Summer 2018

The Last Great Medicine Show

Dudley LeBlanc’s Hadacol promised miracles and delivered star power

Published: May 31, 2018

Last Updated: November 2, 2020

The active ingredients listed on the back label included bioflavonoid, biotin, calcium, choline dihydrogen citrate, cobalt sulfate, copper sulfate, d-panthenol, honey, inositol, iron, magnesium sulfate, manganese, niacinamide, phosphorus, potassium iodide, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and zinc sulfate.

Louisiana quite unexpectedly found itself at the center of the patent-medicine craze in 1943 with the introduction of Hadacol, a dietary supplement developed by Dudley J. LeBlanc, a Louisiana State Senator representing Vermilion Parish. As the story goes, in 1943 LeBlanc was being treated by a doctor in New Orleans for a nagging foot injury. The physician gave LeBlanc a weekly injection of a B-vitamin elixir that, as LeBlanc claimed, cured the constant pain in his foot once and for all. Never one to miss an opportunity, LeBlanc made off with a vial of the physician’s elixir when no one was looking and set out to replicate it. Reading and researching vitamins and minerals in hundreds of medical textbooks, he eventually concocted a vile-tasting potion that he brewed in a vintage washtub, stirring the ingredients with an old wooden boat oar in the backyard of his Abbeville home. He then packaged the final product in brown bottles with colorful red, white, and blue labels. Hadacol was born.

LeBlanc had a catholic approach to ingredient selection. In one book he learned that calcium was good for pregnant women, so calcium was added. In another book he learned that a bit of magnesium would enhance the digestive process. Add magnesium to the mix. Somewhere along the line LeBlanc decided that if one vitamin was good then two were better, and both were three times as good with the addition of a few minerals. The active ingredients listed on the back label included bioflavonoid, biotin, calcium, choline dihydrogen citrate, cobalt sulfate, copper sulfate, d-panthenol, honey, inositol, iron, magnesium sulfate, manganese, niacinamide, phosphorus, potassium iodide, vitamin B1, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and zinc sulfate. Also listed was alcohol—strictly as a preservative, mind you—and diluted hydrochloric acid, which would deliver the vitamins and minerals (and, of course, the alcohol) through the body more efficiently. At 12 percent alcohol by volume, it was no wonder that Hadacol made people feel better. The recommended daily dosage for an adult was two fluid ounces. Even at 24 proof, roughly the same potency as a bottle of wine, for the residents of the many dry parishes and counties throughout Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and other southern states, Hadacol was an answered prayer.

From grassroots beginnings—thirty employees and a $2,500 loan—the business grew to more than nine hundred employees and $3 million in sales in its first year alone. Hadacol was promoted modestly at first, with LeBlanc naturally appealing to his political base. He would appear on Sunday mornings on Lafayette radio station KPEL to be interviewed in French by L.C. Melchior about his miracle medicine.

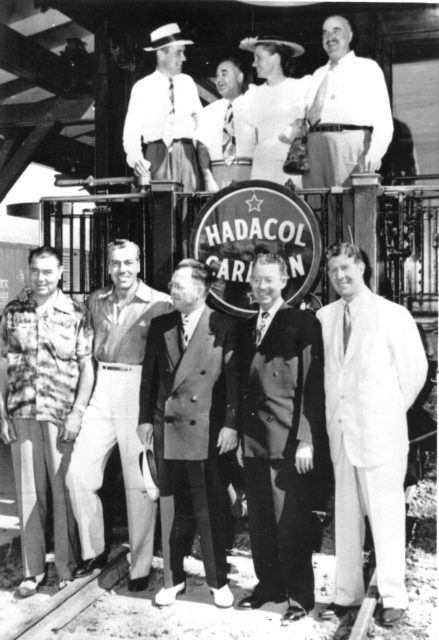

Members of the Hadacol Caravan ca. 1950. Front row: Jack Dempsey, Ceaser Remor, Railroad Superintendent TA Greison, and Rudy Vallée. Minnie Pearl is standing in center, top row. Courtesy of Lafayette Parish Clerk of Court Louis J. Perret.

