Magazine

The King of Royal Street

W.G. Tebault and the poetry of furniture

Published: December 14, 2015

Last Updated: April 29, 2019

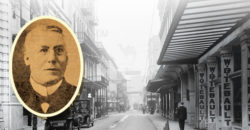

Inset: Louisiana State Museum. Right: Courtesy Library of Congress.

Inset: Portrait of W.G. Tebault. Right: W. G. Tebault's furniture store was located opposite the Hotel Monteleone on Royal Street in the French Quarter.

Tebault additionally owned the Phoenix Furniture Store at 214–220 Camp Street and the Gulf City Mattress Manufacturing Company. While known as the “King of Royal Street,” and also a director of Hibernia Bank and D. H. Holmes Company, he was as well regarded for his civic mindedness and philanthropic contributions as for his business success. Tebault was especially instrumental in forming a committee that appealed to the U.S. government for assistance in combatting a virulent epidemic of yellow fever in 1904.

Born in Donaldsonville in 1859, Tebault moved to New Orleans with his parents. The story of his fortuitous rise is fully documented in a Daily Picayune article of July 6, 1902, titled, “Luck in Business Life Illustrated by Tebault in Some Stories of His Bold Start as a Merchant on His Own Account.”

He started his furniture firm in 1878 while the city was under quarantine due to yellow fever. “Business was deader than Hector and there was nothing moving,” Tebault explained, quickly attributing his early success to providence. “The best business story I ever knew would not have happened had it not been for piece of luck.” Tebault recounted the following about his first day of business:

“To be exact, the day was October 8 [1878]. I had been talking about going into business for myself and I had taken a few preliminary steps. In fact I had ordered a few goods, and although I had no intention of leaving my employer on that particular day, yet the opportunity came unexpectedly. I was cashier for the [furniture] firm of McCracken & Brewster and they were located on this very site [Royal and Bienville]. Some trivial matter came up that displeased me and handing my keys to Mr. McCracken, I told him I would quit. He demurred, but I insisted that it would be robbery for me to remain and draw my salary when there was no business, so I picked up and walked out.

“Going down Royal Street three or four doors I took out the key to the building which I was going to occupy with a store and opened the door. The moment I did so a heavy dray lumbered up to the banquette with a parlor set and one table, which I had ordered from New York and which should have been in weeks before. I had no more thought of their arrival on that day than anything in the world … I had the driver carry the pieces up to the top floor and I was in business for myself, with only one parlor set and a table for a stock.”

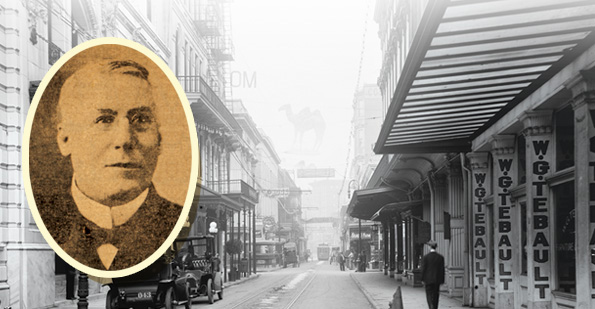

Wareroom of the W. G. Tebault furniture store.

Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans collection, 77-224-pl

As Tebault recalled, on that fortuitous day a local drayman and his wife purchased all of the pieces for $160.

Barely able to keep the new business afloat, Tebault owed his early financial survival to Mr. Obregon, a merchant from Tampico, Mexico:

“A few weeks had passed since my first day and my first business luck. The quarantines were still holding business down and it was difficult to trade. I had a very small stock of goods. The whole house did not amount to more than $2000 or $3000. But I had scattered it all over the building and had some on every floor.

“One morning a man turned in from off the street, a typical Mexican in appearance and he greeted me as ‘George,’ and was familiar. ‘I hear that you are a bright young man and have a promising business career, but that you have no stock,’ were his words … In a moment I found out that he was Mr. B. Obregon, a wealthy merchant from Tampico, Mexico and that he visited to purchase about $25,000 worth of furniture. My whole stock, samples and everything would not amount to $3000 … I took Mr. Obregon up to the roof. It was the best talk of my life—the one I have the Mexican merchant prince … I asked him how much time he would give me, and he said one month; that the schooners would be in the river in that time to load for Tampico …

“The next morning we went to breakfast together down at Chaplain’s … I had spent the night working, planning, scheming how I could get $25,000 worth of goods in one month, without a dollar’s capital and without any stock … When it came down to the cold situation I could feel the drops of perspiration stand out on my forehead. I was a youth barely 20 years of age and did not look to be more than 15 … Before I left him he had written me out his draft drawn on the Avendano Bros. for $15,000 … With that I started in to buy goods. I placed orders in every conceivable spot. … Mr. Obregon’s schooners did not arrive as soon as he expected. It was three months before he was ready to load and in that time I had won. The goods were here.”

