Democracy & Media

The Garrison Tactics

The New Orleans District Attorney reveled in the spotlight, hurling accusations against his enemies and using the media to advance his investigations.

Published: August 27, 2018

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Courtesy of The Times-Picayune/NOLA.com

Jim Garrison leaves the Criminal Courts Building in New Orleans on March 14, 1967, after the first day of a preliminary hearing for Clay Shaw.

Tonight I’m going to talk to you about truth and about fairy tales. About justice and about injustice. In the months that follow you are going to learn that many of the things which some of the major news agencies have been telling you are untrue. You are going to learn that although you are citizens of the United States, information concerning the cause of the death of your president has been withheld from you. In the months to come you will learn to your own satisfaction that President Kennedy was not killed by a lone assassin. You will learn that there has been and continues to be a concerted effort to keep you from learning these facts, and you will learn, I assure you, that what I have been trying to tell you and what I am telling you tonight is true.

For the next twenty-seven minutes he positioned his investigation as a quest to the find the truth, in contrast to NBC, and other outlets whose names he mentioned, all of whom he claimed were involved in spreading the fairy tale that Lee Harvey Oswald had acted alone in murdering JFK. Garrison promised much new evidence would emerge to convince everyone that he was on the right track. He also repeatedly insisted that forces in the government and the media were in league, seeking to deceive the American people and, in the process, creating a totalitarian state which opposed his investigation because he sought, most of all, to tell the people the truth about who killed their president.

Why did a major television network agree to give this mid-level law enforcement official from Louisiana such a prominent platform? After all, Garrison was far from the first or even most prominent of the critics who had emerged in the years since the Warren Commission Report on the assassination was issued in September 1964. Garrison, like many others, became a student of that report and a voracious reader of the handful of bestselling, highly critical books written in response. In fact, conspiracy advocates and bestselling authors, including Edward Jay Epstein, Mark Lane, and Harold Weisberg, came to New Orleans and participated in aspects of the investigation Garrison had begun.

Even though they shared ideas and theories, two things distinguished Garrison from other conspiracy advocates, even the most well-known. First, as a district attorney, Garrison had the power to bring a case for conspiracy into a court of law. He had begun that process by arresting and then charging Clay Shaw with conspiracy. Shaw, a retired business executive and gay man who was mercilessly outed at the time of his arrest, was alleged to have participated in an assassination-related discussion with two co-conspirators, Lee Harvey Oswald and David Ferrie, both by then deceased. Shaw’s case remains the only alleging participation in events that led to the Kennedy assassination ever heard in an American court of law. This helps to account for Garrison’s prominence and the favorable reputation he has achieved among the conspiracy-minded community of researchers and writers since that time.

Critics suggested that Garrison’s world of “should be” sometimes overtook his dedication to dealing with the facts as they were.

Second, Garrison had a keen understanding of how the media worked. Long before he began to look into the assassination, Garrison had become a skilled practitioner of attracting attention and, in the process, driving the ensuing media coverage in directions of his choosing, even when it was critical of him. This was as true of the print media as it was of television. And, while he was very successful at garnering coverage in newspapers and magazines circulated far beyond his jurisdiction, it was television and later film that made the largest and most lasting contributions to expanding Garrison’s reach and reputation beyond Louisiana.

Some of his personal characteristics helped to accelerate his rise to prominence. Garrison relished conflict and, in the course of waging it, was very skilled at deploying colorful language and using words as weapons. He was also willing to play fast and loose with the facts. He routinely made eye-popping claims in the press, many of them thinly sourced at best. He did so for a variety of reasons: in order to keep attention focused where he wanted it, to change the subject if a storyline became negative, or to stoke popular discontent in order to achieve desired political outcomes. In his time as New Orleans DA, Garrison established a reputation as a fighter who knew how to make the media serve his purposes in the near-constant battles he joined once elected to political office. Garrison’s over-arching goal was to prevent encroachment on what he saw as the jealously-guarded prerogatives of his office and, more prosaically, to garner attention in the service of facilitating subsequent runs for higher office.