Sales of Hadacol skyrocketed, overtaking a number of well-established earlier patent medicines. Among those were Kickapoo Indian Sagwa, the most popular of the “Indian” medicines and medicine shows, and the inspiration for Al Capp’s Kickapoo Joy Juice; Vermifuge, an anthelmintic whose fear-mongering ads for expelling intestinal worms and animal parasites drove sales across the rural South; Retonga Tonic, an herbal gastric tonic popular in Tennessee and neighboring states; and even the wildly popular PE-RU-NA, a nineteenth-century cure for catarrh (the so-called source of all diseases), which enjoyed a revival during Prohibition with its 18 percent alcohol by volume. In 1932, Southern Methodist University began a tradition of naming their live mascot, a black Shetland pony, Peruna in tribute to the potent elixir; the tradition continues to this day. (It is worth mentioning that, despite their unsavory reputation, not all patent medicines were sham cures. Among those that survive today are Dr. Tichenor’s, Listerine, Bayer aspirin, Milk of Magnesia, Ex-Lax, and Vicks VapoRub.)

With increased sales came increased advertising, combined with periodic planned shortages to increase demand for the product, even as LeBlanc was expanding his Lafayette factory. It seemed like Hadacol was advertising everywhere—billboards, newspapers, radio, magazines, and local pharmacies. At one point it was reported that Hadacol was second only to Coca-Cola in dollars spent on national advertising. But LeBlanc’s marketing ingenuity truly blossomed in 1950 when he developed the Hadacol Caravan—a fleet of 130 tractor-trailer trucks, each costing about twelve thousand dollars, that toured across Louisiana and neighboring states, transporting entertainers who play a series of one-night stands at ballparks, race tracks, and fair grounds, and of course delivering additional inventory to Hadacol retailers en route. You couldn’t buy your way into the show; admission was by presenting two Hadacol box tops for an adult, one box top for a child. Within a year the truck fleet grew to 175 vehicles.

Groucho Marx asked LeBlanc what the bitter-tasting Hadacol was good for. LeBlanc replied, “It was good for $5.5 million for me last year.”

The Hadacol Caravan was no run-of-the-mill minstrel show. LeBlanc spent an unheard of $75,000 per week on talent alone—roughly $3 million per month in today’s dollars. There were jugglers, clowns, strongmen, and magicians on the periphery, while onstage was an orchestra and chorus girls supporting a roster of comedians, singers, dancers, and personalities. Performers included Roy Acuff, Lucille Ball, Milton Berle, George Burns and Gracie Allen, James Cagney, Jimmy Durante, Judy Garland, Dick Haymes, Harry Houdini, Bob Hope, Carmen Miranda, Minnie Pearl, Cesar Romero, Mickey Rooney, Ernest Tubb and the Grand Ole Opry Band, Rudy Vallée, and Hank Williams. Former heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey would take to the stage to extol the virtues of Hadacol. Even novelty acts like Ted “Shorty” Evans, the British giant who topped out at nine feet and three-and-a-half inches, and who consumed fourteen eggs and twenty cups of coffee for breakfast, weighed in on the benefits of taking Hadacol every day. As was typical for that time, a separate jazz and blues show was staged for black customers. LeBlanc shelled out top dollar here as well, often featuring well-known or up-and-coming black entertainers such as “Peg Leg Sam” Jackson, Bert Williams, and T-Bone Walker.

When he wasn’t working the crowd, pressing the flesh or handing out Hadacol tokens good for twenty-five cents off per bottle, LeBlanc, with his ever-present cigar stub, would routinely appear onstage with the celebrities, one of whom would inevitably ask him where the name of the product came from. “Why did you name it Hadacol?” asked emcee Mickey Rooney.

“Well, I had-da-call it sumptin’” was LeBlanc’s reply, his thick Cajun accent providing an infectious joie de vivre and an extra measure of amusement for the crowd. This joke became as pervasive as Henny Youngman’s “Take my wife. Please.”

