Geographer's Space

The Odyssey of the Greek Slave

The sculptor of a scandalous statue found a patron in an eccentric New Orleans financier

Published: September 5, 2017

Last Updated: September 5, 2019

Courtesy of the National Gallery

Hiram Powers (American, 1805 - 1873 ), The Greek Slave, model 1841-1843, carved 1846, Serravezza marble, Corcoran Collection (Gift of William Wilson Corcoran)

A case study may be found in one of the most famous sculptures of an American artist, Hiram Powers’ The Greek Slave, and it involves a colorful figure in New Orleans during one of the most contentious eras in American history.

Born to Vermont farmers in 1805, Powers honed his skills in Cincinnati and Washington, DC, and perfected them in Florence, Italy. In the early 1840s, inspired by world events and his own recurring dreams, Powers began work on a life-sized model of a young Greek woman held in bondage during the recent Greek War of Independence. Completed in clay in 1843, The Greek Slave made international news even before it was rendered in marble. That the figure was white, female, fully nude, youthfully pure in her demure pose, Christian (as made clear by a small crucifix), and not only enslaved but enslaved by Islamic “Turks” all contributed to the intense public reaction. While many viewers were provoked if not scandalized by Powers’ creation, nearly everyone deemed it a masterpiece. Galleries arranged for triumphant exhibitions, and wealthy patrons called for their own versions. Powers complied by sculpting a second model and five marble variations over the next two decades. The Greek Slave made Powers famous and helped burnish the international reputation of American art.

It was the second and third versions of The Greek Slave, made in Florence in 1846–1847, that had the greatest influence in the United States. Both versions would be exhibited in New Orleans at a time when the city neared its economic zenith—and, not unrelatedly, dominated the nation’s slave trade.

Driving much of the discourse on The Greek Slave was its New Orleans patron, the globe-trotting financier James Robb (1814–1881). Perhaps to counter his humble origins, Robb, a debonair and eccentric polymath, prided himself on his collection of fine European art. As The Greek Slave took the art world by storm, Robb in late 1845 sent a down payment to Florence for a second version of the statue—even as other patrons, including an English earl, were making the same move. What ensued was an acrimonious dispute over exactly who owned which version, and by extension, the revenues that were generated at exhibitions. Details of the controversy come to light in Tulane art historian Cybèle T. Gontar’s article “‘Robbed of His Treasure’: Hiram Powers, James Robb of New Orleans, and the Greek Slave Controversy of 1848,” published recently in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide.

Gontar recounts that Robb dispatched an agent to Philadelphia to seize what he considered to be his (i.e., the second) version of The Greek Slave and had it shipped to New Orleans. From November 1848 to March 1849, Robb displayed his treasure at his home and an adjacent gallery on what is now 121–123 St. Charles Avenue.

Despite widespread attention, Robb’s exhibition was plagued with troubles. A cholera scare suppressed attendance, as did competition from another Greek Slave (version number 3) exhibited spitefully by collaborator-turned-rival Miner K. Kellogg at the State House just a few blocks away. That Robb’s proceeds were intended to aid a local asylum also elicited rebukes, as one letter-writer—possibly Kellogg himself—saw those monies as rightfully due to Powers. Then there was that growing number of editorials in Northern newspapers—and the conspicuous silence of the Southern press—that the marble figure bespoke the moral outrage of human slavery.

National media covered the Greek Slave hullabaloo and printed indignant letters from ax-grinding stakeholders, two of whom ended up fighting a duel. Public fascination with the highbrow pomposity practically overshadowed interest in the artwork itself, and perhaps some observers of the day, like scholars today, could not help but draw parallels between the behavior of these powerful men and their treatment of women and black people. “The Greek Slave had the propensity not only to inspire passion, but also to reflect contemporary social mores,” wrote Gontar. “The same newspapers that covered Robb’s controversy also included lengthy descriptive notices for runaway slaves, [and] Robb’s seizure of his ‘slave’ property in Philadelphia and [the sculpture’s] transfer to New Orleans, where ‘she’ was displayed amidst the slave markets, is curiously parallel to the retrieval of a plantation runaway.” Indeed, both New Orleans exhibition sites were located between a cluster of slave pens around Baronne and Common Streets and auction sites in the French Quarter. Chattel slavery was also ubiquitous in the streets of New Orleans, and coffles of hired-out slaves likely marched right past The Greek Slave en route to worksites.