Jim Garrison surrounded by reporters on March 26, 1974, after his acquittal on charges of federal tax income evasion. The government attempted to prove that Garrison had failed to pay taxes on bribes related to a pinball gambling case. Photo courtesy of The Times-Picayune/NOLA.com

Though he was born in Iowa, Garrison spent part of his youth in New Orleans. After serving in World War II, he returned to the city and earned his law degree from Tulane. He held appointed positions with the city and state in the 1950s. He was a dark-horse candidate for District Attorney in 1961, running as part of a large field against the seventy-year-old incumbent, Richard Dowling. Forty-year-old Garrison outshone all of his opponents, including Dowling, whom he beat decisively in the runoff election. At a height of six-foot-six, Garrison struck an impressive figure, but it was his effectiveness on television that accounted, in large part, for his first victory to the DA’s office. As he wrote in his 1988 memoir:

I did not go through the streets shaking hands and slapping backs. I did not attempt to have rallies organized for me. I did not have circulars handed out in my behalf. I did not solicit the support of any political organizations. I simply spoke to people directly on television. . . . I always made it a point to appear on television alone, to emphasize my independence, to turn my lack of political support into an asset.

His telegenic qualities existed alongside a marked enthusiasm for taking on perceived opponents—both during the campaign and after his election. Four months into his first term he recommended this approach to law students at his alma mater:

If you like conflict and if you have the interest and the will to fight, and if you have a healthy hatred of scoundrels, then you can do immeasurable good as a lawyer. . . . I can tell you that nothing is more vitally needed in Louisiana and in New Orleans today than lawyers who are willing to fight for the world of ‘should be.’

As his tenure as district attorney progressed, critics suggested that Garrison’s world of “should be” sometimes overtook his dedication to dealing with the facts as they were. And, when he became embroiled in political dust-ups, as he was inclined to do, he knew exactly how to drive media coverage in directions of his choosing. In 1965, for example, Garrison’s chief investigator was accused of taking a six-hundred-dollar bribe in exchange for making sure that charges were not brought against a local bar owner accused of allowing gambling on his premises. In the voluminous press coverage that followed, Garrison used his skill with words and the power of suggestion not only to divert attention from the charges leveled against his own office, but also to suggest widespread wrongdoing on the part of his accusers.

It was television and later film that made the largest and most lasting contributions to expanding Garrison’s reach and reputation beyond Louisiana.

For example, in a letter he addressed to Mayor Victor Schiro and simultaneously provided to reporters, Garrison asserted he needed to question the mayor in order to ascertain if he was improperly colluding with the city’s Superintendent of Police, writing, “I am sure you understand that the employment of the police department, or members thereof, to accomplish a political objective is a violation of Revised Statute 14:134 (malfeasance in office).” Garrison then posed twenty-one provocative questions designed, he wrote, to help the mayor prepare for questioning on a wide array of matters by the DA’s staff. They included such suggestive queries as “8. Is it not a fact that you have been informed that a member of your staff often accepts cash gratuities? If so, what investigative steps have your initiated?” and “10. Do you have any information regarding possible alleged ‘kick backs’ in recent years with regard to parking meters for the city? If so, have you ever requested an investigation regarding this?” Like these, many of the questions suggested ongoing bribery in the mayor’s oversight of city contracts. In this instance, Schiro wisely failed to take bait and, instead, sent his own open letter to both the DA and the press, urging Garrison to investigate any concerns he might have regarding the mayor’s oversight and charge those responsible for any incidents of wrongdoing he could prove. Schiro’s tactic of pushing Garrison to provide factual support for his claims worked.

During the same imbroglio Garrison alleged improprieties, including several instances of brutality against citizens, on the part of the police. Police Superintendent Joseph Giarrusso, who had butted heads repeatedly with the DA, observed that Garrison had so successfully muddied the waters surrounding the accusations of bribe-taking in the DA’s office that no one was quite sure what was actually going on. Giarrusso described what he termed “The Garrison Tactic”:

Mr. Garrison’s tactics have been to steam roll over anyone who opposes his view. If, by chance, you are successful in opposing him, his next tactic is to threaten you. If this be unsuccessful, his final tactic is to smoke screen, call press conferences, issue press releases, and write letters. He figures, ultimately, he can out word you. Mr. Garrison is obviously not a man to disagree with because if you do, you shall feel the full force of his wrath and fury.

It was an accurate summary of how Garrison responded to critique: by putting his critic du jour on the defensive and using the press to do so. Giarrusso was also right that Garrison was very good at using language that touched the public nerve, resulting in laughter, indignation, or rising suspicion of murky forces Garrison claimed were at work against what he unfailingly characterized as his own tireless efforts to achieve just outcomes. Garrison put that tactic to good use over the years, and arguably perfected it in the years taken up with prosecuting Clay Shaw for conspiracy.