Though late in the 19th century, Tebault’s experience speaks to an ongoing trade from New Orleans across the Gulf of Mexico and the marketability of American goods in the Yucatán.

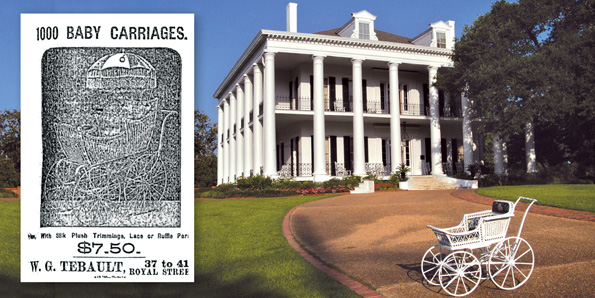

Usually not labeled, objects sold by Tebault are generally unidentifiable. However a suite belonging to the Louisiana State Museum and including an armoire, chest of drawers and half-tester bed, is stenciled “T. New Orleans LA”; it is believed to have been sold in his wareroom. At least one sort of commonplace object that Tebault offered — a white wicker pram — is found in the collection of Dunleith antebellum mansion in Natchez, Mississippi. This baby carriage precisely matches that appearing in an 1896 Tebault advertisement for “1,000 Baby carriages with Silk Plush Trimmings, Lace or Ruffle Parasols,” though it has long since lost its parasol.

Tebault’s legacy is best preserved via his remarkable series of newspaper advertisements published between 1878 and 1910. Comprised of poetry, wise maxims, romance advice and occasional political jabs, Tebault’s notices emphasized competitive prices, repeatedly proclaiming his firm “the cheapest furniture house in the South.” Boldly acknowledging this practice, one ad of 1902 is headlined, “Does Advertising Pay?” It further states:

“Advertising certainly pays. That is, the right kind of advertising pays. When we first engaged in business we bought an entire column from each of the local newspapers, and the name W. G. Tebault, furniture dealer was soon known to the public … The advertising still continues and many of my competitors who never advertised have fallen by the wayside.”

Tebault unabashedly emphasized his low prices with ads that described his goods and included their worth as compared with his own wholesale prices. A golden oak sideboard with “swell front” and French bevel mirror was described as worth $16.50, while on offer at Tebault’s for only $10. The modernity of Tebault’s electrified wareroom and the objects therein, with their sleek and hygienic qualities, were also a part of his sales pitch:

“ELECTRICITY. Tebault’s stores in Camp and Royal streets are filled with Electricity. You will be surprised at the pleasurable sensations you will receive in these stores. Your whole system will be toned up by his low prices … Just think of a man from the country buying a four-posted antiquated bed, a refuge for all kinds of vermin, with a tester on it to keep the sunlight out, and paying Six Dollars ($6.00) wholesale, when he can buy a bed made of iron, clean, neatly painted any color, for Three Dollars ($3.00).”

Wareroom of the W. G. Tebault furniture store. A white wicker pram in the collection of the Dunleith antebellum mansion in Natchez, Mississippi, appears to be one of thousands in the inventory of W. G. Tebault. Courtesy of Cybèle T. Gontar

Occasionally, these notices enumerating prices included cartoons designed to grab the reader’s attention. Far more memorable than those images, however, are some of the poems and maxims that comprised the advertisements. While the author of these lines cannot be proven, it was likely the proprietor himself—he is known to have written a play and had an impressive library. Often, these saccharine verses were designed to appeal to young couples who were setting up a household for the first time. The seven-stanza marriage proposal, “Not What She Wanted,” which appeared in the Daily Picayune in 1891, ended with the statement, “I’ll marry you, dear, if you’ll buy me a suit of Tebault’s Furniture.”

“Business,” is how Tebault titles another Daily Picayune ad of 1902. It states, “If a girl is in love it is her business; If a man is in love, it is his business; If they are going to get married it is nobody’s business; But if they buy their furniture from anybody but Tebault, it is bad business.”

Despite his great success, Tebault’s business endured the hardship of two fires. On June 26, 1884, a fire that began at McCracken and Brewster spread to adjoining buildings on Royal Street, including Tebault’s, resulting in $125,000 in damages. Again on January 7, 1908, Tebault’s Royal Street store, located in the so-called “Furniture Row,” became engulfed in flames. Once located across the street from the Hotel Monteleone, today no trace of the business remains. A plaque that once commemorated the site has since disappeared.

The day after Tebault’s death on November 30, 1924, a lengthy obituary appeared in the Times-Picayune: “Philanthropist ‘King of Royal Street’ is Dead” and included his portrait and a detailed account of his life’s work.

—–

Cybèle T. Gontar is a Ph.D. candidate in American art at The Graduate Center, City University of New York. She is currently completing her dissertation on Paris-trained New Orleans portraitist Jacques Guillaume-Lucien Amans (1801-1888). She recently opened The Degas Gallery, located at 604 Julia Street in New Orleans. Visit thedegasgallery.com.