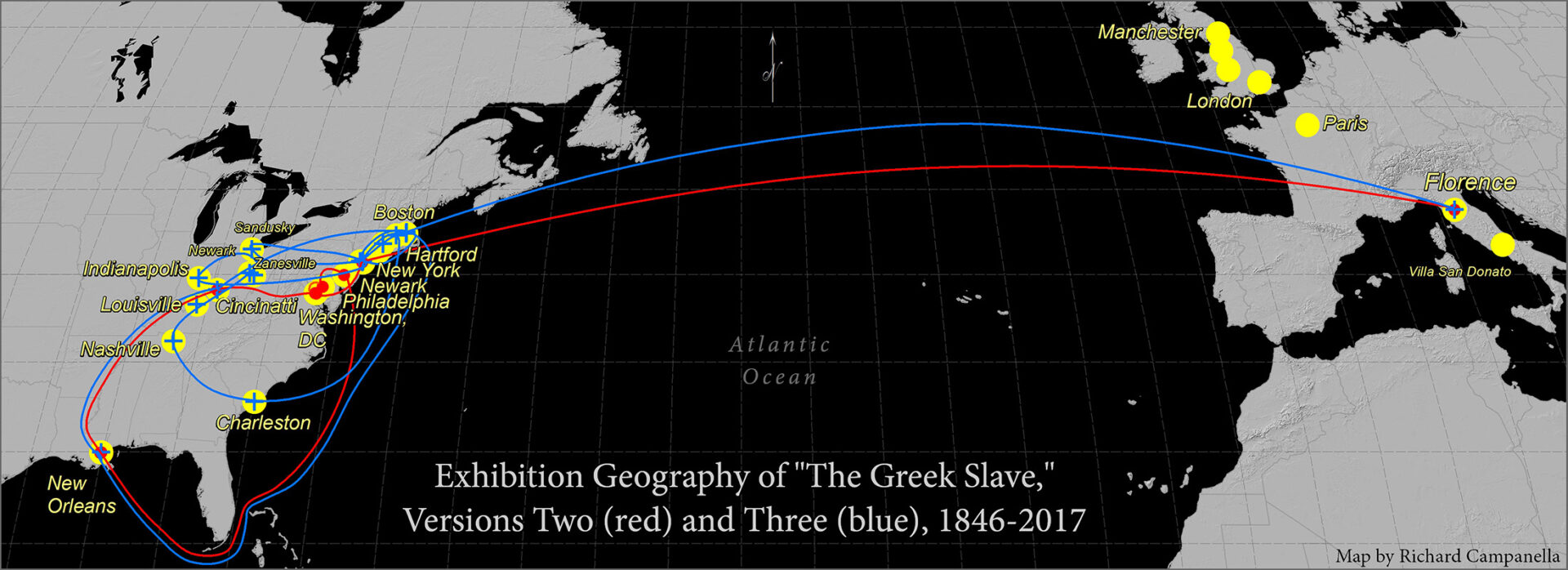

Exhibition Geography of “The Greek Slave.” Map by Richard Campanella.

Tour Geography

An article by Yale art historian Martina Droth, titled “Mapping The Greek Slave” and also published in Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide, plots the sculpture’s exhibition geography, which I have remapped here. It shows how high art circulated in this era, in a “Grand Tour” pattern, with Florence, Paris, and London playing prominent roles, followed by great American cities. There is a clear skewing toward the English-speaking world, Powers being American and the debate over slavery being particularly heated in Anglophone areas. The figures made few appearances in the Latin world, the closest exceptions being Florence and New Orleans. The pattern also reflects what geographers call “hierarchical diffusion,” in which phenomena move among population centers by their size rather than their proximity. Note how The Greek Slave began touring in the largest cities, then smaller ones, and finally towns like Zanesville and Sandusky. Cultural phenomenon as varied as sushi, gay pride, and Hamilton have spatially diffused in similarly hierarchical patterns.

