Magazine

The Duke Dilemma

More than two decades after he ran for Louisiana governor, David Duke remains a thorny presence in state politics

Published: September 2, 2015

Last Updated: April 29, 2019

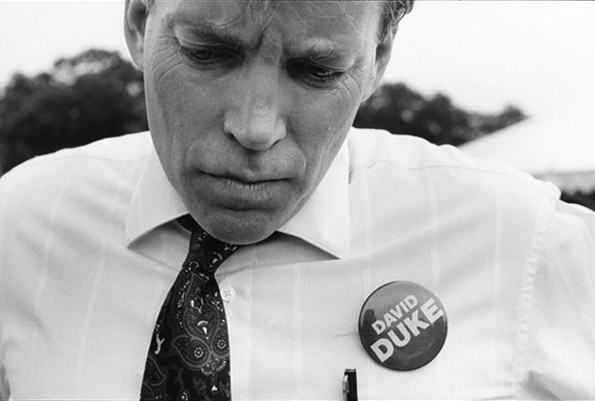

Photo by Brian Palmer

David Duke has been a candidate for state representative, governor, both houses of Congress and president. His only successful race was for a special election to the Louisiana House of Representatives where he served from 1989-1992.

The episode showed that Duke, a former state representative who made international headlines during his run for Louisiana governor in 1991, is politically radioactive now in Louisiana. That shouldn’t come as a surprise given his past record and current views. In the 1970s, Duke wore a swastika in public, served as the grand wizard of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan and today emphasizes his view that Jews are bent on the destruction of the white race. But what appears to have been forgotten is that Duke enjoyed enormous popularity among white voters during his heyday more than 25 years ago, and he was frequently accepted — and in some cases even welcomed — by the Louisiana Republican Party. A secret deal with Mike Foster in 1995 even helped usher Foster into the Governor’s Mansion.

During the 1970s and 1980s, when Duke first surfaced as a racist and anti-Semitic leader, no one could have foretold his transformation into a political hero to legions of whites in Louisiana. By late 1988, Duke appeared destined to be no more than a political crank who pined for the days of segregation and who called the Holocaust a hoax perpetrated by Jews to win political support for their causes. By then, he had lost two races for the state Senate, had left his Klan group and lost the media attention that came with it, and had even launched a third-party campaign for president in 1988 that received only a handful of votes. But just after the 1988 election, Metairie’s District 81 seat opened up in the state House.

No one paid much attention to Duke as the race began. But he was actually a skilled campaigner with years of practice in getting across his message in television and radio interviews. Duke hid his anti-Semitic beliefs from voters and instead pushed four hot-button issues. He opposed higher taxes and, speaking in racial code, attacked welfare and affirmative action and minority set-aside programs. His views resonated with voters in the 99.7 percent white district in Jefferson Parish. In February 1989 Duke narrowly defeated John Treen, the brother of former governor David Treen, by 227 votes.

A state representative from Lafayette challenged Duke’s right to take his seat, on the basis of well-documented evidence that he didn’t actually live in District 81. A majority of the House turned aside the challenge, with only three of the 18 Republicans voting not to seat him. Duke settled into his desk in a far corner of the ornate House chamber and was the only member without a seatmate.

The Republican Party caucus newsletter featured a photograph and short profile of Duke that omitted his Klan past. “He ran on a conservative platform,” it read. State Representative Emile “Peppi” Bruneau, a veteran Republican from New Orleans who chaired the Republican caucus, helped Duke draft bills and taught him parliamentary procedure. When asked why he was assisting Duke, Bruneau said that Duke was no different from any other Republican. Duke would repeatedly point to the newsletter profile and the support of Bruneau and other Republicans to blunt critics who called him an extremist. “I’m an accepted member of the Republican legislative caucus,” he would say. “They vote for my bills.”

Bruneau appeared with Duke at an April 1989 anti-tax rally at a school in Metairie. Duke was opposing a tax measure sought by Governor Buddy Roemer that would shift the tax burden from corporations to the middle-class to make the state friendlier to business. The political establishment joined Roemer in pushing for voters’ approval. Duke led the opposition, portraying himself as the defender of the little guy who was paying too much in taxes — while the government wasted money and large corporations escaped taxation. His rallies throughout the state grew in size and intensity. Voters defeated the measure, 55 percent to 45 percent. Duke’s anti-tax campaign laid the foundation for a statewide network of supporters.

Beth Rickey, a Republican activist from New Orleans, couldn’t stomach Duke. She tried to get the Louisiana Republican Party to censure him. But the effort went nowhere. The state party chairman, Billy Nungesser Sr., killed the effort, telling Rickey that it would just give Duke undue publicity. But other party leaders told her privately that attacking Duke threatened to stem the tide of pro-Duke Democrats who were switching to the Republican Party.