The real answer was that LeBlanc used the first two letters from each word in the name of his Happy Days Company, and added the L for LeBlanc. The Happy Days Company had produced an earlier patent medicine, Dixie Den Cough Syrup, as well as Happy Days Headache Powders, both of which LeBlanc agreed to stop producing in 1941 at the insistent suggestion of the Food and Drug Administration.

Dudley LeBlanc with singer Carmen Miranda. Courtesy of Lafayette Parish Clerk of Court Louis J. Perret.

No show at the Hadacol Caravan would be complete without one of the musical performers breaking into “The Hadacol Boogie,” a snappy tune written by LeBlanc and first recorded by Bill Nettles and His Dixie Blue Boys and later recorded by a number of popular artists of the day, including rocker Jerry Lee Lewis, bluesman Buddy Guy, and even the Possum Hollow Boys. Nettles’ version reached the country music Top Ten in 1949. The success of the Hadacol Caravan and “The Hadacol Boogie” inspired other musicians to jump on the bandwagon, issuing “The Hadacol Bounce” (Roy Byrd [Professor Longhair] & His Blues Jumpers), “Everybody Loves That Hadacol” (The Basin Street Six), “Drinkin’ Hadacol (Little Willie Littlefield), “Hadacol Corners” (Slim Willet), “Hadacole That’s All” (The Treniers), and “La Valse de Hadacol” (Happy & The Doctor & The Hadacol Boys).

In 1951 LeBlanc added the Hadacol Special, an entourage of seventeen plush railroad cars that he used to expand the Hadacol Caravan and his distribution network into the western states, playing a one-month stint in Los Angeles. During the fifteen-month period ending in March 1951, sales of Hadacol reached $25 million, with reported profits of $2.5 million. In a television appearance on You Bet Your Life with Groucho Marx, the mustachioed comedian asked LeBlanc what the bitter-tasting Hadacol was good for. LeBlanc replied, “It was good for $5.5 million for me last year.” Cue the laugh track and the canned applause.

Unknown to anyone except LeBlanc, Hadacol was spending more on advertising and providing high-profile talent for the Hadacol Caravan shows than the company was taking in, and LeBlanc was quick to recognize that the wild ride was over. In addition to the scrutiny of both the Internal Revenue Service and his old nemesis, the Food and Drug Administration, the Federal Trade Commission raised serious objections to the outrageous claims of Hadacol as a cure for cancer and diabetes. Realizing how the cow ate the cabbage, LeBlanc announced the sale of the company to the Maltz Cancer Foundation of New York for $8.2 million in late August of 1951, and the Hadacol Caravan, on its way east from Los Angeles, headed back to Louisiana, playing its final show in Dallas on September 17, 1951, with country music superstar Hank Williams closing the show.As it turned out, LeBlanc only received two-thirds of the sale price, because the Maltz Cancer Foundation declared bankruptcy when it found out about the $4 million in outstanding debt that Coozan Dud’s Hadacol had been carrying “off the books.” LeBlanc somehow managed to beat the devil around the stump once again by avoiding any fiduciary responsibility or liability in the transaction. And when the Food and Drug Administration finally caused Hadacol to be pulled from store shelves, it was the retailers from coast to coast who had to suffer the Hadacol hangover.

The immensely popular LeBlanc served one term as a Louisiana State Representative, one term on the Louisiana Public Service Commission, and four nonconsecutive terms as a Louisiana State Senator. He also mounted unsuccessful gubernatorial campaigns in 1932, 1944, and 1952. He died of a massive stroke on October 22, 1971, at the age of seventy-seven, just as he was planning a campaign for a fifth term in the Louisiana State Senate. With the Hadacol Caravan and the Hadacol Special, LeBlanc transformed the sometimes tawdry patent-medicine rigamarole, replete with the usual grifters, hucksters, and shills, into something truly unique in the genre. The Hadacol Caravan was an entertainment craze, a cultural phenomenon that brought the biggest names in New York, Hollywood, and Nashville to Main Street America and became the stuff of legend as the last great medicine show.

————————

S. Derby Gisclair is a sports historian and author whose next book, The Olympic Club of New Orleans, is scheduled for release by McFarland Company Publishers in spring 2018.