 21, 27, and 37; “Detailed Housing Characteristics,” in U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Housing: 1980. Vol. I, Chapter B, Characteristics of Housing Units. Part 1, United States Summary (Washington, 1982), Tables 78, 79, 84, and 123: and ibid., Parts 2, 5, 9-12, 19-20, 22, 26, 35, 38, 42, 44-45, 48, 50, Table 64.