The Dying Pelican

Romanticism, local color, and nostalgic New Orleans

Published: February 29, 2024

Last Updated: June 1, 2024

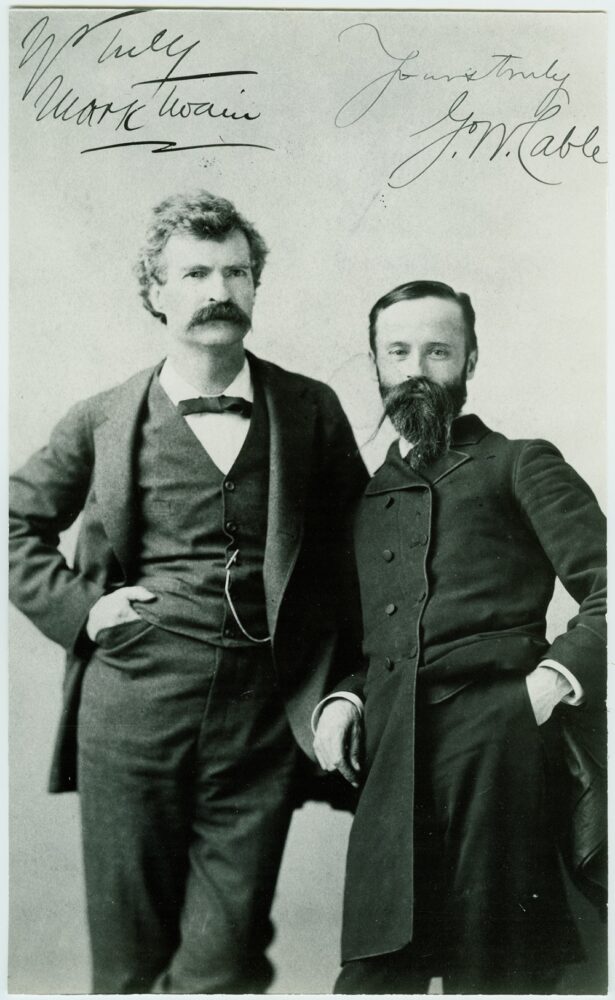

Gift of Al Rose, The Historic New Orleans Collection

George Washington Cable (right) with Mark Twain, ca. 1870.

Hearn characterizes New Orleans as a stronghold of cultural difference within a nation threatened by industrialization and homogeneity, a literary construction of the city that is heavy with British Romantic influence. With the Industrial Revolution in the late eighteenth century, Britain’s agricultural economy rapidly shifted to one oriented around machine-based manufacturing. This initial change brought with it mass print culture, imperial expansion, and urbanization as workers left agriculture for city factories: a rupture on every level of society. British Romanticism can thus be understood as an artistic backlash to the changes wrought by industrialization. The Romantics considered industrialization and its effects destructive to the natural world and the folk cultures which had (in Romantic imagining) lived peacefully alongside it. The industrial city was therefore depicted as inauthentic, a site where all things natural and instinctive were suppressed.

Economically, the city was industrializing. Culturally, it was Americanizing. And linguistically, New Orleans was anglicizing.

Some Romantic writers depicted the effects of industrialization through lamenting portrayals of its impacts—for instance, William Blake’s impoverished, lonely child laborers, lost in smog-choked cities. Others identified specific areas and historical periods as exceptional, primitive holdouts of pre-industrial life, where the emotional and ecological instincts suppressed in modern cities could thrive. These holdouts, made into vessels for Romantic nostalgia, included Medieval Europe, far-flung colonial outposts, and insular rural enclaves. These times and places were indeed culturally and linguistically distinct, less urbanized, and generally less overtly affected by industrialization, but Romantic writers identified these distinctive attributes and fetishized them to turn these sites into potent symbols of a primitive, disappearing world.