Despite his growing prominence in print and on television, Garrison often complained, colorfully, that he was the subject of unfair treatment. And the media, always looking to break news and inclined to focus on the spectacular and inflammatory, fell right into line. Even when Garrison was making questionable claims, wild accusations, or dealing in outright falsehoods, the press covered him. And, though he took some lumps in the media, on the whole Garrison brilliantly outmaneuvered all but his most persistent critics. The coverage was so ubiquitous and ever-changing that it was hard for even the most interested readers to keep up with the roster of assassination conspirators and theories the DA propounded.

Garrison (left) and Clay Shaw pass briefly outside federal court in New Orleans where Shaw sought to block Garrison’s perjury case against him. In 1969 Shaw was acquitted of charges filed by Garrison that he conspired to kill President Kennedy but two days later was charged by the district attorney with perjury. Courtesy of The Times-Picayune/NOLA.com

Garrison carefully set the stage for Shaw’s arrest, which took place at approximately 5:30 P.M., four and a half hours after Shaw voluntarily appeared in Garrison’s office. During this time, a representative of Life Magazine photographed Shaw through a two-way mirror unbeknownst to him. The hallway outside the defendant’s office on the second floor of the New Orleans Criminal Courts Building had mysteriously become congested with newsmen, photographers, television camera crews, and members of the general public. Shaw was led handcuffed into the hallway, where he was shoved and pushed through the crowd. . . . All of this appeared on television. Shaw could have been taken down in a private elevator located in Garrison’s office, but this would not have afforded the publicity Garrison was obviously seeking. Shaw’s arrest and the manner in which it was effected was outrageous and inexcusable. The only conclusion that can be drawn from Garrison’s actions is that he intentionally used the arrest for his own purposes, with complete disregard for the rights of Clay Shaw.

Within a few months of Shaw’s arrest, print and television stories emerged that were critical of Garrison’s investigation and the tactics being used to generate testimony against Shaw. In June 1967 NBC ran an hour-long special sharply critical of Garrison’s claims and the methods used by his investigators. The special featured several witnesses who claimed to have been offered bribes in exchange for providing testimony damaging to Shaw.

Shortly after the special aired, Garrison wrote a blistering complaint to the Federal Communications Commission demanding equal time to make a statement in response. And, despite his near-constant claims of a federal conspiracy to shut down his investigation, the FCC, a federal agency, ruled that NBC should give Garrison time to answer the charges. NBC complied, and Garrison’s half-hour statement was broadcast to a national audience. Despite not offering much hard evidence to ground his claims, Garrison gave a solid television performance, and many found him personally persuasive, even if the wide-ranging conspiracy he alleged was fuzzy in its particulars.

During the two years between Shaw’s arrest and 1969 trial, Garrison became an ever-more prominent television personality, even appearing, in a contentious interview, on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson in early 1968. Despite Garrison’s growing celebrity, the legal case against Shaw floundered. Part of the problem was that, at trial, the prosecution spent the bulk of their effort trying the conclusions of the Warren Commission rather than the defendant himself. The central task of convincing the jury that Shaw himself was a co-conspirator in events that led to the assassination fell short. After more than a month of testimony, a twelve-man jury unanimously deemed Shaw not guilty. Their deliberations took just under an hour.

Unwilling to accept the jury’s verdict and preferring, instead, to use the power of his office to continue in his quest to create the world of “should be,” seventy-two hours after the verdict came down, Garrison re-arrested and re-charged Shaw, this time with perjury related to testimony he gave in his own defense. That case went on for two more years, until Judge Christenberry’s 1971 ruling put a permanent injunction on further prosecution of Shaw by Garrison’s office in matters related to the assassination. In addition to eviscerating the factual basis upon which Garrison had charged Shaw in the first place, Christenberry asserted that Garrison also had a demonstrable financial stake in keeping Shaw tied up in the courts, noting that Shaw’s continued prosecution provided publicity for Garrison’s recently published book, A Heritage of Stone. The judge also pointed out that Shaw’s prosecution had enabled Garrison to secure contracts “to write three additional books” in the future.

Garrison had pursued success as an author since the 1950s, and the judge was right that it was Shaw’s prosecution that laid the foundation for Garrison’s rising reputation as a conspiracy advocate and author. Garrison’s second book was a work of fiction, albeit one inspired by his investigation. The Star Spangled Contract revolved around the cloak-and-dagger machinations that went into planning the murder of a sitting president. Novelist Larry McMurtry began his review of the book for The New York Times with these prescient lines:

Probably Mr. Garrison belongs on television. He is as big as Columbo and Kojak put together, and in appearance he out-Perry Masons Raymond Burr. Moreover, his years as the highly visible district attorney of New Orleans equipped him not merely with the broad knowledge of criminal behavior but, more importantly, with the cynicism requisite to a major career in TV. As the D.A. in a D.A. series, it is hard to see how he could miss. As a writer, however, he misses effortlessly.

