Sunk Coast Fallacy

Ned Randolph’s Muddy Thinking probes a legacy of extraction in South Louisiana

Published: August 29, 2025

Last Updated: December 1, 2025

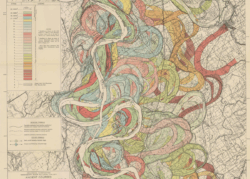

US Army Corps of Engineers, Mississippi River Commission, Harold N. Fisk. The Climate Change Law and Policy Project, LSU

When you’re crossing the threshold from outdoors to in, it’s common and polite practice to scrape your shoes across a doormat. “Don’t track that through the house!” you might be scolded otherwise.

But according to author Ned Randolph, it’s modernity, not mud, we ought to be shaking loose. In Muddy Thinking in the Mississippi River Delta, Randolph recasts mud as a necessary good, from the ancient formation of South Louisiana to the rebuilding of the state’s coast today. Modernity, on the other hand, is the trap in which we find ourselves: so isolated from nature and committed to consumption that the solutions we chase, even for reconstituting the ravaged coast, are done in partnership with the industries viewed by many to have orchestrated and then exacerbated the current mess. Modernity seems to constitute the world around us, the infrastructure of our lives. But, Randolph insists, it’s dispensable.

Much of Muddy Thinking is an account of the decisions to drain, dredge, and develop Louisiana throughout the centuries, neatly separating land and water where they once were one. It’s not just the events Randolph is interested in but also the mental processes and politics behind them. He puts forth “extractive thinking” as friend to modernity and foe to the titular “muddy thinking.” “[Extractive] thinking has led to the plundering of vital ecosystems,” writes Randolph, “and then mitigating the harms of such practices through newly imagined methods of extraction. It attempts to invent and consume its way out of its own crisis.”

Efforts to defang the dangerous Mississippi River in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were undergirded by “an almost religious belief in science that would reveal the laws of the river’s mechanics and put it to work for men.” Randolph attaches to each invention a need for man to control nature and profit from its domesticity. To wit: in New Orleans, Randolph notes, “draining the old swamps triggered an early twentieth-century real estate boom that saw a 700 percent increase in the city’s urban acreage and an 80 percent increase in assessed valuations during the same period.”

If we learn to consume less, we may depart from centuries of extraction and bloated appetites and regain the ability to make truly radical decisions about how we live, particularly in the throes of a climate crisis.

Relentless extraction comes with consequences and victims, too. Randolph’s misunderstood hero, Mud, is “anathema to the modern project of categorization and enclosure.” He draws affecting parallels between the subjugation of the Mississippi, the enslaved men and women on whom the lucrative plantation economy relied, and today’s fenceline communities, where homes are now quietly rezoned from “residential” to “residential/industrial.”

These are not new issues in which Randolph is wading. The culpability of the oil and gas industry in the state’s disasters and land loss has been hashed out in courtrooms for more than half a century, in some cases resulting in the funding of much-needed coastal restoration projects and the Coastal Master Plan. Louisiana has learned to advocate for itself to the federal government by touting the “working coast” as critical to the country’s energy supply. To Randolph’s eye, this is a political position that perpetuates current practices of land protection and resource extraction while charting the state’s future and its ability to face down disasters. “In this way, the plan reproduces the conditions for its own possibility,” he writes. “It bolsters an economy that requires further interventions in the landscape, whose disappearance exposes more people and pipelines to escalating storms.”

In taking Randolph’s recommendation to think muddily instead, “we might nurture a knack for wildness that grows on its own volition despite efforts to control the narrative.” If we learn to consume less, we may depart from centuries of extraction and bloated appetites and regain the ability to make truly radical decisions about how we live, particularly in the throes of a climate crisis. Expecting technology to save us from what we’ve manufactured is only asking for the reproduction of old ills.

Lucie Monk Carter is a writer and photographer in Baton Rouge.