As for The Greek Slave in New Orleans—two versions on exhibition, for long durations—it might seem daring to position Southern whites in empathy with the enslaved in a city so lucratively dependent on bondage. But while an anti-slavery aura circulated around The Greek Slave, tour routes were plotted primarily with an eye on revenue—and that meant large urban populations. This mostly explains its appearance in New Orleans, third largest city in American in 1840 and by far the largest in the South.

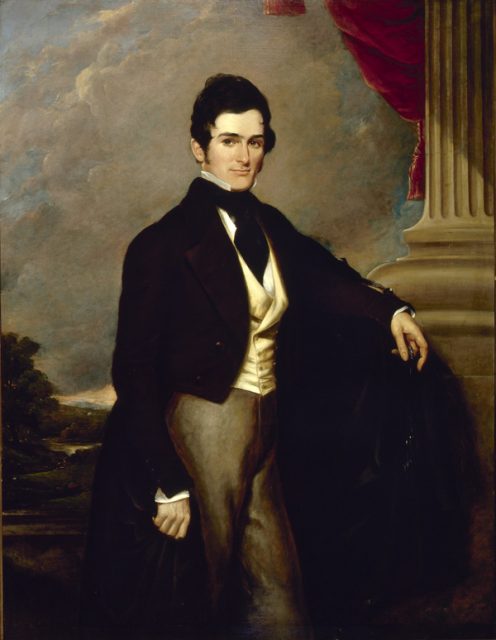

A portrait of James Robb by George A.P. Healy. Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

As for James Robb, he likely wanted to put both himself and his city “on the map” in the world of fine art. But did Robb, a Northerner by birth, also have an anti-slavery message in mind when he pursued The Greek Slave? Gontar found evidence of his investments in slaves, but also his later opposition to secession. It’s worth pointing out that Robb’s Greek Slave display on St. Charles Avenue benefited from the co-exhibition of Bartolini’s Venus financed by slave merchant and pen owner John Hagan. As for the attendees to the exhibits, it’s likely that the sculpture’s beauty, notoriety, and nudity probably drove more ticket sales than its commentary on slavery—though some patrons surely reflected on the plight of the woman in chains.

Robb’s fortunes wavered shortly thereafter, forcing him to sell The Greek Slave. But the tycoon quickly rebounded financially, and in 1852 he commissioned for an opulent Italianate palazzo to be built on Washington Avenue. “No expense was spared on finishing,” commented the Daily Picayune on the Garden District mansion; “its fresco painting was particularly superb,” and inside were “large and choice collection of oil paintings, water colors, engravings, bronzes, marble statuary, vases, and other articles of vertu.”

The economic crisis of 1857 finally did Robb in, but while he would never regain his empire, neither would he lose his pride. “My signature is not outstanding for a penny,” he declared in his elder years; “the remnant of fortune left is equal to my wants[;] my life one of tranquility, and my daily companions more precious than riches.” James Robb died in 1881 in Cincinnati, near where Hiram Powers had once honed his sculpting skills, and where Robb’s Greek Slave had been displayed thirty years earlier.

That version has been in Washington, DC, ever since William Corcoran acquired it in 1851. The Greek Slave may be seen today at the National Gallery of Art, the final stop in its long, circuitous geography.

Richard Campanella, a geographer with the Tulane School of Architecture, is the author of Bienville’s Dilemma, Geographies of New Orleans, Bourbon Street: A History, Lincoln in New Orleans and other books. He may be reached through richcampanella.com, [email protected]; or @nolacampanella on Twitter.