Historic New Orleans Collection

Suzanne Douvillier

The extraordinary life of a pioneering ballerina

Published: March 1, 2019

Last Updated: May 25, 2022

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

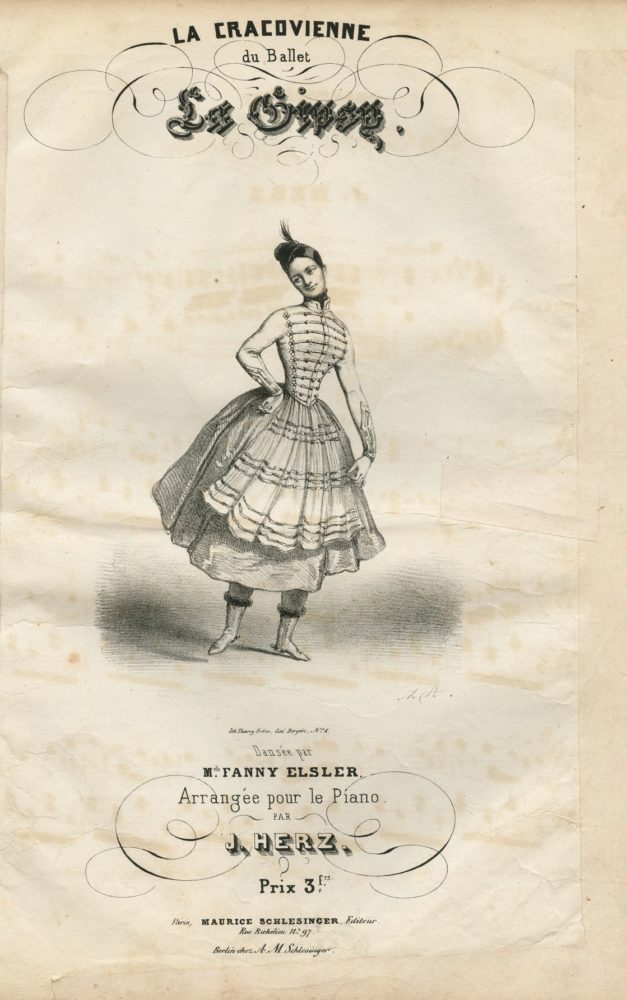

Austrian ballerina Fanny Elssler, depicted on the cover of “La Cracovienne,” from La gipsy, circa 1845.

Born in France in 1778 as Suzanne Theodore Vaillande, she was a child prodigy, studying ballet at the Paris Opera and performing at the Comédie Française before moving to the wealthy colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti), likely with a theater troupe. There she was recruited by Alexander Placide, a performer and theater manager who offered to serve as Suzanne’s tutor and manager.

A month before the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution, Placide took Suzanne, then just thirteen years old, to the United States, where she was introduced to American audiences as Madame Placide, though they were never legally married. The duo performed in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia over the next couple of years, establishing her reputation as an exquisitely graceful dancer and emotive performer.

A sojourn in Charleston, South Carolina, introduced the couple to impresario Jean Baptiste Francisqui—himself a refugee of the Haitian Revolution—and a handsome young singer and actor named Louis Douvillier. By 1796 Douvillier had won Suzanne’s affections; the two married and, in 1799, joined Francisqui in his new home, New Orleans.

At the time of their arrival, Louisiana was a Spanish colony, but the city’s performing arts were decidedly French. The turn of the nineteenth century marked the beginning of American exposure to French opera—led, in large part, by performers who had fled the revolution in Saint-Domingue. At the time, ballet was intrinsically linked to opera. It was not yet a celebrated stage art of its own, existing primarily as entr’actes and divertissements—dance interludes between or within acts—that were typically heavy on pantomime and comedy.

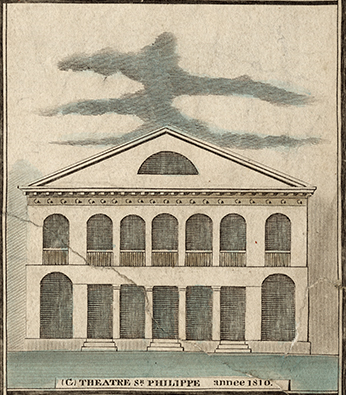

St. Philip Theater, from Plan of the City and Suburbs of New Orleans (detail) 1825; engraving with watercolor by Jacques Tanesse, surveyor. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Shortly after Francisqui’s arrival in New Orleans, he founded the city’s first opera-ballet, directing both the opera troupe and the dance corps, which included the Douvilliers, from 1800 to 1803. They performed at the city’s first theater, the St. Peter, which was built in 1792 on St. Peter Street between Royal and Bourbon. After the theater was shuttered because of poor construction and illegal gambling, Louis Douvillier became manager of the newly constructed St. Philip Street Theatre and recruited Francisqui to become its ballet master. Called “vast and grandiose” by one observer, the St. Philip cost one hundred thousand dollars—roughly two million dollars today—and could seat up to seven hundred in a city whose population was only about seventeen thousand, a third of whom were enslaved. After just four months, the theater went bankrupt, and Francisqui left the city. Louis’ career was in ruins, and so was his marriage—owing, historians believe, to his philandering. He and Suzanne separated around this time, circa 1808.

For Suzanne, her husband’s failure prompted a new beginning—and a bit of revenge. When the St. Philip reopened under new management, she was hired as principal dancer and ballet mistress, in charge of training and choreography. The first play she staged there was Écho et Narcisse; ou, amour et vengeance (Echo and Narcissus; or, love and vengeance). Douvillier, dancing in the theater that her estranged husband formerly managed, played the role of Vengeance.

In addition to being a renowned dancer, Douvillier is credited as being the first female choreographer in the United States. During her tenure as ballet mistress, she diversified the dancers’ repertoire and choreographed original works, such as a pas de trois in which she danced with two other women while dressed as a man, making her the first woman in the country known to perform a male role.

By 1814 Douvillier’s performing career was nearing its end. Remaining ballet mistress, she also became a set designer and painter in 1813—another first for an American woman. Occasionally, she returned to the stage, though she was loath to do so: her face had become severely disfigured by an unknown illness, prompting her to perform wearing a mask that covered from her chin up to her eyes.

Despite her successful career, Douvillier eventually fell into poverty, dying in 1826 at age forty-eight. Though she met an unfortunate end, she had, in her short life, bolstered the emerging performing arts in New Orleans and set new standards for what a woman could achieve in the theater.