Rickey didn’t give up. In September 1989, she forced the Republican State Central Committee to vote on her censure motion. Only about 25 of the 140 members supported it. “To censure me would be an action against their own constituencies,” crowed Duke afterward. Rickey was furious. “I’ve been surprised over the past six months at the tacit support for Duke,” she told reporters. As she left the meeting, several state central committee members berated her for bringing up the censure motion. One man followed her to her car, accusing her of challenging Duke to win publicity and make money. Rickey tried to ignore him but finally stopped and shouted, “I don’t like Nazis! I especially don’t like them running around in the Republican Party!”

It’s important to note that Louisiana continued to have higher unemployment rates than the national average, with the state not yet having recovered from the Oil Bust of the mid-1980s. Affirmative action and minority set-asides had become popular among liberals but were blamed by unemployed working class whites for their plight. Frustrated and aggrieved, these voters were receptive to Duke’s anti-establishment and racially-tinged message. In some ways, he was tapping into the same resentment that fueled populists in Louisiana beginning with Huey P. Long, but Duke came at it from the right.

Duke sought to further capitalize on this anger in 1990 by challenging Senator J. Bennett Johnson, who was running for a fourth term. A conservative Democrat who voted with business interests, Johnston toured the state reminding voters about the courthouses, roads and aid programs that he had brought to Louisiana. Many voters didn’t care. One weeknight in April that year, Duke spoke at the International Rice Festival Building in Crowley. An astounding 600 people showed up. “Bennett Johnson couldn’t have gotten half of that,” said Cecil Picard, the state senator who represented Crowley. Duke lost to Johnston, 54 percent to 43.5 percent, but claimed victory by winning 60 percent of the white vote.

In 1991, Duke ran for governor in a race that political analyst John Maginnis would dub “The Race from Hell.” Duke denied Governor Roemer’s bid to win re-election by shouldering him aside in the primary and making the runoff against Edwin Edwards, a Democrat who had already served three terms as governor while dodging many ethics controversies, including a 1986 acquittal on federal bribery charges. Prominent Republicans such as Roemer and former Governor Treen endorsed Edwards, saying they had to put aside their misgivings about him to defeat Duke. Edwards won the runoff, 61 percent to 39 percent, in a race that became front-page news in the New York Times. But Duke again did well among whites, garnering 55 percent of their votes.

Duke could probably have won an open seat to represent northeast Louisiana in in a 1992 Congressional election. Instead, misreading his political future, he launched a challenge against President George H. W. Bush in the Republican primaries. It did not go well. Duke never won more than 11 percent in any state primary and dropped out having lost his political aura among whites.

In 1995, Duke said he would run for governor again and participated in several early campaign forums. On a summer day that year, he held a secret meeting at the Hotel Monteleone in New Orleans with a longshot candidate named Mike Foster. They met in the Monteleone’s coffee shop, and that year’s governor’s race was the item on the menu.

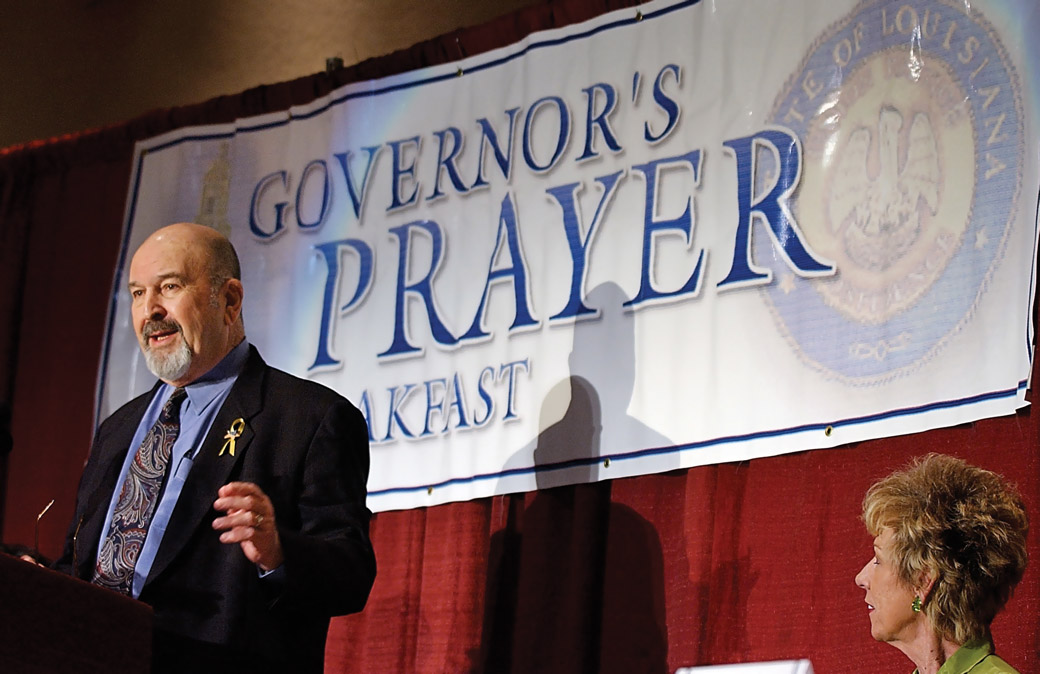

Governor Mike Foster, pictured here at a 2003 prayer breakfast with his wife, Alice, purchased a mailing list from David Duke in 1995 for $152,000. Ultimately, Foster never used the list in his campaigns. Courtesy of the Advocate, photo by Bill Feig