Language played an enormous role in Romantic nostalgia. Threats to linguistic diversity were considered inextricable from threats to cultural and ecological diversity. Romantic writers memorialized fading rural dialects, oral folk forms threatened by print culture, and Celtic languages. William Wordsworth pledged, in his preface to the Lyrical Ballads—itself a foundational Romantic manifesto—to convey vernacular speech, “the real language of men,” on the page. The Scotsmen Robert Burns and Walter Scott, meanwhile, both frequently wrote in the Scots dialect, an act of resistance to the ever-more dominant English language and culture. Others practiced a kind of early ethnography: James Macpherson, in a British parallel to the Grimm brothers’ project of folkloric adaptation, claimed to have unearthed and translated orally transmitted Scottish folklore.

The latter years of the nineteenth century were a period of rupture in New Orleans. Economically, the city was industrializing. Culturally, it was Americanizing. And linguistically, New Orleans was anglicizing. As these changes transformed the city, editors and readers of largely northeastern-based magazines such as Harpers embraced a newly nostalgic vision—a Romantic vision—of the lost or nearly-lost New Orleans. A crop of regionalist writers including Hearn, George Washington Cable, and Grace King helped shape this project of cultural and linguistic nostalgia. Like the locales that the Romantics elevated into symbols of the preindustrial, New Orleans was distinct for a number of reasons, most prominently in its continued use of French and the existence of a large and relatively prosperous class of mixed-race people. This reality in turn made it an ideal symbolic shorthand for an “authentic,” exotic past. In this light, the city was seen as not merely Creole and Francophone but also thoroughly exceptional.According to T. R. Johnson, professor of English at Tulane University, the seeds of this Romantic exceptionalism were planted long before the Civil War and the industrialization of New Orleans. Beginning in the late eighteenth century, New Orleans was a roaring seasonal business destination for young men from the Ohio River valley, who came south to trade in goods like whiskey and corn. These young men carried home stories of a city unlike any they knew. Beginning even then, two primary sources of fascination surrounded New Orleans: one racial and one linguistic. “People expect[ed] to see two things when they [came] down to New Orleans: people speaking French, and people who [were] neither black nor white,” Johnson said. Following the Civil War, recently returned Union troops further disseminated this discourse of New Orleans as an exceptional and exotic city, bringing it by word of mouth to audiences throughout the nation. Matthew Paul Smith points out that this regionalist literature, written by New Orleanian locals and published in national outlets, helped serve a national hunger for reunification and identity consolidation, bringing every region of the expanding United States to readers in East Coast cities.