Despite negative reviews of the novel, Garrison went on to publish his third book in 1988. Although much of the material in On the Trail of Assassins: One Man’s Quest to Solve the Murder of President Kennedy was a re-hashing of claims he had made in Heritage of Stone, his third book was better written and more effectively shaped and argued. Two decades after the events had taken place, Garrison took enormous liberties with chronology as he re-constructed the story of his investigation in a way that put his arguments and evidence to best advantage. In essence, he retired his case and admitted as much in the book’s introduction, writing “that history has a way of changing verdicts.” So do authors. Though the book is classed as nonfiction, careful students of Garrison’s investigation would classify the book as extremely creative nonfiction. In some places, in fact, the book completely elides the line between fact and fiction (or what some today might call “alternative facts”).

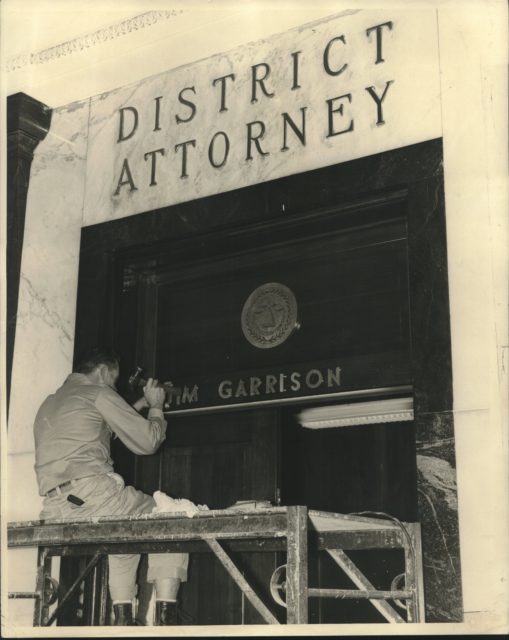

Custodian working outside the office of District Attorney Jim Garrison. Photo courtesy of The Times-Picayune/NOLA.com

Oliver Stone’s decision to option Garrison’s book and use it, with enormous creative license of his own, as the basis for his 1991 film JFK gave additional weight to Garrison’s version of events. The film’s portrayals also solidified Shaw’s villainy and Garrison’s good-guy status to a wide audience and a new generation. In the process, Garrison became not a failed prosecutor of an alleged conspirator who was found not guilty, but the person whose heroic efforts to ask hard questions provided the key that sprung the locks on all those federal secrets the media had kept and documents the government had concealed.

Garrison’s success lay in his skill with words and his success in the media. While he did not enjoy the ease of contemporary platforms like Twitter, Garrison’s understanding of the media of his day facilitated his rise to prominence. Even when press and television outlets judged his assertions dubious, they covered him, and his outrageous assertions, on a near-continuous basis, privileging their audience’s appetite for spectacle over any sense of obligation to provide fact-based coverage, even as this spectacle was being deployed as a tool for Garrison’s personal empowerment. Skillful television performances also helped Garrison’s cause, making him one of the first “reality TV” politicians in the nation. By staying on the offense in a predictably colorful manner, Garrison skillfully used the media to dampen critique. And when he was criticized, Garrison gave at least as good as he got, disparaging those who opposed him as untruthful, craven, and enmeshed in deep and systemic corruption. Garrison’s example and his currently rosy historical reputation are cautionary tales. Facts are stubborn things, but they do not stand, or stay standing, of their own accord.

Alecia P. Long is the John L. Loos and Paul W. and Nancy Murrill Professor of History at Louisiana State University and the author of The Great Southern Babylon: Sex, Race, and Respectability in New Orleans: 1865-1920 (2004). Her current project connects Jim Garrison’s prosecution of Clay Shaw’s on charges that he conspired to kill JFK to its overlooked role in the national movement for gay civil rights.

This article is part of the “Democracy and the Informed Citizen” Initiative, administered by the Federation of State Humanities Councils. The initiative seeks to deepen the public’s knowledge and appreciation of the vital connections between democracy, the humanities, journalism, and an informed citizenry. The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities thanks The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for their generous support of this initiative and the Pulitzer Prizes for their partnership.