A two-term state senator, Foster was running but barely registered in the polls. Former Governor Roemer was the early front-runner. For this race, Roemer had shifted to the right and was campaigning as a fiscal and social conservative. Foster, though, thought he could overtake Roemer by staking out the terrain to Roemer’s right. Those voters in 1991 had belonged to Duke. And if Duke ran for governor again in 1995, Foster had no chance to be elected governor, a job his grandfather had held a century earlier. But as Foster would learn, Duke was more interested in running for the seat the following year that Senator Johnston would vacate. And he was willing to cut a deal with Foster. The deal came together when the two met later at Duke’s home in Mandeville, Foster said. He acknowledged they later met at his plantation home in Franklin and in the Governor’s Mansion.

As Duke recounted to me in 1999, he agreed to endorse Foster and quietly rally his considerable group of supporters to back Foster as well. In exchange, according to Duke, Foster promised two things: to sign a law prohibiting the use of affirmative action programs in state contracts and to refrain from condemning Duke in the 1996 Senate race. “We became friends at that point,” Duke said. “In politics,” he added, “you make certain alliances.”

Both men kept their word.

Duke backed Foster after announcing he would not run for governor in 1995, and he asked his followers to follow suit. Foster, helped by a late switch to the Republican Party and a masterful television ad campaign, rose steadily in the polls. He soon overtook Roemer, finished first in the primary and thumped Democratic state Senator Cleo Fields in the runoff by winning 63.5 percent of the vote.

Now it was Foster’s turn. After taking the governor’s office in 1996, his first order of business was signing the affirmative action ban. Duke exulted. Angry black political and civic leaders organized a big protest march in Baton Rouge. Foster didn’t back down, though, and later he rejected opportunities to denounce Duke in the 1996 Senate campaign. But Duke had lost his appeal. He finished a distant fourth in the primary with only 11.5 percent of the vote.

The 1995 Duke/Foster deal contained one other aspect that Duke kept from me when we spoke in early 1999: Foster had agreed to buy a mailing list of Duke’s supporters and contributors for $152,000. Duke went public with the sale after appearing before a federal grand jury in 1999 investigating the matter. Just like Scalise 15 years later, Foster faced a torrent of criticism. Forced to acknowledge the sale, Foster told reporters he wanted to give a “simple and straightforward” account “to make sure that the people of Louisiana can have trust in me.” Asked why he had kept the deal secret, Foster replied, ”It ain’t real cool to put out there that you are buying something from David Duke.” He added that he never used the list. But unlike Scalise 20 years later, Foster spurned the chance to condemn Duke, although, like Scalise later, he said he did not share Duke’s views on race. Several months later, the state Ethics Board fined Foster $20,000 for failing to report the payments to Duke.

It also became public in 1999 that then state Representative Woody Jenkins bought Duke’s mailing list for $82,000 for his 1996 senate campaign that he barely lost to Mary Landrieu. Harry Lee, Jefferson Parish’s Chinese-American sheriff, also disclosed that he had designs on buying Duke’s list during the 1995 governor’s race before deciding to seek re-election instead.

In 1996, Duke went back to the future by once again putting his anti-Semitic views at the forefront of his political writing and public appearances. He self-published an autobiography called The Awakening that he said he financed with the payment from Foster. In 1999, he ran for Congress and finished third with 19 percent. He founded the European-American Unity and Rights Organization, or EURO, in 2000; it was this group that Scalise addressed in 2002. In 2003, Duke pleaded guilty to tax fraud and bilking contributors by taking their money and gambling it away at Mississippi casinos. He served 15 months. Since his release, he has traveled widely in parts of Europe that have been receptive to his white-rights and anti-Semitic message.

Roy Fletcher was Foster’s media consultant in 1995 and has worked for numerous political candidates over the years. Asked to explain Duke’s decline, Fletcher said, “The world’s moved on. Duke’s issues aren’t such a big deal anymore.”

Edward Chervenak, a political science professor at the University of New Orleans, said mainstream Republicans in Louisiana have coopted many of Duke’s views, in a state that no longer has any Democrats elected to statewide office. “Affirmative action and welfare have become staples of conservative resentment against big government,” Chervenak said.

I called Duke to ask him to assess his legacy. We hadn’t spoken in nearly 20 years. He declined to speak to me — saying I hadn’t treated him fairly in the past — and then launched into a rant. “You know who owns the country,” he said. “Jews and Zionists. They are waging a war against European-Americans. They are the real racists.”

—–

Tyler Bridges freelances for The Baton Rouge Advocate and is the author of The Rise of David Duke (The University Press of Mississippi, 1994) and Bad Bet on the Bayou: The Rise of Gambling in Louisiana and the Fall of Governor Edwin Edwards (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2001).