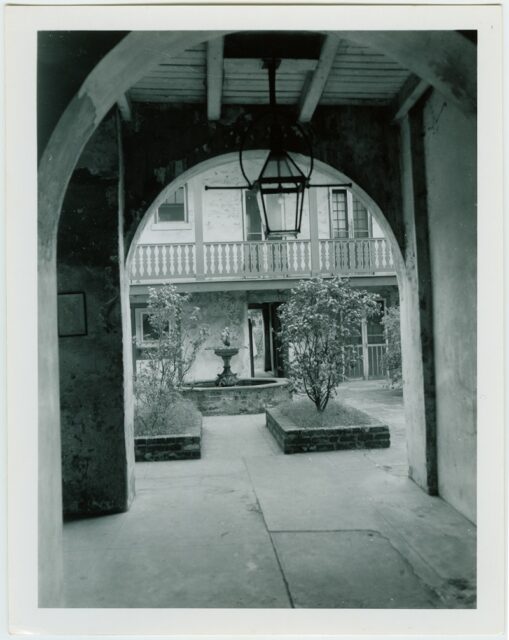

Arguably it was Lafcadio Hearn who popularized the conception of New Orleans as a symbol and an emotional state—a national vessel for displaced nostalgia, feeling, and authenticity. A Greek-born outsider who moved to New Orleans in the late 1870s, Hearn spent a decade prolifically documenting New Orleanian life with vivid ethnographic and literary sketches published in both local and national publications. In his nonfiction, Hearn tends to describe the city as more Mediterranean or European than American, and to contrast the forces of Americanization with the city’s rooted internationalism: in an 1880 essay for the City Item titled “Fire!” Hearn writes of a French Quarter crowd that “[t]here is none of the roughness which often characterizes an American crowd.” To the speech of French Quarter Creoles, Hearn attributes a certain timeless beauty and folkish grace. His City Item essay “A Creole Courtyard” describes the French Quarter courtyard as an edenic retreat from the vagaries of the industrializing, anglicizing city outside its walls, with language given as much weight as fountains and fig trees, and with Creole speech a parallel with the instinctive utterings of nature. “Without, roared the Iron Age, the angry waves of American traffic; within . . . the sound of deeply musical voices conversing in the languages of Paris and Madrid, the playful chatter of dark-haired children lisping in sweet and many-voweled Creole, and through it all, the soft, caressing coo of doves.” Hearn did not merely speak with nostalgia of Creole speech: he also took an anthropological approach, recording Creole proverbs in an ethnographic text titled Gombo Zhèbes.

Depictions of Creole New Orleans language were a shared interest among the local-color writers—and a major point of controversy. Take George Washington Cable’s historical fictions, written in the 1870s and 1880s but set in the early 1800s. These spoke to a national appetite for nostalgic depictions of southern cultural idiosyncrasy, in which dialect plays a prominent role. Working in the Romantic tradition of linguistic documentation, Cable claimed to be striving for mimesis in writing dialogue that evoked Creole New Orleanian speech—the “real language of men.” Said Smith, “Cable and Hearn see themselves as preservationists for [Creole speech]. And they recognize that it’s dying out. That gives a kind of Romantic tinge to the work—that this is a fading world that will be gone soon.” Cable blended this nostalgia with daring social critique. A white native New Orleanian, he was harshly critical of the city’s racial politics and was particularly sympathetic to the plight of mixed-race women. In his novel The Grandissimes, Cable offers up quaint depictions of colonial-era Creole New Orleans, but juxtaposes them jarringly with scenes of racial and sexual exploitation.

A French Quarter courtyard. Photo by Langston McEachern, Gift of Eric J. Brock, The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Though Cable was a native of New Orleans, the city’s old (white) guard had little fondness for him. They were as incensed by his dialect writing as they were by his unflinching depictions of antebellum oppression. Grace King, a native New Orleanian, fellow local-color writer, and conservative defender of the city’s racial order, was initially motivated to pen her own depictions of white Creole New Orleanians out of a desire to correct what she saw as Cable’s biases—in particular what she understood to be his linguistic othering of the white Creole population. According to King, Cable’s characters were scarcely able to speak English. By contrast, King’s white Creole New Orleanians spoke English sprinkled with a relatively standardized French: a marker of difference from the broader white southern upper crust, but a surface-level one, allowing them to appear ultimately American. For King, her and Cable’s diverging methods of dialect writing were inextricable from their diverging political alliances, with Cable’s dialogue making white New Orleanians appear unflatteringly primitive and undeserving. In a meeting with the editor Richard Watson Gilder, an instrumental figure in disseminating Cable’s work to northern audiences, King complained of Cable’s supposed preference for Black and mixed-race New Orleanians over white ones and proclaimed that Cable “was a native of New Orleans . . . and yet he stabbed the city in the back, as we felt, in a dastardly way to please the Northern press.”

These local-color writers correctly anticipated the decline of Creole Francophone culture. The early twentieth century saw the wealthy white Creole families who had captured the imagination of traders, soldiers, and northern readers exiting the French Quarter in significant numbers. The area became poorer and more crowded. Sicilian immigrants largely replaced the former population. But nostalgic literary depictions of Creole New Orleans continued to flower even after the near-total disappearance of that milieu. Bohemian writers from elsewhere in the United States—among them Tennessee Williams and Truman Capote—also moved into the Quarter, taking advantage of the low rent. These Anglophone writers romanticized the fallen glory of the Quarter and the city as a whole—though they were able to live in the storied Creole neighborhood precisely because the objects of their literary fascination had left it behind.

Eleanor Stern is a writer from New Orleans currently living in London. Her writing on language and literature has appeared in the New Inquiry and Bookforum.